Anvil journal of theology and mission

Anaditj: the way things are. Knowing of God in Australia

by Denise Champion

This article is extracted from the prologue and chapter 2 of Denise Champion’s book Anaditj.[1]

It was the United Aboriginal Mission that took care of the spiritual development of Adnyamathanha people [in South Australia]. Sadly, though, the missionaries said, “You can come into church, but you must leave your culture at the door.”[2]

I don’t sit easily with Western theology. It is only recent in Australia – 200 years old. In that 200 years, though, it has been a pressure cooker of teachings. The Western faith tradition of Christianity has been forced on us. It is so different to my Adnyamathanha understanding of Anaditj, the way things are.

2020’s NAIDOC week theme was “Always was, always will be”.[3] That’s true when I think about our spirituality: “always was, always will be.” We’ve always been a group of people with a strong belief from the beginning of who we were and our connection to creation. Our understanding has survived the test of time. Thousands and thousands of years it has survived, albeit we’ve got bits and pieces of it now. Mind you, the compilers of the Bible also only had bits and pieces. They put that together and retained knowledge of God, largely through stories. Stories have been keepers of knowledge. It is the same with us. Our stories have been keepers of knowledge. They have relevance for life today even.

Why is our understanding so important that I don’t let it go?

For me it makes sense of the world – of my world – to know that Adnyamathanha world view hasn’t ended. It still does continue and live on. And it’s okay. We don’t have to be ostracised and looked at as heretics, people who are bringing a new gospel or an “ism” or syncretism.

The wisdom of Dark Emu

Wadu matyidi Arrawatanha nguthangka kenjaranha tha Yarta nguthangula Yarta vadiangha vanhi ukiangka watga. Arrawatanha wangkanangka milyurangha awi mangungha, milyara wangkanangka. Arrawatanha ngawarla muyu wanganaka.

In the beginning when Arrawatanha created the sky and the land, there was no flat land even. Arrawatanha spoke on the face of the waters, the wind was talking. The breath of Arrawatanha was speaking.

Gen. 1:1–2

The way we’ve been brought up, very conservative Western evangelical thinking was about division between light and dark. There were huge stereotypes. Born-again Christians lived in the light. They were children of light. Anything associated with light was the accepted norm but anything you did in the dark was bad. Black people were not the accepted norm.

We have to get a really healthy understanding of light and of darkness. We need the darkness.

I’ve come to read the Scriptures in a new way. I had only ever read the Scriptures going immediately to “God said let there be light”. But the other is very important: “Darkness, formless and void.” There’s something in the notion of light and darkness being equal partners.

In Aboriginal spirituality we have Dark Emu. It’s about the constellations. Western scientists look at the stars and the brightness of the Milky Way, but Aboriginal people have stories that include the dark spaces between the stars. One of those is about Dark Emu. It’s very sacred. You need the stars to see the Emu, but you can only see the stars in the dark.[4]

It’s a great thing, eh? We see the other in the picture, the dark alongside the stars. It’s a deep theological concept that invites us all to see the whole that is both.

People conveniently forget. We have only the one narrative of Australia: the understanding of a new Australia in which Aboriginal Australians were not identified as human. There are people who are still out there who think Aboriginal people are descended from apes, the missing link, proving Darwinian evolution. It was convenient that people didn’t see us because then “the land didn’t belong to anyone”.

I find it really difficult to read the Bible. After the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, bringing a return of Greek and Roman thinking, things were split. The Western world has that dualistic thinking that can be seen in the New Testament. The Old Testament is easier for me to read in terms of world view but I’ve grown up accepting that it’s all about Abraham. You only ever hear the Abraham narrative. That’s all that matters. “Father Abraham had many sons.” He may have been the father of many nations, but you don’t hear the story of the nations that his story is in. What are their stories? A lot is hidden. The story of the people of Canaan, for example, the indigenous peoples, is always told from the perspective of the victor. They are bad; they have many gods.

Tongan biblical scholar Jione Havea once asked a group I was part of, “Was it right that God’s people – the children of Abraham – went in and were given the order to slay all the people in Canaan?” I remember feeling angry about that because I identify with the children of Canaan, the indigenous people. That was one of the first times I found myself questioning how I felt about this story.

We are actually presented the biblical story in such a way that somehow we’re supposed to, or we should, accept it without any question. And we do! It was the voices of power abuse and spiritual abuse that would continually raise their voices higher and above ours, saying that we weren’t allowed to change anything in Scripture. Nothing. They would quote Rev. 22:18–19 at us:

I warn everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this book: if anyone adds to them, God will add to him the plagues described in this book, and if anyone takes away from the words of the book… God will take away his share in the tree of life and in the holy city.

We certainly weren’t allowed to question the Bible. But Jione’s question was a good way for me to start thinking critically about Scripture. As soon as I started asking questions, I was able to form my own opinions. Up until then we always had to just accept the voice of the missionary.

Uncle Bill Hollingsworth, the first chair of the United Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress at the time when Congress and the Uniting Church in Australia entered into Covenant, would always talk about us as a royal priesthood, a holy nation after the order of Melchizedek. I never quite understood why. But that’s one story that is “other”. It’s the first reference to an indigenous person in the land of Canaan and he is the king who “was priest of God Most High” (Gen. 14:18). When Abraham comes into this land, he’s met by this mystery man from another culture who blesses him in the name of God. And this man Melchizedek is not only priest but king as well. He was king of Salem, the city of peace, so he was a righteous king.

There’s something important about why he has been included. He holds knowledge that is older than Abraham’s story.

And then I could never figure out why the story of Melchizedek figures in the Jesus story. You have to look all the way over in Hebrews for that: “Jesus… designated by God a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek” (Heb. 5:7, 10). Of course, it’s a much older order. It was not of the Levitical priesthood, the chosen priesthood of the children of Israel. I have a sense that it is the priesthood of all Creation.

Echoes of familiarity

In Eternity in their Hearts, Don Richardson tells of the way cultures from around the world had already been prepared to receive what we now know as the gospel.[5] Because they were prepared, they recognised it as good news. They made the connection themselves; they didn’t have to wait for missionaries to tell them. The indigenous people made the connection.

Vincent Donovan in his book Christianity Rediscovered tells the story of the Masai people.[6] There had been 100 years of missionary activity among them. Nothing. Suddenly, after 100 years of trying, Donovan builds a relationship and they make the connections. The Masai embraced Christianity, making it their own. They didn’t have to change anything; they heard the story and told it in their way.

It’s the same with the people up in the Top End in Western Australia – First Nations peoples. Because ceremony and dance is so much a part of their culture they will sing the gospel. Some of them do try to translate the Christian story into their culture, but there is also an old belief in the Wandjina, the Rain Maker – their most significant Creator spirit. Wandjina were spiritual beings that were superior. They are characters with funny shaped heads, and no recognisable facial features; the people are trying to visualise spirit. That was thousands and thousands of years before missionaries came. In Our Mob, God’s Story, it is noted that “when the missionaries came to the Kimberley to share the Bible with the people, the old people responded that they already knew these stories”.[7]

I speak about religion as being stories of Creator – and as I understand Creator – because I think that sums up very closely what indigenous wisdom is. Our Adnyamathanha word for it is Ngalakanha Muda – Big History of Deep Wisdom.

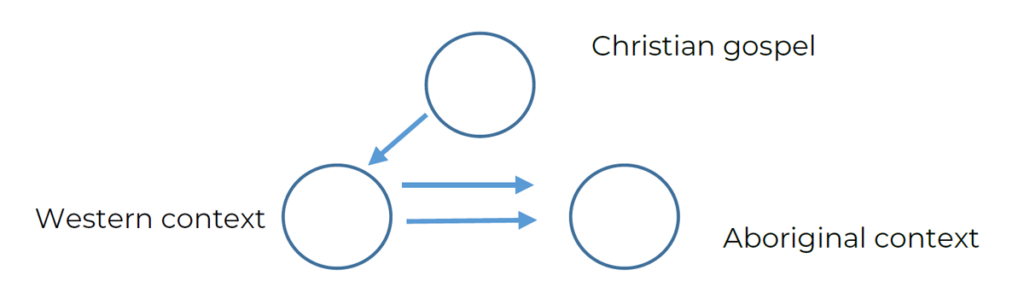

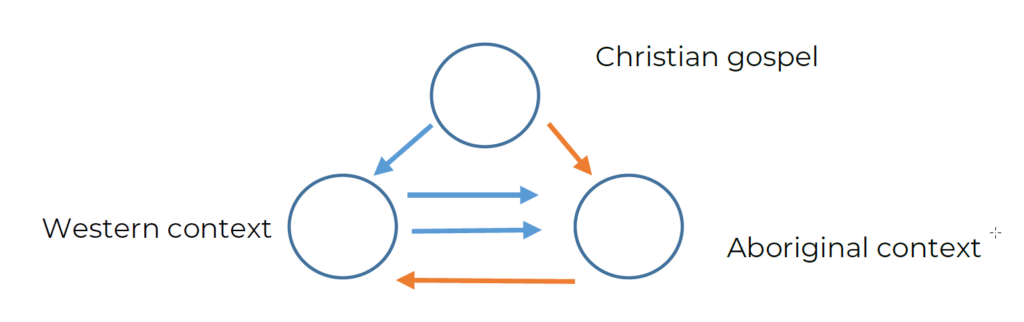

In the United Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress we had the following diagram:

Essentially the Christian gospel came via the Western context to the Aboriginal context. But our old people argued that there was always a connection between God and our Aboriginal context. God was always able to speak to us through our own culture.

I like the story of Paul in Athens (Acts 17:16–34). There he spoke in Mars Hill at the altar to the unknown god, but Paul didn’t follow the usual Greek practice in logic of starting at the beginning. He started the story of Jesus assuming that they’d heard the first part, so he doesn’t tell the story of Jesus’ earthly ministry but starts with the risen Christ. He told the story, and some asked him back again.

For Aboriginal people we’ve always known that there’s someone bigger who made the visible world around us. For a long while we weren’t able to tell of it, but God does speak to First Peoples in our context. It means we can go back a lot longer than 200 years ago, and even older than the invention of the printing press. Our oral knowledge and presentation of Creator in our stories enables us to go back before historical timelines.

There’s a much older story that has stood the test of time in this land. I recognise the story that’s told in the Bible because I’ve heard it somewhere before. It’s the echo of the much older story, of the universal Christ and the birth of the universal church.

The lesson of Big Boss Emu

If you don’t want to own your past history and there’s just a vacant vacuum there, it’s quite easy to start with a small reference and not bother looking beyond. The church is happy with one-liner explanations of the church and of God in Australia. What would be the point of looking at “pagan” peoples’ understanding?! It’s something the church would rather not have to do. Let’s keep our status quo. Let’s stay with the norm. But if I’m part of the other I want to explore what Christianity might look like from another perspective – from my perspective.

There is a Narangga story of how Spencer Gulf in South Australia was formed.[8] Port Augusta, where it is located, sits at the very tip of Spencer Gulf. We have lakes outside Port Augusta where the sea doesn’t quite come right up because they blocked it off down near the powerhouse. It belonged to every kind of bird and animal you can think of. They would drink at the water, which was fresh then. (Fresh water does come up from underground rivers here – only indigenous knowledge knows where these points are.) Every kind of animal and bird coexisted until one day the old Emu thought to himself, “I’m a bigger bird than everyone else. I can own this for myself.” So that’s what happened. He took the leg bone of a kangaroo and threw it and opened up the gulf. All the sea water came splashing in. It filled the fresh-water lakes and no one else could drink from the fresh water. Only the big boss Emu remained. This place that was a shared place became a place that no one else gets to own and share.

I love that little story because it talks about the way that people could live as one, live in community, but the actions of the Emu meant that nobody can drink from that beautiful water again. There’s no fresh water around here now.

Emu’s story makes me think of Rainbow Spirit Theology, where the elders spoke of a strangler fig seed dropped on a kauri branch by a bird and slowly over time reaching down fine hair-like roots that thicken and strangle the host.[9]

This is where I question, “What is the truth?” For generation after generation we had our stories told to us. That was then interrupted through colonisation. Then we were told that this other story – a completely different story – is truth. In the same breath we were told to cease telling our stories, to get rid of them. That was really hard to do, so we kept doing it in secret.

There has been talk over the years about finding an Australian spirituality but the spirituality we have is still not inclusive enough. Our ways are still regarded as “other”. In the parable of the Sower, the environment that seed is scattered over is really important. If you get the environment right, the seed will take root. From a Western point of view nothing else matters than the Western Christian gospel – the Western way has taken over everything – but the soil for an Australian spirituality lies in our stories, songs, customs and ceremonies and in our world view.

I really believe that the Western church needs to listen. They’re missing out.

The parable of the Lost Coin (Luke 15:8–10) is representative of all the things we have lost. We Aboriginal people have lost so much – land, language, children, self-worth and dignity. For us we thought we’d lost them forever. But now I’m finding that the Lost Coin is not only a story about the one lost coin but the story of the other nine. The community of faith cannot be complete until that one lost coin is restored. The church is never ever going to be what it was meant to be without indigenous knowledge. It’s so important to God who leaves the “household of faith” and goes out to look for the ones that are lost and to restore them. In the parable of the Lost Coin, however, I realise that God who has always been looking for us has diligently swept the house and the lost coin was always in the house. We were always in the house. “Oh, let’s send the missionaries out to save the lost out there.” But we and our knowing of God were already in the house!

As Aboriginal peoples we bring things to this community. We bring knowledge. We bring understanding. We bring wisdom. But the community is not complete until it is there. If the Western church thinks they can get along without us, they will never be complete.

The tricky thing is how do you tell this to a people who have been told and think they are lost?

And how do you tell this to a people who think they are found?

God in my language

Arrawatanha – Most High

The Bible begins, “In the beginning, God…” (Gen. 1:1). But what does that name mean? Why that name?!

Two words are the root of “God”: ǥuđan of Germanic origin and the Indo-European ǵhau(ə). They both mean “to call upon”.

I don’t like the word “God”. I don’t understand why the English translations use that word. When I speak a word in my language that is used to describe who God is, it usually is a doing word – God-in action. God didn’t just exist to be called upon; God was at work. That’s a different concept completely. Or why not the Hebrew word or another of the Old Testament words, all those other words that talked about God’s character and attributes? Like Elyōn, God Most High, a really precious insight. Originally it was a blessing from King Melchizedek, priest of God Most High, in his indigenous language, upon Abraham (Gen. 14:18–20).

In Adnyamathanha we have a name for Most High, and that is Arrawatanha. Arrawatanha is One who watches over everything and who creates, though the word we use is “make” – Nguthanha, Maker.

In the Genesis account of creation God spoke and things happened, things were made. It wasn’t just the speaking of them into being, it was the way they were made, which is where our stories come into play. It was the Red and Grey Kangaroo making the plains and the hills. It was the giant Serpents – Akarru – making the walls of Wilpena Pound, a synclinal basin in the Flinders Ranges. You see the rising up of land or the appearing or coming into being of land. It was always a rising up into existence. The very thought of it was the breath. God thought, spoke and it came into being.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the Flinders Ranges, there’s a depression in the land where in wintertime the adatamadapa (ice) falls and forms on the ground. Women let down their silver locks from the stars and the long threads of their hair formed the ice on the plain. This is our connection in our stories to the Ice Age. It figures in the Muda (deep wisdom) about Artunyi, the Seven Sisters (Pleiades). Artunyi began their journey at Top End and travelled through all Aboriginal groups. From up north they visited places. When they spoke, their words formed the wind and things came into being. In many stories the Seven Sisters created. They didn’t procreate; it was begetting – nguthangkadna (the action of making/doing).

For us as Adnyamathanha we say things like ngami na ngapula nguthangka – our mother made us. (Ngami is our word for mother.) We have many mothers in our matrilineal society. They are creating and acting in community, enabling us to know where we belong, where our safe space – our home – is so that if we ever get lost, we know where to go.

In many other stories there are different names for who did the making. They can be female and male. When it comes to spiritual things there’s no importance placed on gender. There’s male and female. You could be talking about God as mother or God as father. None is more important than the other, but each image has its own place. For Adnyamathanha our stories operate like that too. Some stories only the men tell, others only the women. But there are sacred sites where Creator was female.

The way we were taught Christianity, God was always male. Everything was from a male perspective because when the missionaries came their picture of God was male and the strong leader in the community was a white male minister. That became the norm and Adnyamathanha feminine understandings were silenced because Adnyamathanha culture was silenced.

In the Australian church today we should all have the freedom to name God in our own language and not feel a constraint of only using the English name for God otherwise it’s not Christianity. That’s why I deliberately use the name “Arrawatanha”. I feel affirmed in being made in the image of God. God has made me Adnyamathanha so why not speak in Adnyamathanha?

For our Adnyamathanha people this is very important. For Aboriginal groups around Australia and any indigenous peoples around the world, our cultural identity hasn’t been affirmed.

When I speak and use language I feel affirmed.

When my culture and language is affirmed that is Good News.

Ngalakanha Muda: The Word (John 1:1–14)

I have done a little bit of work on Christologies and wondering what does it have to do with my theology? The old missionaries would teach us about who this Jesus was. But if Jesus is over there in Israel what does Jesus have to do with us over here, in Australia?

If we listen to the opening of John’s Gospel (John 1), however, all that we have to recognise is that Christ is here and always was here.

- Wadu nguni wadu Ngalakanha Muda ikanga. Ngalakanha Muda ikangka Arrawatanhangha. Idina watya Ngalakanha Muda ikangka.

- Vanhi ukiangka watja Ngalakanha Muda ikangka Arrawatanhangha.

- Inhawatanha Ngalakanha Muda, Arrawatanha urru wirti nguthangka. Utanha wirti nguthangkulu Ngalakanha Muda vadiangka urrunha.

- Ngalakanha Muda ardla nungkangka urru ipi ikandyadna.

- In the beginning was the one who is called the Word. The Word was with God and was truly God.

- From the very beginning the Word was with God.

- And with this Word, God created all things. Nothing was made without the Word, everything that was created

- received its life from him and his light gave life to everyone.

In Adnyamathanha culture Ngalakanha Muda is a very big concept. It’s the most important framework and foundation and has always been there. It didn’t just begin 200 years ago.

In our stories, our Muda, we have these agents of creation helping to make things. Each Muda reveals Ngalakanha Muda, the big story of Creator being present. “In the beginning was the one who was called the Word” (John 1:1); Christ was Creator present in our stories – Ngalakanha Muda.

Our wise ones didn’t give away what they knew. They didn’t give out their knowledge freely. They would affirm things when they saw it and they understood it as special knowledge. They’d say, “That’s ngalakanha muda anadi” – that’s big wisdom that, big knowledge. As the Bible teaches, wisdom existed before anything else came into being (Prov. 8:22–31). That’s Ngalakanha Muda. If you begin with wisdom that becomes your compass. If you acknowledge that wisdom was there in the beginning it becomes guidance for your journey, and the eschaton – your end.

Undakarranha

Undakarranha is the one Adnyamathanha have recognised as the Christlike person. The one who has come back from the dead. He is a particular appearing.

Our understanding the resurrection is very important for bridging between Christ and Jesus.

I was trying to translate John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.”

“Have eternal life.” What does that mean? Eternal life? When is life not life? When it’s dead; Muyu vandendai – no breath. What would be the opposite – of having breath? Breath that lasts forever, that doesn’t die. Well, that’s got to do with spirit, so wangapi muyu – spirit breath. Christ enables us to live in the spirit because he is the one who has come back from the dead. That story is very important – someone who has come back from death and allows life to come back in a different form.

We have Muda, a story, that speaks to that. It’s about Aramburra, the trapdoor spider, and Artapudapuda, a grub. They have a conversation about what will happen when the body dies. Artapudapuda believed that once the body dies it returns to the ground where it came from and there it stays. Aramburra believed that once the body dies it returns to the ground but after three days the spirit would rise again. After many conversations they realised they needed to make a decision; they went with Artapudapuda’s version of the story. But as time went by, they began to miss their loved ones and regretted the decision they had made. To this day Aramburra can be seen but Artapudapuda cannot because he’s ashamed of the consequences of his version of the story.

In our language the word unda speaks of a deceased person. Undakarranha is our word for a person who comes back from the dead. So we held ancient knowledge of this idea. Undakarranha was a word that our elders identified Jesus as. They understood that he was the one that fitted that description so we as Adnyamathanha have embraced that.

Why did Jesus have to come back? So he could be universal.

Yet that night when Jesus rose from the dead the two who walked on the road didn’t recognise him. The ones at the tomb missed him. Jesus means “one who saves”. He was the one they were looking for but even when he came, they didn’t recognise him. They didn’t recognise Christ among them. They were still looking through their physical eyes, but Christ is not something you can see just through your physical eyes. Recognition requires spiritual sight also.

I heard an African proverb that talks of mothers using material to tie their babies on their backs. The proverb pointed to the fact that the gospel or Jesus or Christ has become like that picture because we have wrapped Christ up in so much wrapping that we can’t see him anymore. We need to unwrap – decolonise – to be able to see. It’s much easier for me to think of Christ as Ngalakanha Muda than to think of Jesus Christ. We’ve been taught you can’t have one without the other, and in a sense it’s true, but who is it true for? The challenging bit for us is being able to be brave enough to look at Scripture and read it through our own eyes.

It’s been very problematic for aboriginal peoples the world over when the missionaries have quoted that verse where Jesus talks about being made known, and he says, “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9). In Australia us Aboriginal people have been caught up in wanting to see Jesus. But of course, Jesus was that one-moment-in-time revelation of who God is in flesh. And that was to a very specific group of people. For us to try and copy that, we can’t. Because it only happened once.

So what does it mean to be a follower of Jesus here in Australia? You obviously can’t go around walking in his footsteps. That’s where the idea of the universal Christ is important – not just Jesus.

Jesus came to his own and asked the question, “Who do you say that I am?” And they had to answer that, just like we are having to answer that. Who do you say that I am? That question is not a trick question that someone has the actual answer to. It’s an invitation to enter into a journey to discover who Christ is.

Our response is, “Nina urtyu Ngalakanha Muda. You are the Christ. Anaditj. You are Big History.” The beauty of that is that Christ has always been here. He didn’t need to come and be introduced to us. Christ is everywhere and in everything and in our story and always has been and always will be!

That almost sounds like a creed that could be repeated.

What would we therefore call ourselves? Would we call ourselves Christian? I think we would call ourselves Arrawatanha yura urapaku or Undakarranha yura urapaku – followers of the Most High, followers of Christ.

Our stories, our lens

Light was created first and then the sun was created. What is light? It’s what helps us see. It helps things grow. It helps new things come into focus, into being. Light needs to be shining all the time. The sun can’t shine all the time; half of the world is in daylight and half in dark. It has its hours of the day when it shines. But light is something different. It’s shining continuously – maybe in a different time and space.[10]

For us, when the Word becomes flesh, out of darkness something becomes light. Our stories, sacred and thousands of years older than the biblical record, are our lens through which we can clearly see.

About the author

The Revd Dr Aunty Denise Champion is Theologian in Residence at the Uniting College for Leadership and Theology (UCLT), Adelaide, South Australia. She is an Adnyamathanha storyteller, and her people have lived in the Flinders Ranges for at least – according to archaeology – 48,000 years. Denise Champion’s book Anaditj can be obtained at https://www.mediacomeducation.org.au/shop/anaditj/

Dr Rosemary Dewerse, Academic Dean of UCLT, has been collaborating with Aunty Denise since 2012 to publish her perspective and wisdom.

More from this issue

Notes

[1] Denise Champion, Anaditji (Port Augusta: Denise Champion, 2021). The book can be obtained at https://www.mediacomeducation.org.au/ shop/anaditj/

[2] Denise Champion, Yarta Wandatha (Adelaide: Denise Champion, 2014), 17.

[3] NAIDOC is an annual celebration every July in Australia of the cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

[4] “Emus were creator spirits that used to fly and look over the land. To spot the emu, look south to the Southern Cross; the dark cloud between the stars is the head, while the neck, body and legs are formed from dust lanes stretching across the Milky Way.” ABC Radio Sydney, “Aboriginal astronomy the star of Dreamtime stories,” ABC News (5 April 2017), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-04-05/aboriginal-astronomy-basis-of-dreamtime-stories-stargazing/8413492.

[5] Don Richardson, Eternity in Their Hearts: Startling Evidence of Belief in the One True God in Hundreds of Cultures Throughout the World (Bloomington, MN: Bethany House Publishers, 1981).

[6] Vincent J. Donovan, Christianity Rediscovered (Chicago: Fides/Claretian Press, 1978).

[7] Kirsty Burgu, “3 Tribes, Wandjina,” in Our Mob: God’s Story: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Share Their Faith, eds. Louise Sherman and Christobel Mattingley (Sydney: Bible Society Australia, 2017), 208.

[8] The Narangga are Yorke Peninsula people (near Port Elliot) in South Australia.

[9] Rainbow Spirit Elders, Rainbow Spirit Theology: Towards an Australian Aboriginal Theology, 2nd ed. (Hindmarsh: ATF, 2007). First published 1997.

[10] “Light is not so much what you directly see as that by which you see everything else.” Richard Rohr, The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope for, and Believe (New York: Convergent Books, 2019).