Anvil journal of theology and mission

Beyond measure

by Paul Bradbury

Pioneers and pioneering often feel caught in a system of measurement that is built for a different paradigm of missional ecclesiology. It’s said that “if all you have is a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail”. Current normative church metrics often feel like that hammer. Frameworks of measurement imposed without reflection on pioneers, many of whom are not using models but evolving processes to enable mission and church formation, can leave pioneers feeling like they are having to conform to the assumptions of a different system. Furthermore, these measurement frameworks that focus on the measures of mature church, such as attendance and giving, overlook more relational and transformational outcomes in the work of many pioneers. Numbers don’t tell the whole story. Often, they don’t allow space for any stories at all.

In this short article I want to explore why we are so committed to the systems of measurement that dominate church life at the moment. I am probing at the philosophical and theological assumptions that underpin the paradigm of measurement that prioritises the hard data of attendance and financial strength. Having done this, the article then makes some suggestions for a healthier approach to measurement that puts these metrics in the wider context of disclosure and evaluation.

Measurement and modernity I – growth as a higher good

In his book The Congregation in a Secular Age,[1] Andrew Root explores the challenge for church in keeping up with the culture of late modernity and its need for constant growth and acceleration. Drawing on philosophers Hartmut Rosa and Charles Taylor, Root examines religion and modernity through the lens of time. He argues that western culture has become disconnected from the moral and spiritual traditions that formed it and in so doing has become “emptied” of any sense of sacred time. Charles Taylor described the development of modernity as a move towards an “immanent frame” – that is, to a perspective on our experience that has no account of the transcendent.[2] In the same way time has become disengaged from any sense of an eternal framework, or story with a beginning and an end. Time is not moving towards any eternally held telos but reduced to an endless series of identical moments that must be freighted with all our anticipated and desired experience. Time is not held as gift within the fullness of who God is but must be acted on by us as human agents. Time is nothing more than another resource to be utilised towards our own ends.

The consequence of the utilitarian view of time is the hardwiring of growth and acceleration in modernist culture. We have become accustomed to seeing growth and acceleration as goods in and of themselves. We are nothing if we are not busy, and busier than we were before. Organisations likewise judge by virtue of their growth against past performance and that of others. The “higher goods” of growth and acceleration must then be served by the resources needed to improve them. People and money become resources subservient to these outcomes. And the church is not immune to this reality. Many churches looking to engage with the culture around them embody the values of growth and acceleration. To engage relevantly with a culture high on busyness, churches seek to be busy places too.

Root probes the “double bind” created by the logic of late modernity in which the church has become entangled. A “double bind” that means that we present churches as busy places in which growth is happening, while at the same time we find ourselves struggling to compete in a saturated market for the time and resources of our congregations to fuel continued growth.

Regarding measurement, the point is this: the system that much of the modern church is engaged in is one that prizes growth and busyness. Metrics that focus on the resources of people and money are what you would expect from a system built on these values. They are proxies for an ecclesiology dependent on growth. But is growth a “higher good” for the church?

Measurement and modernity II – the hall of mirrors

In his book The Master and His Emissary, Iain McGilchrist develops the thesis that the asymmetry of the human brain’s two hemispheres, which can be witnessed when people suffer brain injuries or strokes in one or other of these hemispheres, relates to a fundamental difference in the way these two sides of the brain “see” or attend to the world.[3] McGilchrist draws on a wealth of neuroscientific data to show how the left-hand side of the brain is associated with our ability to rationalise, theorise and codify the world. We do this to make sense of complexity and to enable ourselves to get the resources we need to survive and thrive. Meanwhile the right-hand side of the brain is associated with the ability to make connections. The right-hand side attends to the experiences it receives from the world, not by reducing to some kind of system but by holding data ambiguously and provisionally, attending to the relationships between them.

McGilchrist then goes on to argue that the power of the left-hand side of the brain can overreach itself, resisting the perspective of the right-hand side of the brain and in effect constructing the world on the basis of the world view it has created. The effect created can be described as a “hall of mirrors”, where the dominance of one particular way of seeing prevents escape from that perspective. McGilchrist provides a thorough overview of western cultural history to argue that at various points in this story, the left hemisphere perspective has taken over at the exclusion of the right hemisphere. Furthermore, he argues modernism represents just such a time in western cultural history.

This provides another important perspective on the systems of measurement that dominate in the life of the church. The measures and metrics that are offered to us are the product of the reductive processes of left-hemisphere thinking, very proficiently reducing complexity down to simple models and measurables. However, the blanket use of those metrics for every expression of church risks keeping the church in its own hall of mirrors, unable to give attention to new data, new ideas, new expressions of church that are emerging through its engagement with an ever-changing world.

Beyond measurement

So how might we find a way out of Root’s “double bind” or McGilchrist’s “hall of mirrors”? Well, let’s begin to seek an escape by probing some of the language used in this field of measurement. For example, measurement is often linked with the word evaluation – measurement and evaluation. It’s interesting to note the different perspectives these offer. “Measure” refers to a standard, the result of dividing a whole into equal parts. Applying a measure therefore means imposing a standard that has been developed in one field or context onto another, as though it were from the same system. Evaluation, however, comes from the French évaluer, which has the sense of finding the value out of something. In other words, evaluation is not imposing value, or measure, but discovering value that is being formed within something. There is therefore a sense of exploring in a much more provisional and open way in order to allow the value of something to be revealed or disclosed.

This understanding of evaluation perhaps gives us a route back, out of the “hall of mirrors” that McGilchrist describes and towards a re-emphasis on ways of giving which account for what is happening in our mission and ministry within the church that are more open and provisional. Understanding evaluation in this sense moves us toward a healthier perspective on the church as the flow of God’s mission. While Christ has inaugurated the church, the ongoing creation of the church in its time and context takes place in the wake of the movement of the missio Dei.[4]The church is constantly being created and disclosed through the work of the Holy Spirit, and part of the ministry of the church is to help discover the ongoing nature of its life.[5] This gives scope for a broader range of methods of giving account for our work, not just counting people or other resources, but bringing other methods such as qualitative research, facilitated listening, storytelling, prayer and discernment, for example.

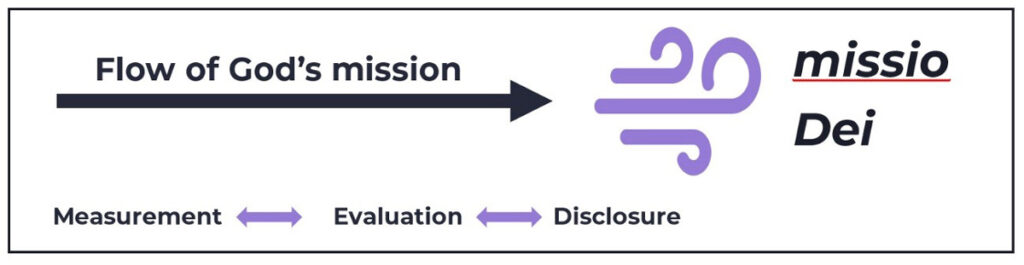

Figure 1 therefore provides a way of seeing the relationship between the mission of the church and the work of evaluation and measurement. As the ongoing form and shape of the church emerges through the work of the Holy Spirit in time and place, the first activity will be one of evaluation, not measurement. This is a process that does not impose systems or models on what is being experienced but is open to seeing the value discerned out of experience. Measurement may well form part of this process of evaluation as common patterns and forms start to emerge from evaluation. But measurement in this perspective must always serve the process of evaluation and discernment, lending more specific detail to an emerging picture.

Does this perspective get us out of Root’s “double bind”, where we are forever competing for resources to do more from already busy people? Well, Root himself recognises that the context of late modernity is one the church cannot simply escape or ignore. We have to minister in this secular age at odds with any sense of sacred time. Root urges the church not to escape into slowness as a kind of antidote to endless growth and acceleration. Instead, he invites the church to pay attention to what he calls “resonance”, which he describes as an attention to those moments of transcendence and connection that people experience in the presence of God.[6] Root invites us into the right-hemisphere perspective of an open attentiveness to the kind of things that we might recognise as authentic connections between our own experience and the presence of God. Being attentive prioritises our life as a church as a life of being in the world in relationship with God, one another and our neighbour. Being attentive to “resonance” is being attentive to what God is doing in our midst without prejudging what that activity might look like. Being attentive in this way opens us to the possibility of the new horizons of God’s saving action being disclosed to us that we might participate.

Conclusion

Moving beyond measurement is recognising the proper context of measurement. Measurement is fundamental to a culture where growth is seen as a “higher good”. Measurement is part of the furniture of a modernist culture that holds tightly to a codified view of the world. Measurement needs to find its place as a servant to disclosure and evaluation. Measurement may well have its place within the broader scope of evaluation but must not be allowed to overreach itself and construct the church in its own image. Evaluation is within the important task of joining in with the flow of the missio Dei. Evaluation will therefore use various means and methods to help the church discern what is being disclosed by God in the wake of the flow of the Spirit.

About the author

Paul Bradbury is an ordained pioneer minister in the Church of England, based in Poole, Dorset. He is the founder and leader of Poole Missional Communities, which plays host to a number of fresh expressions of church and pioneer mission initiatives. He is an associate tutor with Sarum College, CMS and Ripon College, Cuddesdon. He is currently studying for a DTh with the University of Roehampton, exploring the connections between emergence and the ecclesiology of pioneers.

More from this issue

Notes

[1] Andrew Root, The Congregation in a Secular Age (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2021).

[2] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MI: Harvard University Press, 2007).

[3] Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009).

[4] Stephen Bevans, “The Church as the Creation of the Spirit: Unpacking a Missionary Image,” Missiology: An International Review 35,

no. 1 (2007), 5–21.

[5] Clare Watkins, Disclosing Church: An Ecclesiology Learned from Conversations in Practice (London: Routledge, 2020).

[6] The word “resonance” is drawn directly from the work of Hartmut Rosa; see his Resonance: A Sociology of our Relationship to the World, trans. James Wagner(Cambridge: Polity, 2019). Rosa makes the distinction between two kinds of action in the world. The action of modernism is solely about having and it therefore reduces action to the expenditure of energy towards this cause. Rosa argues that resisting this reductive mode of action requires us to seek action that is about being in relationship with the world. For the church this advocates an “active passivity” a “hastened waiting”, which is open to the presence of God and which orients the church as a community of being more than a community of doing. See the Andrew Root books The Congregation in a Secular Age, 191–213 and Churches and the Crisis of Decline: A Hopeful Practical Ecclesiology for a Secular Age (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2022), 151–62.