How to… be a change maker

By Jane Jerrard, who spent two decades in Pakistan, working with marginalised local people to accomplish goals they never thought possible: establishing around 100 rural village primary schools, creating dozens of women’s empowerment groups and believing in a better future.

Church Mission Society believes that as we join in God’s mission through Jesus and the power of the Spirit, we see that the love of Christ renews people and places, pioneering leaders forge new paths of transformation and people on the margins flourish. As members of the CMS community we want to see lasting change – but how is it achieved? Many come and go with programmes, grants and trainings but the actual difference made can be non-existent or short-term.

How do we become change makers?

From my experience of working in Pakistan for 20 years and from my research there seem to be three important factors in transforming the lives of individuals and communities:

- change of mindset

- change of capabilities

- change of agency

In other words, change your thinking, acquire relevant skills and create an environment that provides you with increased opportunity to act.

Listening and letting others lead

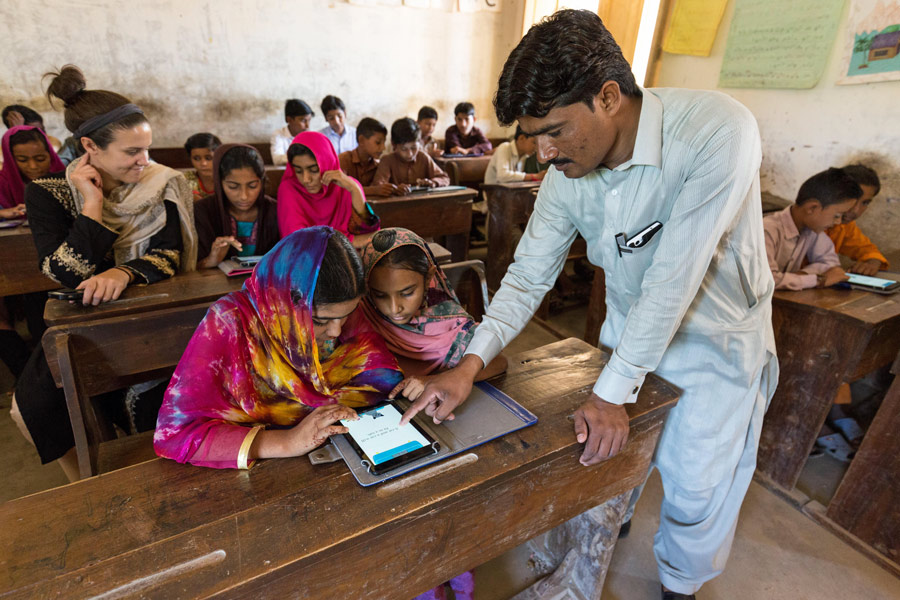

Our role in the Primary Education Project was to listen to what people wanted to achieve, support pioneers in changing mindsets, provide relevant training and facilitate them in creating an environment that would be a catalyst for change.

In the rural Sindh where I worked, low-caste Hindus had suffered generations of disempowerment and poverty; they are marginalised in society, denied and often unaware of their rights. Many work as farmers: bonded labourers with few opportunities for decision making, in debt to landlords, living with a sense of hopelessness, unable to imagine that life could be any different.

However, when individuals and communities refuse to identify themselves as victims but as change makers, when they gain relevant capabilities to achieve their goals and when they find ways to make decisions for their lives and access their rights, transformation occurs.

One man: three areas of change

For most of my years in Pakistan I worked with a low-caste Hindu man called Kanjee. He is a man of deep conviction and motivation. His parents were the only couple in his isolated village near the Indian border who agreed to send their son away so he could go to school. He lived with an uncle for his early education and in a hostel for his last two years.

As a member of a marginalised minority community, he struggled to overcome barriers due to discrimination and was determined to ensure that other members of his tribal low-caste community, particularly girls, would not experience those same barriers. I recognised that in addition to changing his mindset, he was a man taking every opportunity to change his capacity, developing his skills to be better equipped to achieve his ambitions.

He increased his agency by creating a wide network of contacts: in the media through writing articles for local newspapers and being a social activist; in civil society through becoming a member and then a local representative for the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP); with the diocese through becoming a teacher in one of their schools; with development NGOs, taking his community members to seminars which nurtured their vision and determination to provide a different future for their children, including their daughters.

Transformation spreads

Together with Kanjee, we started Village LEAP (Literacy Education Awareness Programme) with the first school opening in his village in 2001. Our vision was that these community schools should be transformative for children’s lives and that the teachers [selected from within the villages] would become agents of change to address the injustices that their communities had suffered for generations. The village teachers, observing the transformation of Kanjee’s life, began to believe that they could do the same.

At first communities found it hard to imagine that sons of farmers with limited education could become teachers, but as they observed the confidence and knowledge that their children were acquiring, they started to respect the teachers. The teachers not only taught effectively in the classroom, they also helped families with their personal problems and advocated for their village to access further government resources, especially in times of crisis, bringing flood relief and facilitating rehabilitation.

We listened to the teachers and community leaders and came to understand that the three main benefits that they wanted from their schools were cleanliness, social skills and communicative English, so we adapted our trainings to achieve these goals: personal cleanliness, so that they would no longer be perceived as ‘dirty farmers’; the ability to advocate for their rights; confidence to communicate in English, which meant government officials would listen to their case and take action to support their communities. As circumstances changed and new needs arose, a supplementary curriculum was introduced to meet these needs and to sustain community ownership of the schools. People increasingly witnessed the difference that a relevant education can make.

Transformation takes risks

Women and girls living in a rural area, as members of an ethnic minority, in an agrarian community, are regarded by UNESCO as the most disadvantaged citizens in Pakistan. Starting from Kanjee and his village, to now include 85 communities, women are developing a vision for their daughters to be enrolled in school, complete their education to college level and marry an educated man as their ‘passport’ to a better future.

For the girls in the first class of the first Village LEAP school that opened in 2001, this required strategic decisions. After four years, they realised that it would be impossible to fulfil their dreams unless they moved nearer a town since there was no accessible middle and high school in their area. Kanjee and his brother-in-law therefore motivated 15 families to uproot and create a new village near a town.

To achieve change always requires a calculated risk: the villagers owed debts to their landlord, but Kanjee judged that their contacts with HRCP and his personal relationship with a key Pakistani human rights lawyer would mean that the landlord would be reluctant to take action against them. Their accumulated government and media contacts informed them of vacant government land which they occupied; the diocese, as a Christian minority group themselves, were sympathetic to providing scholarships for these students; other contacts gave them access to government grants and support from NGOs to develop their village.

Mindset change, education and empowerment for girls

The pioneer of female empowerment in Kanjee’s village was a girl called Padma, one of his nieces. The family realised that she must complete her education to college level. Research shows that female students who have over 10 years of education and continue their education up to age 18 have more influence over the timing of their marriage and choice of partner. They also have some space for negotiated gender relations within the marital home.

After completing her basic education, Padma taught for two years in her village school, then married an educated man, used family planning, had a safe pregnancy and has a healthy child. Recognising her confidence and skills, Padma’s in-laws were willing to let her work as a teacher after marriage in a local school, a very rare occurrence in rural Sindh. She and her husband are community leaders.

As Padma expressed, “First I want to educate the children of my family and then I want to work for the people in the village…I want to show the difference between an educated daughter-in-law and an uneducated one…my first goal is to bring awareness.” And so the context is set for the next generation of change makers.

If we want to see real change, we have to be real

My previous vicar used to say, “Find out what God is doing and join in.” We tried to do that in the Primary Education Project. It took us along many unexpected paths, but as we listened, looked to God for his strength and discovered his purpose through prayer, we saw wonderful change take place.

Through working alongside the poor to bring social change, we also saw a gradual spiritual change emerging. At first there were barriers, but gradually, we of different faiths learned to respect each other, recognising our common goal to deliver quality education for our children. We learned the power of encouragement and working together as a team.

Isaiah 55:11 says, “My word that goes out from my mouth will not return to me empty, but will accomplish what I desire and achieve the purpose for which I sent it.” As trust grew and relationships deepened, Christians, Hindus and Muslims were able to sit together and engage with biblical texts. The social changes that we were able to be part of opened the way for people to experience the love and compassion of Christ and, step by step, to be transformed by listening to him speak through his written word.