Anvil journal of theology and mission

African millennial Christians in the diaspora and the identity question

by Joseph Ola

Introduction

This research-based article reflects on the implications of Christian young adults of African heritage – in the diaspora and on the continent – engaging with the question of their identity as they grow up in their multicultural contexts in an age when African Christianity is slowly taking the centre stage in world Christianity.

As an African living in the diaspora, a millennial and a Christian, the interplay of my experience of African life (growing up in Nigeria, the so-called “giant of Africa”), the unique world view I share with other (African) millennials and my core identity as a Christian has set the adventurous course of my journeys both in my migration to the UK, my exploration of pastoral ministry and my academic studies. The research upon which this article reflects, therefore, is a natural intersection of these convergent paths. Growing up in a Christian family in a semi-urban city in south-western Nigeria, I was exposed to African Christianity from a young age. By the time I was in my late teens, I began to take Christianity more personally (as opposed to it being “our family’s religion”). I was privileged to serve in various leadership positions in the Christian fellowship I was a part of while studying at Obafemi Awolowo University (between 2005 and 2010). I was a “hostel pastor” in my second year, the “Bible study coordinator” in my third year and the “fellowship pastor” in my final year. As a student who was saddled with pastoral responsibilities to fellow students, I had to stay spiritually nourished by reading Christian literature often recommended by senior colleagues to whom we looked up in the fellowship. Books by Kenneth E. Hagin, A. W. Tozer, John C. Maxwell, T. D. Jakes and Max Lucado were favourites in my growing library. By the time I began to pursue my pastoral calling more fully in the oldest classical Pentecostal denomination in Nigeria, the Apostolic Church, in 2012, the seminary of the said denomination no longer felt adequate to equip me for ministry to the younger generation I felt called to. I was convinced that an international exposure in my pastoral training would enable me to be more relevant in my ministry to the younger generation in Africa. This was the genesis of my migration to Europe in 2015 to study Pastoral Ministry in a Bible college in West Yorkshire.

My first disappointment was the realisation that the western world was not as “Christian” as I had imagined while reading books authored by westerners. (It suddenly made sense why my church in Nigeria refers to the UK as a mission field, when, in fact, the Apostolic Church itself originated in the UK in 1916.) Besides, after my one-year programme at the Bible college, I was no longer sure where I fitted in God’s mission. Indeed, I was no longer sure how to think of my identity. I had more questions than answers. I was co-opted into a new church plant that is a branch of my Nigerian church in the “UK Mission Field”. I found myself moving from a white-majority church in West Yorkshire to a Black-majority African-pioneered congregation in the north-west and began to pursue a master’s degree in Biblical and Pastoral Theology, which only seemed to amplify my identity crisis. It took a second master’s degree – this time, in African Christianity – to begin to find myself, embrace my heritage and appreciate the potential I hold to make a unique contribution to God’s mission.

Identity crisis in African Christianity

I began with my story to highlight an identity crisis that is not unique to me but rather intrinsic with the recent history of African Christianity. While the history of Christianity in Africa is almost as old as Christianity itself,1 it was not until the nineteenth century that intentional missionary activity from the West to the rest of the world as well as evangelical revivals marked a new beginning for African Christianity as it is known today. Less than 250 years later, Africa prides itself as the continent with the highest number of Christians – about 685 million2 – and arguably the continent with the most diverse expressions of Christianity.3 However, the efforts of the western missionaries that laboured on African soil in the nineteenth century became so intertwined with colonialism that describing them as “pathfinders for colonial boots”4 – as E. A. Ayandele did – became plausible. This jeopardised the preservation of the cultural identity of the Africans to whom they brought the gospel.5 The language used in describing the primal religions by the western missionaries (animism, heathenism, paganism, satanism, fetishism and so on) basically normalised the inferiority and primitiveness of the pre-Christian religious experience on the continent.6 This means that the growth and spread of Christianity in Africa in the last 120 years happened largely in the context of some “cultural disorientation” precipitated by the combination of western missionary efforts and colonialism, as many African theologians had inveighed against.7 Besides a colonial heritage, the advent of technology and globalisation continues to complicate the seeming cultural disorientation – more so for millennials who are coming to age in a world that is more connected than ever before. Globalisation continues to blur cultural lines as cross-pollination of ideas, world views and experiences continues to happen on the wheels of migration and the internet. The impact of the significant space occupied by African Christianity today, as the late British historian Andrew Walls had predicted, could be more than that of Martin Luther’s Reformation of the sixteenth century.8 It becomes important, therefore, to reassess the impact of the identity crisis that had trailed the growth and development of African Christianity in the past century, more so as it applies to millennials and the subsequent generations who will be the key players in the future of African Christianity. The research here presented attempts this.

Research overview: questions, aim, methodology and participants

Primarily, the research sought to explore the question of identity among young Nigerian Christians in the twentyfirst century by asking, “How do young Christians of Nigerian heritage (home and abroad) self-identify in light of their Christian faith and cultural heritage and what are the implications of this?” I wanted to know to what extent they stay in touch with their cultural heritage. What factors influence their Christian faith the most? To what extent is their Christian faith being influenced by western thought? How do they identify themselves with reference to their Christian faith? Do they see themselves as “African Christians” or describe themselves in other terms? I was persuaded that this line of enquiry would help me understand the peculiarities of their Christian experience both with respect to their cultural and religious heritage.

With 70 per cent of Africans being under the age of 30 and the median age of African Christians being 19.5, there is tremendous potential locked up in the youthfulness of African Christianity.

The research employed digital ethnography (using an online questionnaire) within the dual framework of both qualitative and quantitative research. The research recruited participants through an initial purposive sampling (from an online Christian mentorship platform made up predominantly of Nigerian young adults and led by the researcher), which then led to a snowballing (by asking interested participants to share the research announcement and survey link to those in their social media network who fitted the research population criteria).9

In total, 218 respondents gave consent to participate in the research,10 mostly females (64.2 per cent) with over a quarter of the 218 (26.6 per cent) living in the diaspora.11 Of these, 62.1 per cent reside in Europe, 29.3 per cent in North America, 8.6 per cent in Asia and one elsewhere. The average age of participants is 28 and they represent 16 ethnicities,12 live across 15 countries and represent at least 62 named church denominations. A typical participant is a Nigerian lady in her twenties who grew up in a religious family, currently lives in an urban town/city and is part of a Pentecostal church.

Key findings from the research

1. Findings on the African identity of the participants

In order to understand the extent to which the participants stay in touch with their cultural heritage, the questionnaire asks a few questions regarding language (fluency in spoken and written mother tongue), familiarity with indigenous proverbs and with what is considered a taboo in the respondent’s cultural background.

Table 1: Can you fluently speak your mother tongue?

| Age group | No | Yes | Grand total |

| 18–20 | 37.5% | 62.5% | 100% |

| 21–25 | 33.9% | 66.1% | 100% |

| 26–30 | 17.1% | 82.9% | 100% |

| 31–35 | 5.5% | 94.5% | 100% |

| Entire sample size | 18.3% | 81.7% | 100% |

Table 2: On a scale of 0 to 5, how well can you read works of literature written in your native language? (Showing results for 0 and 1 only)

| Age group | 0 | 1 | Grand total |

| 18–20 | 25% | 0% | 25% |

| 21–25 | 6.3% | 6.3% | 12.6% |

| 26–30 | 0% | 8.6% | 8.6% |

| 31–35 | 1.4% | 1.4% | 2.8% |

| Grand total | 32.7% | 16.3% | 49% |

| Home or diaspora | 0 | 1 | Grand total |

| Diaspora | 0% | 8.8% | 8.8% |

| Home | 0% | 3.8% | 3.8% |

| Grand total | 0% | 12.6% | 12.6% |

From Tables 1 and 2 above, it is clear that the younger the participant, the less likely they will be fluent in their indigenous language. While only 5.5 per cent of participants aged 31–35 admit to not being fluent in their indigenous language, it rose to almost 4 in 10 (37.5 per cent) among participants aged 18–20. Likewise, while only 2.8 per cent of participants aged 31–35 could not read works of literature written in their native language, it rose to 1 in 4 participants (25 per cent) among those aged 18–20. Furthermore, as the last three rows of Table 2 show, the challenge of fluency and proficiency in native language is greatly increased for participants in the diaspora. The same trend was seen with familiarity with proverbs and with what is considered a taboo in the cultural heritage of each participant.

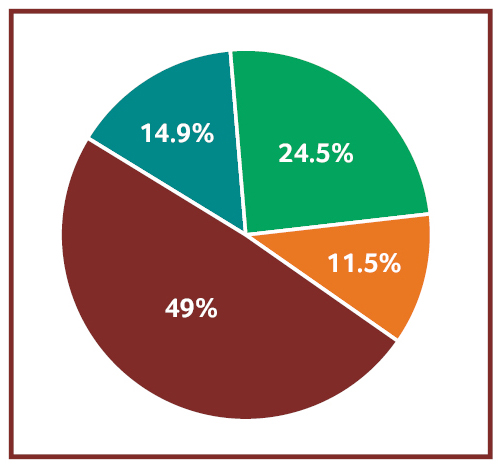

Figure 1: As an African Christian, how important is the “African identity” in your faith?

208 responses

It’s not important (11.5%)

It’s somewhat important (49%)

It’s so important that it defines my Christian faith (14.9%)

I don’t consider myself as an “African Christian” (24.5%)

Moreover, as Figure 1 reveals, while 36 per cent of all participants either do not consider themselves as an “African Christian” (24.5 per cent) or do not think their “African identity” is important to their Christian faith (11.5 per cent), the tendency is significantly higher among younger participants (57.1 per cent of 18 to 20-year-olds) as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: As an African Christian, how important is the “African identity” in your in your faith?

| Age group | “It’s not important” or “I don’t consider myself as an “African Christian” | “It’s somewhat important” or “It’s so important that it defines my Christian faith” | Grand total |

| 18–20 | 57.1% | 42.9% | 100% |

| 21–25 | 39.3% | 60.7% | 100% |

| 26–30 | 38.6% | 61.4% | 100% |

| 31–35 | 29.2% | 70.8% | 100% |

Furthermore, to probe the understanding of the participants on what “African identity” means, the questionnaire asks, “In what ways is your church ‘African’, if any?” to which a wide range of responses were received. The broad categories identified in the responses include mode of worship (the jubilant singing and dancing), leadership (the domination of male leaders), doctrine (beliefs and practices that are adaptations of African traditional religion), prayer style (loud and spirited), language (evidenced by the need for interpreters in certain denominations), dressing (especially regarding what is considered inappropriate – especially for women) and conformity to African culture and traditions (e.g. upholding the values of respect for elders, togetherness and honour for spiritual leaders as representatives of God). Generally, the tone with which many of the participants described what they considered African practices or beliefs in their church is with disdain. For example, R8, a 26-year-old male, says that in his church, their “dressing, type of songs sang, and our doctrine in the last 20 [years] has been skewed and infested” while R127, a 20-year-old female, says her church is African simply because the church is “too rigid and primitive”. Adding to the denunciations against African identity, R172 (a 21-year-old female in the diaspora) says of her African majority church:

My church denomination was founded by an African and has its headquarters in Africa. Traditions like respecting and obeying elders even when they are wrong, inability to explain myself because I am younger, [and how the pastor’s] personal conviction automatically becomes a doctrine are the African things about my church.

Such responses are not without exception, of course. Speaking proudly of her home church’s Africanness, R107 (a 35-year-old female in the diaspora) writes,

I would say my church back in Nigeria is very African in its mode of worship and leadership… [T]here are parts of the Yoruba culture reflected in the doctrines of the church [and] I do not consider this to be a disadvantage, rather, I consider it to be an expression of the diversity of the church of Christ.

In summary, while older African Millennial Christians (AMCs) can be said to be more in touch with their African heritage, younger AMCs in Nigeria are less likely and those in the diaspora even more less likely. Likewise, older AMCs significantly consider African identity as being at least somewhat important to their Christian faith while younger AMCs are less likely to do so. Finally, most AMCs are less likely to view their sense of African identity with pride; on the contrary, they are more likely to see it as being restrictive – more so for the females.

2. Findings on factors influencing the faith development of participants

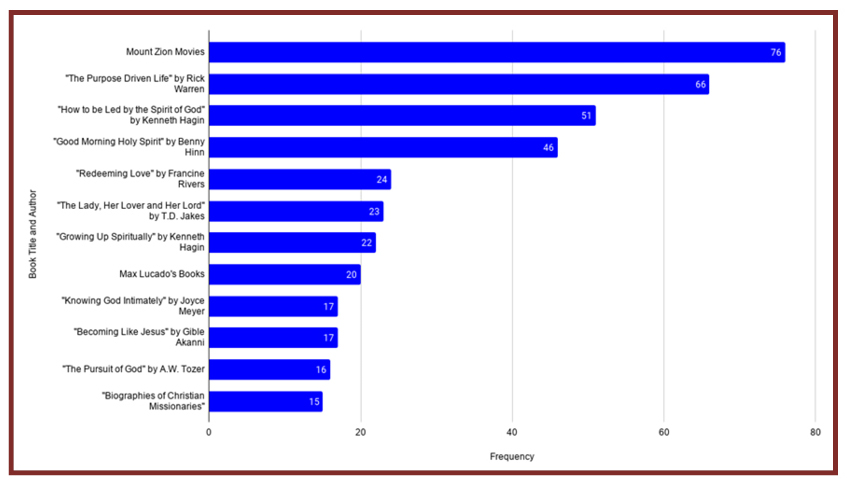

It was found that the top three factors influencing the faith development of the participants are: their parents (47.5 per cent); a Christian fellowship in a school, college or tertiary institution (35 per cent); and a Christian mentor (20.7 per cent). It was interesting to find out that the aforementioned factors have more influence on these millennials than their church pastors or the pastors they follow online (17.5 per cent and 17.1 per cent respectively). “Christian literature” also appears to be a top influence (12.9 per cent), especially among those in the diaspora. Talking more about the books that had influenced their faith development (Figure 2), the first striking thing to note is that the highest ranking “book” (supposedly) on the chart is, in fact, not a book but a Christian movie ministry based in Nigeria called “The Mount Zion Faith Ministries International” (MZFMI). The fact that the question that generated these responses in the questionnaire was open-ended led to this finding,13 as many of the respondents believed that MZFMI deserved to be mentioned as a major influence on their faith development and, as an insider to the research population, I could not agree more. MZFMI is the most successful Christian movie industry in Africa and a worthy contender on the global stage. Within the last 20 years, the ministry has partnered with drama ministries in Canada, USA, Australia the UK and other western countries to shoot movies that were intended to reach out to diaspora African Christian communities as well as their ready audience in Africa. Indeed, the story of the impact of MZFMI is a research project waiting to be investigated.

Another striking finding in this top-12 resources list is that out of the 11 authors on that list, only one is an African (and Nigerian) – Gbile Akanni. All the others, apart from Benny Hinn, are American authors and all the books specifically mentioned were published between 1946 and 2003. My insider insight suggests that these books were often recommended reading from the older generation of adults or older “young adults” who are mentoring this generation of millennial Christians.

Figure 2: The top 12 most influential books and their authors

| Title and Author | Frequency of mention |

|---|---|

| Mount Zion movies | 76 |

| The Purpose Driven Life by Rick Warren | 66 |

| How to be Led by the Spirit of God by Kenneth Hagin | 51 |

| Good Morning Holy Spirit by Benny Hinn | 46 |

| Redeeming Love by Francine Rivers | 24 |

| The Lady, Her Lover and Her Lord by T. D. Jakes | 23 |

| Growing Up Spiritually by Kenneth Hagin | 22 |

| Max Lucado’s books | 20 |

| Knowing God Intimately by Joyce Meyer | 17 |

| Becoming Like Jesus by Gbile Akanni | 17 |

| The Pursuit of God by A. W. Tozer | 16 |

| Biographies of Christian missionaries | 15 |

3. Findings on the impact of western thought on the participants

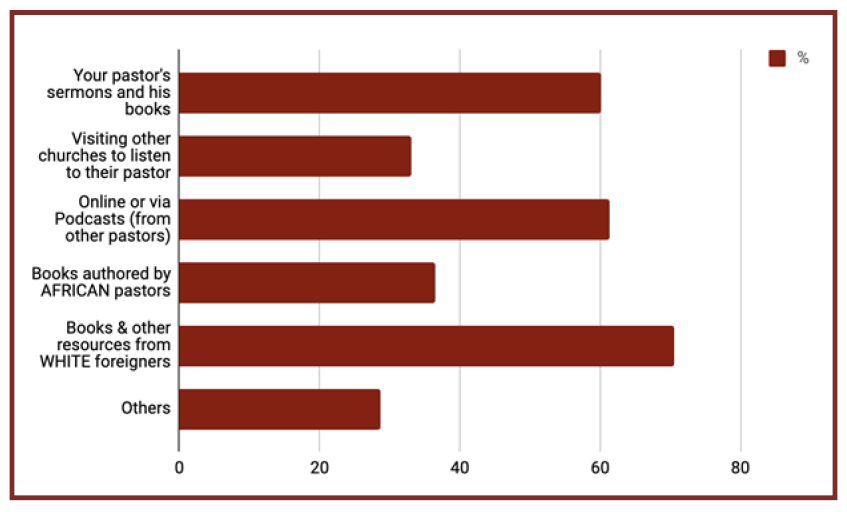

Besides the diminishing proficiency in indigenous languages alongside an increasing early mastery of English language and the dominance of western Christian authors in the faith formation of the population represented by the respondents, further findings confirm the high impact of western thought on the population. For example, participants were found to be impacted more by movies and podcasts from “whites/westerners/foreigners” than by the same resources produced by “Africans/Nigerians”. This confirms my findings in an independent research study I carried out in 2018 involving 100 African Christian youths from different church traditions between the ages of 18 and 25. I asked a few questions aimed at discovering the source of their spiritual nourishment among other variables. I found that:

Much more youths claimed to get their spiritual nourishment from engaging with books or other resources from “white foreigners” (70.5 per cent) and from online podcasts or videos (61.4 per cent) than from other African ministers (36.4 per cent) or from their pastor’s sermons or books (60.2 per cent).14

Moreover, some of the participants made remarks with undertones of the inferiority of African cultural heritage to the western world view. For example, R23 (a 26-year-old female) says, “I believe we took religion and aligned it with our culture – which is not so in the western world – and this has reduced our thinking faculty…” To R23, Africans, by virtue of their inherent religiosity, have a reasoning deficit, which, in her presumption, “is not so in the [superior] western world”. The same inclination is found in the remarks of R48 (a 22-year-old female), who says that in her church, they “pray aloud and fight against [spiritual] enemy [more] than they do abroad” – in which case, what “they do abroad” is supposed to be better – or worse, the standard. In summary, the West continues to have a dominant influence on the world view of AMCs, often to the detriment of the cultural heritage of the AMCs.

Figure 3: Where do you get your spiritual nourishment from?

Reflection on research findings and its implications

In a nutshell, the findings of this study are like a two-page letter with bad news on one page and good news on the other. The bad news is that African identity is gradually being eroded among AMCs, less gradually among those in the diaspora, and predictably more so among the upcoming generations after them. With the prevalence of the tendency to overvalue and embrace foreign (western) culture at the detriment of African traditional values, younger AMCs are further away from owning their Africanness than the older AMCs are. As AMCs are becoming parents, and soon, grandparents, one wonders how long before African identity becomes merely a label for those living in the continent so-named or a prefix to a new identity for those in the diaspora. The good news, however, is that AMCs are still very involved and interested in Christianity – unlike millennials in the West! In their research on American millennials, Thom and Jess Rainer found them to be “the least religious of any generation in modern American history”.15 Only a small portion of their over 1,000 respondents are Christians while a majority represented a post-Christian mindset – and their research is now 10 years old! By contrast, the research population for this study comprised of more than 200 Christian millennials, all of whom had committed to taking the Christian faith seriously – most of them beginning in their teenage years. The primary implication of this research finding, therefore, is a need to figure out a way to foster the discovery of a healthy selfawareness for these young Africans – a self-awareness that is rooted in their culture and heritage. An African proverb says, “If you do not know where you came from, you will not know where you are going.” In other words, as Harvey Kwiyani articulates it (quoting Marcus Garvey), “Any people who are not aware of their history and culture are like a tree that has no roots.”16 The exploration of creative means to reconnect AMCs to their heritage, thus fostering a healthy self-awareness and reclamation of their Africanness, will have implications for those influencing them, for their Christian faith and ultimately for missio Dei.

1. Implications for older AMCs

The research finding already points to a group of culturally intelligent AMCs (most of them between ages 31 and 35) who are still proficiently in touch with their African heritage and values both in Africa and in the diaspora. For example, R45 (a 31-year-old diaspora female) says:

We need to be “African Christians” not an African who is a Christian but trying to fit their Christianity into a western mould, thereby making our culture second place to our religion. One body. One flock. God placed us in our families for good reasons so we should not discard who we are in order to be who God is calling us to be.

Three out of every 10 participants in this study are in that 31–35 category. Those among them who are living in the African diaspora are already grappling with the challenges of living in the tensions of multiple cultures – me, too! This affords us more critical reflection that can potentially yield even more adeptness in our cultural intelligence and make us more suitable to pass on the legacy of a healthy self-awareness and rootedness in our African identity. Those in this category are the people with the greatest potential of ameliorating the slow death of African heritage among younger AMCs and Gen Z screenagers.17 This is so for a few reasons.

First, many of us are becoming parents and are coming to terms with the full weight of the parental responsibility coming upon us. We are in a vantage position to see the need to claim our cultural identities with their full riches so as to be able to pass them on. The finding in this research of our parents being the most influential faith development factor in our lives is striking (and consistent with the finding in similar studies).18 However, while it is almost too late for our parents to make any more significant contribution in orientating us towards a development of a healthy African identity, we now have that opportunity. In doing this, however, we must avoid making a common mistake our parents made. As an insider to the research population, I believe that part of the errors of the generation of our parents is in teaching us cultural values merely as tradition without making us see the “why”. When the true value of a cultural value is unknown, the motivation to pass it on is lost. As such, those of us who are culturally aware millennials will do well to pass on the baton with the willingness and readiness to answer the barrage of questions that our children will ask us.

Second, that millennials are looking for mentors is a known fact. “Three out of four Millennials would like a leader to come beside them and teach them leadership skills” because they “value a leader who is willing to take his or her time to teach skills that otherwise may not be learned”.19 In light of this, older AMCs – many of whom have benefitted from mentoring themselves – will do well to be more intentional in mentoring younger millennials and those coming behind them. As the pioneer of an online mentoring platform with a membership of over 3,000 AMCs located across over 60 countries, I have witnessed first-hand how desperately younger AMCs are looking for mentors and how mutually impactful, effective and transformative the experience can be for older AMCs who will be willing to take up this responsibility. Since AMCs are being influenced more by their mentors than their pastors, older AMCs will be perpetuating a good legacy by making themselves available, accessible and teachable in order for younger AMCs to learn from them in life-on-life contexts. To be effective at doing this, they will need to equip themselves with resources from around the world and, more intentionally, go after resources that can help them understand their Christian faith through the lens of their African heritage. For starters, in addition to the Kenneth Hagin books and Rick Warren’s The Purpose Driven Life, they should have the Africa Study Bible and Africa Bible Commentary on their shelves or smartphones.20 21

Third, those among the older AMCs who have (or will have) a call into pastoral ministry have a tremendous opportunity to make a difference in giving both roots and wings to the next generation of African youth. (After all, making a difference is the major definition of “success” and “achievement” among millennials.)22 They will need to pursue pastoral and theological training that will help them minister effectively in a way that prospers an African contribution to the mission of God through their ministries. One way to do this will be for them to develop proficiency in the understanding and use of African proverbs in their sermons and everyday speech. Indeed, one could ask, what will be African about the preaching of an African preacher who is neither familiar with nor appreciative of African proverbs? For the African, without proverbs, “speech flounders and falls short of its mark, whereas aided by them, communication is fleet and unerring”.23 This necessarily calls for paying attention to the personality and wisdom of the elderly in their lives. These elderly people show the AMCs images of who they will also become in some years’ time, according to their time of life. Those among the older AMCs without a specific pastoral call will do well, in any case, to plug themselves into serving in their respective churches as ambassadors of Christ and role models of proper humanness (as conceptualised in Ubuntu or Ọmọlúàbí African philosophies).24 25 An example of what this could look like is the Ọmọlúàbí Podcast I launched in 2021, co-hosted with my wife. The focus of the podcast is to highlight the convergence between African proverbs and Biblical wisdom and its dual aim is both to showcase a rich collection of African proverbs and offer such indigenous wisdom to young adults of African descent on demand – and, indeed, to anyone.26

2. Missiological implications for African churches in the diaspora and in Africa

With 70 per cent of Africans being under the age of 30 and the median age of African Christians being 19.5, there is tremendous potential locked up in the youthfulness of African Christianity.27 However, unleashing this potential depends upon a mutual involvement of the young and the old coming sideby- side in God’s mission. Joel’s prophecy about God pouring out his Spirit “upon all flesh”28 in the last days is already upon us – indeed since the day of Pentecost! – and it continues to have more pressing relevance with the passage of time. Andrew Walls’s submission of this current era of Christian history pointing to a justifiable “hope for greater things”29 is arguably truer in Africa than elsewhere. (Indeed, the shift in missiological discourses from “Kingdom” to “Spirit” seems more “at home” in Africa’s enchanted cosmology than elsewhere.)30 So while mission today excitedly looks like “finding out where the Holy Spirit is at work and joining in”,31 it is even more exciting that this Spirit is available to all flesh – young and old, male and female alike. The “spiritual experience and expertise of every member,” as Father Koshy reminded us at Edinburgh 2010 conference, “must be recognised and drawn into the common spirituality of the local congregations”.32

The Yorubas (West Africa) have a couple of helpful sayings that put this in perspective. They say, “An elder cannot be in the market and permit a child’s head to rest askew (at the back of his mother).” In other words, to be an elder is to be capable of looking out for children and covering the oversights and blind spots that threaten their safety. In some other contexts, they will say, “The youth’s hand cannot reach the rafters, and the elder’s hand cannot enter the gourd” – that is, both the young and the old have unique contributions to make if only they will work together. These two sayings find definite intersection in a third saying: “A youth is wise, and the elder is wise: that is the principle by which people go about at Ifẹ̀” (Ifẹ̀ being the cradle of all Yorubas and, in this proverb, symbolising “all of life”). The wisdom in these sayings is that both the young and the old – and indeed, male and female – have something to offer in every area of life. The youths need the mentorship of those older than them and the older generation need the creativity and fresh expressions of the youths. African Christianity needs such mutuality that recognises the relevance of both the young and the old and makes both feel welcome in a church.

Specifically among diaspora African Christians, parents need to be more intentional in deepening the heritage consciousness of their children. They can do this, as Paul Ayokunle suggests, by “demonstrating genuine appreciation and regard for the beauty of their own culture”.33 Besides, older millennials (especially those deepened their roots in Africa and are now flapping their wings in the multicultural West, having migrated there more recently) need to model their appreciation for their cultural heritage to younger folks. Likewise, African diaspora pastors will need to embrace and learn how to do church multiculturally and intergenerationally so that the younger generation will find their churches more relatable and the opportunity for expressing their heritage without inferiority will flourish. It is high time young people in their twenties were incorporated into the leadership of our churches – which, according to the research findings, must be multi-ethnic and multicultural for AMCs to belong therein. Moreover, in discipling AMCs and those coming behind them, African churches – on the continent and beyond – will need to figure out how to redeem the traditional rites of passage – especially initiation – that used to prepare young men and young women for adulthood in different African communities.34 Western education cannot suffice for such preparation. The fact that there were unchristian practices in some of these traditional rites is not sufficient ground to throw the baby out with the bath water. If there is a message that can be translated into any context, it is the Christian message. In any case, the African (diaspora) church needs both the Bible and helpful cultural values to ready her youth for what lies ahead.

Conclusion

As the team at the Center for the Study of Global Christianity tells us, “A typical Christian today is a nonwhite woman living in the global South, with lowerthan- average levels of societal safety and proper health care.”35 With Africa being home to most Christians across the world, that “non-white woman living in the global South” could very well be an African, and given Africa’s median age (18),36 she would likely be a young adult. The obvious likelihood is that sooner than later, the leaders of world Christianity will be today’s AMCs. However, one cannot but wonder, when the time comes for Africa’s youth to take the lead in global Christianity, whether they will be faithful enough to deliver a uniquely African contribution that will advance the mission of God. As Andrew Walls has occasionally reiterated, the fullness of Christ – which is our Christian goal – can only be realised by bringing together the totality of cross-cultural translations of the gospel and the totality of the experiences of different generations of Christians. Consequently, the necessity for African Christians to be both African and Christian without apology or feeling of inferiority wherever they find themselves is underscored by the supreme weightiness of missio Dei. Anything short of this withdraws from the beauty of the mosaic of God’s unique revelation in Christ to different groups of people in different places at different eras. Indeed, Christians who give up their cultural identity in exchange for that of another sell themselves short on partaking of the true flavours of the fruit of Christianity among them – and worse, those who make them do so are standing in the way of the Light of the World. May a fire of intentionality come upon the church in Africa and its diaspora and birth deliberateness in her efforts to acknowledge the great gifts God has given to her youth and see to it that these gifts be delivered to the world at large for the sake of God’s mission. Amen.

About the author

Joseph Ola holds master’s degrees in African Christianity and in Biblical and Pastoral Theology from Liverpool Hope University. He is a pastor in the Apostolic Church Liverpool, a youth mentor, and the founder of Alive Mentorship Group – an online mentoring platform for thousands of young adults across over 60 nations. An alumnus of London Pioneer School, Joseph is the author of over 10 books and a trustee of Missio Africanus. He is happily married to Anu, with whom he co-hosts Not Alone Today Podcast and Omolúàbí Podcast. They are blessed with two boys.

More from this issue

Notes

1 Scholars and historians like Andrew Walls and Thomas Oden have, in various works, chronicled the spread and impact of Christianity in Northern Africa in the first few centuries before the Islamic revolution. See Andrew F. Walls, “Africa in Christian History: Retrospect and Prospect,” Journal of African Christian Thought 1, no. 1 (1998): 2–15; Andrew F. Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2002); Andrew F. Walls, Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2006); Thomas C. Oden, How Africa Shaped the Christian Mind: Rediscovering the African Seedbed of Western Christianity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2007); Andrew F. Walls, Crossing Cultural Frontiers: Studies in the History of World Christianity, ed. Mark R. Gornik (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2017).

2 The official figure as of January 2021 is 684,931,000. See Gina A. Zurlo, Todd M. Johnson and Peter F. Crossing, “World Christianity and Mission 2021: Questions about the Future,” International Bulletin of Mission Research 45, no. 1 (2020): 23, doi.org/10.1177/2396939320966220.

3 See John S. Mbiti, “Main Features of Twenty-First Century Christianity in Africa,” Missio Africanus Journal of African Missiology 1, no. 2 (2016):72–88.

4 E. A. Ayandele, The Missionary Impact on Modern Nigeria 1842–1914: A Political and Social Analysis (London: Longmans, 1966); cited in Ogbu U. Kalu, “Introduction: The Shape and Flow of African Church Historiography,” in African Christianity: An African Story, ed. Ogbu U. Kalu (Pretoria, South Africa: Dept. of Church History, University of Pretoria, 2005), 3.

5 Adiele Eberechukwu Afigbo, Ropes of Sand: Studies in Igbo History and Culture (Ibadan: Oxford University Press, 1981), 384.

6 Hence Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator’s satirical subtitle to his book Religion and Faith in Africa: Confessions of an Animist (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2018).

7 For example, in the Nigerian context, see Luke Mbefo, “Theology and Inculturation: The Nigerian Experience,” CrossCurrents 37, no. 4 (1987): 395, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24459367.

8 Harvey Kwiyani, “Moya Chronicles and the Storying of African Christianity,” CMS Pioneer Mission, 10 May 2021, https://pioneer. churchmissionsociety.org/2021/05/moya-chronicles-and-the-storying-of-african-christianity/.

9 No identifying information was asked of participants who completed the survey online except for general demographic questions, neither were they given any incentives for their participation.

10 200 was chosen as the benchmark for the sample size in agreement with the research supervisor as a reasonable size for the current research. While power analysis had been proposed as the statistical means of determining an appropriate sample size for research, it is an unrealistic calculation for this current research especially because there is no previous similar research that can inform the statistical variables needed to calculate the sample size. See Kjell Erik Rudestam and Rae R. Newton, Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process, 4th ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2015), 119–20.

11 Diaspora respondents are from 14 countries: Canada, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Northern Cyprus, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Turkey, the UK, the USA and the UAE.

12 Yorubas, Igbos and Edos constitute the majority (90.4 per cent). Others include: Hausa, Efik, Ijaw, Utugwang, Gbari, Idoma, Urhobo, Andoni, Oworo, Tiv, Ebira, Eleme, Itsekiri and Igala ethnicities.

13 The question says, “Apart from the Bible, what book has influenced your Christian faith the most?”

14 Joseph Ola, “A Missiology for a Youthful Continent,” in Africa Bears Witness: Mission Theology and Praxis in the 21st Century, ed. Harvey Kwiyani (Nairobi, Kenya: African Theological Network Press, 2021).

15 Thom S. Rainer and Jess W. Rainer, The Millennials: Connecting to America’s Largest Generation (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group, 2011), 47.

16 Harvey C. Kwiyani, Our Children Need Roots and Wings: Equipping and Empowering Young Diaspora Africans for Life and Mission (Liverpool: Missio Africanus, 2019).

17 A term often used in reference to younger millennials or Gen Z kids because of their “affinity for electronic communication via computer, phone, television, etc. screens”. See Marie L. Radford and Lynn Silipigni Connaway, “‘Screenagers’ and Live Chat Reference: Living Up to the Promise,” Scan 26, no. 1 (2007): 31–39.

18 Thom and Jess Rainer found that “[m]ore than one-half (51 per cent) of the [American Millennial] generation says that their parents have a strongly positive influence on their lives.” See Rainer and Rainer, The Millennials.

19 Rainer and Rainer, The Millennials, 41.

20 Oasis International Limited, Africa Study Bible: New Living Translation, ed. Dr John Jusu (Tyndale House Publishers, 2016).

21 Africa Bible Commentary: A One-Volume Commentary Written by 70 African Scholars, ed. Tokunboh Adeyemo (Nairobi, Kenya: HippoBooks, 2010).

22 Rainer and Rainer, The Millennials.

23 Oyekan Owomoyela, Yoruba Proverbs (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 12.

24 Ubuntu is a philosophical concept of identity among the Ngunis of Southern Africa. It is often articulated through the dictum, “I am because we are, and since we are therefore I am” – highlighting interdependence as a common reality for all humans, such that one discovers the full import of one’s humanness through one’s interactions with others. See Barbara Nussbaum, “African Culture and Ubuntu: Reflections of a South African in America,” World Business Academy: Perspectives 17, no. 1 (2003): 2.

25 Ọmọlúàbí is to the Yorubas of West Africa what Ubuntu is to the Ngunis of Southern Africa – a conceptualisation of (noble) personhood and useful exemplification of African identity. See Olusola Victor Olanipekun, “Omoluabi: Re-thinking the Concept of Virtue in Yoruba Culture and Moral System,” Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies 10, no. 9 (2017): 219.

26 Joseph Ola and Anu Ola, “001 – Introduction to Ọmọlúàbí Podcast”, podcast audio, Omoluabi Podcast, 25 January 2021, https://www. josephkolawole.org/omoluabi.

27 See Africa Study Bible, “Why We Should Value our Youth,” TGC Africa, 13 March 2020, https://africa.thegospelcoalition.org/article/valueour- youth-africa-study-bible/; David E. Kiwuwa, “Africa is young. Why are its leaders so old?” CNN, 29 October 2015, https://edition.cnn.com/2015/10/15/africa/africas-old-mens-club-op-ed-david-e-kiwuwa/index.html.

28 Acts 2:17, NRSV.

29 Faith & Leadership, “Andrew Walls: An exciting period in Christian history,” Faith and Leadership, 11 June 2011, https://www.faithandleadership.com/andrew-walls-exciting-period-christian-history.

30 For example, Edinburgh 1910 conference was tagged “Advancing the Kingdom of Christ” while Edinburgh 2010 conference was tagged “Joining in with the Spirit”.

31 Kirsteen Kim, “Edinburgh 1910 to 2010: From Kingdom to Spirit,” Journal of the European Pentecostal Theological Association 30, no. 2 (2010): 16.

32 Fr Vineeth Koshy, Youth Envisioning Ecumenical Mission: Shifting Ecumenical Mission Paradigms for Witnessing Christ Today (Edinburgh, 2010): 1, http://www.wcc2006.info/fileadmin/files/edinburgh2010/files/conference_docs/Parallel1_Koshy_youth.pdf.

33 Paul Ayokunle, “African Christian Parents and the Task of Parenting in the West,” Moya Chronicles 2, no. 10 (2021): 2, https://missioafricanus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Moya-Chronicles-13_compressed.pdf.

34 Some Christian communities in East Africa are already doing this. For example, see Godfrey Katumba, Solemn Communion: A Critical Examination of the Current Practices Surrounding the Completion of Christian Initiation in Masaka Diocese (Uganda, East Africa), African Theological Studies 15 (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 2019).

35 Dr Gina A. Zurlo, “The World as 100 Christians,” Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary, 29 January 2020, https://www.gordonconwell.edu/blog/100christians/.

36 Jeff Desjardins, “Mapped: The Median Age of the Population on Every Continent,” Visual Capitalist, 15 February 2019, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-the-median-age-of-every-continent/.