Anvil journal of theology and mission

Business that sustains

by Rosie Hopley

In this article I am going to explore how people can thrive and be sustained in entrepreneurship.[1] I will reflect on whether it is possible to carry out sustainable entrepreneurship in the context of a “social business”, one which puts community outcomes above profit. Is this mission impossible or is there a way to thrive in faith, pioneering and in business?

Over the last decade, I have been interested in finding out how business and community endeavour can help people forge a pathway out of long-term unemployment and economic hardship. More recently, I have started to explore what it might mean to do business in such a way so that people can flourish through sustainable entrepreneurship. Building a thriving community is, I would argue, vital for successful entrepreneurship, and there are some tools and ways of thinking that might contribute to this. My focus in this article will be the member care model and ubuntu.

I was introduced to the member care model by Tearfund in 2015,[2] and I adapted it for a ministry, in Bristol, called Beloved, which provides practical, emotional and chaplaincy support to women working in any part of the indoor sex industry.[3] Having seen the success of this model for caring for outreach teams visiting women working in massage parlours in Bristol, in early 2022 I started to explore whether it might be adapted for LoveWell,[4] a small and growing social enterprise that produces beauty and skincare products.

Pioneering for social good

The Department for Business Innovation & Skills defines a social enterprise as “a business with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders and owners”.[5] This definition demonstrates some of the elements that need to be balanced in harmony in sustainable entrepreneurship – pioneering, growth, profitability. Without the profit, you won’t have enough money to reinvest and do good in the community or the business. Without growth, you will hamper the size and reach of your social business. For success, you need pioneers who are brave enough to forge a new way of doing their business that allows it to flourish. Perhaps this sounds idealistic – impossible, even? But I would argue it is entirely possible to aim for growth alongside support for beneficiaries/staff, as a major element of social business is that it works with people who have additional needs.[6] So, how do we integrate community into doing business, and in particular in a social business and enterprise? To explore this I turn to my own experience as a co-founder of LoveWell.

Finding community in a workplace setting

LoveWell was born out of a desire to offer an employment and training pathway for women who have experienced significant trauma through trafficking and exploitation – it was set up to see women thrive in a holistic workplace setting. I was a co-founder of the business with two other women. All of us had previous experience of setting up our own businesses.

LoveWell is a social enterprise that supports and trains women to build new skills through the manufacture of luxury natural skincare products. It currently has a team of five part-time staff and takes on six to eight trainees each year for a six-month training and development programme. The goal of this social enterprise is to expand to employ more women and to enable trainees to progress into long-term employment or to set up their own small businesses. To date, recruits have been employed and trained two days a week in the six-month programme, focusing on holistic training and production skills. Other skills in the development programme include maths and English, teamwork, home budgeting, CV-writing, job applications and production skills for handmade skincare products. Eighty per cent of graduates from LoveWell’s first Work Well programme made positive moves into further education, training, employment and employability support. In future, it will be exploring a one day a week model, in order to expand the offer to more women.

Contextualising the member care model

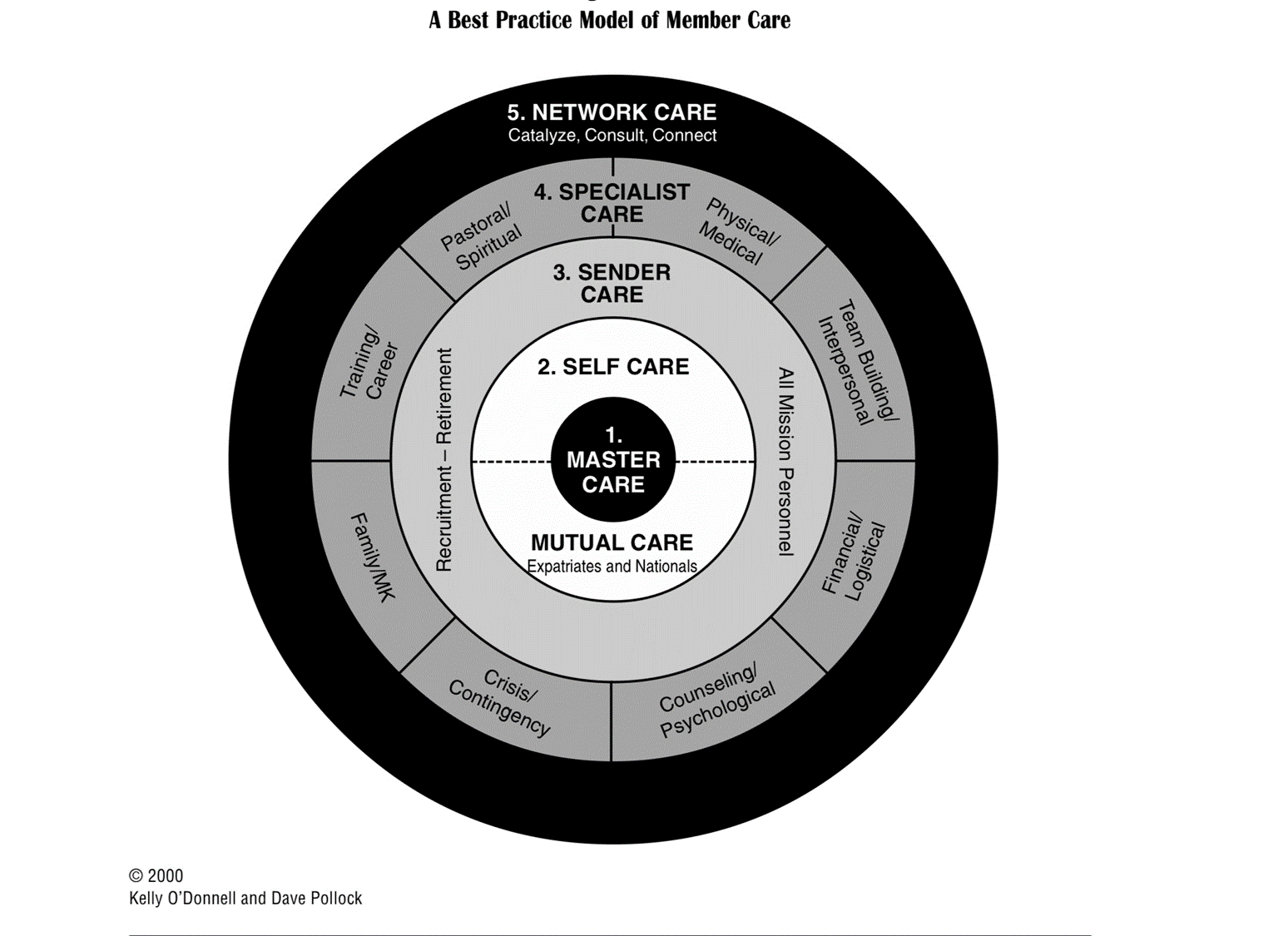

The member care model (shown in Figure 1), developed by Kelly O’Donnell and Dave Pollock for missionary care work, has been used in multiple contexts across the world. The model offers a framework for caring for Christian workers and volunteers. The model begins with an individual’s care, being cared for by their master, their maker. For example, we might understand this by asking a worker when they feel most nourished by God, or what helps to bring them into his presence. In growing concentric circles, we see other forms of care have their part to play, such as self-care (looking after yourself) and mutual care (looking after others in your team). In the model we can explore what being part of a church community looks like for the person, and how they are involving their community as part of being on mission. We think about and find different ways of care as it might be expressed in family, community and church contexts.

Specialist care is where we consider how the employer or sending organisation plays its part in taking responsibility for caring for its members. This might include team prayer, meals together, visits to teams (if overseas), group or one-to-one supervision, peer debrief, clinical debrief and people development. Finally, we come to the outermost circle of network care, which might include things such as connecting with national or international training bodies or connecting its wider networks for peer support.

I aim to see whether the member care model can be adapted for use with LoveWell, albeit in the context of a social enterprise. Working closely together with another LoveWell co-founder, Claire Dormand, and the LoveWell team, we are discovering how transferable aspects of member care are into an enterprise that has a focus on social good in the context of trainees’ experience of significant trauma through trafficking and exploitation. Aspects that will need some adjustment will focus on stages 1 to 5 of the model so that it is contextualised for LoveWell’s pioneering work.

It will be interesting to see how this adapted model evolves as the team grows, builds up its following among customers and retail outlets, and helps more women make the changes they want to see happen in their lives. How will sustainable entrepreneurship find its expression in ways that meet customer demand and the need to be profitable?

Community, communication and connecting

Community, communication and connecting via renewal spaces are all vital for enabling LoveWell to grow steadily, profitably and in a way that sees its team flourishing.

- Community means getting a good match between trainees, staff and volunteers so they are all committed to working together towards a singular vision. This is the ground bed necessary for helping trainees and the pioneering team to flourish as individuals and as a group.

- Communication is about helping trainees, staff and volunteers to communicate the vision and the larger story as LoveWell builds a gathering of customers into this community – in other words, gaining champions for the community who understand what makes these particular products stand out from the rest of the market. It’s a unique way of working together, to enable women to escape various forms of coercion and a powerful counter narrative for those who have previously lived with experience of exploitation.

- Connecting entails developing intentional spaces and understanding how such restorative spaces are inhabited by the LoveWell team, so they find rest, refreshment and meaning. These would include shared meals and hospitality, socials and reflection. In addition to spiritual and personal restorative spaces that might be in church or wider community, more conventional business practices such as supervision, training and people development also have a vital part to play. Being connected intentionally is a particularly important aspect of developing entrepreneurship that is sustainable.

In LoveWell, through these three Cs of community, communication and connection, women are finding a place of belonging, a place where they can learn to trust others and to take pride in their individuality and being part of a collective business effort. The member care model also enables the LoveWell community to embrace faith and belief, life and pioneering. As a learning organisation, LoveWell has positioned itself in the UK beauty industry by focusing on holistic wholeness, well-being and empowering women within its workforce. Everyone involved in LoveWell is committed to producing high-end products. For example, it develops a new product with each training cohort, with trainees taking responsibility for selecting scents, taking product images/photos and naming the final product.

There are limitations with regards to contextualising stages 1 to 3 of the member care model. As the organisation grows, it is likely there will be people with no faith or another faith who join the team. How therefore does LoveWell adapt this model for supporting entrepreneurs for the longevity of its work, in a context that might feature multiplicity of belief systems?

The team are grappling with these questions right now:

- How do we adapt this for people who wouldn’t have the view that they have been sent by others?

- How could we take a more spiritual view of this for those with other or no faith? Or for someone who doesn’t ascribe any spiritual aspect to life?

- How do we make this culturally relevant to women from other countries but also from other cultures – for example, not just middle class and Christian backgrounds?

It would appear that there might be limited scope for some aspects of the model to be adapted in light of these questions. An alternative framework that lends itself better to the flourishing of a diverse team is ubuntu.

Ubuntu as resistance

Ubuntu is a philosophy that is rooted in Africa. It is a community way of thinking summed up in the saying “I belong, therefore I am”. It can be understood as a means of resistance to hyper-consumption when built into business practices. After decades of global economic development, it is increasingly recognised that many parts of the world, much of it in the West, cannot keep producing and consuming at an accelerated rate. Such rapacious consumption with insufficient thought to sustainability and environmental impact is having a harmful impact on people, animals and the planet. Sustainable, just economies recognise there is a need to function in a different way if we – people, animals, planet – are to flourish and thrive.

This led me to think about how the principles of ubuntu might lend themselves well to a social business. The growth of social business is helping to usher in ways of resisting hyper-production and hyper-consumption business models, and pointing to a more humane, kinder, even humbler way of working. Is the West ready to embrace management and business lessons from Africa? For example, there are underappreciated principles held within ubuntu that we would do well to take heed of and replicate here in the West. These concepts point to the community and the individual, saying “I am, because we are”.

Bringing ubuntu into Bristol business

In her paper on postcolonial and anti-colonial reading of “African” leadership and management, Stella M. Nkomo explores how ubuntu speaks into community, caring, hospitality and more.[8] This resonates for social businesses that aim to do business in a different way from the traditional capitalist model. Mzami P. Mangaliso defined ubuntu as:

Humaneness – a pervasive spirit of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness – that individuals and groups display for one another. Ubuntu is the foundation for the basic values that manifest in the ways African people think and behave towards each other and everyone else they encounter.[9]

LoveWell has a very strong caring and community ethos, and although it is still a relatively new enterprise, it is showing some resonance with the concepts of caring and community, hospitality, respect and responsiveness.

Ubuntu theology in social business practice

Archbishop Desmond Tutu shared his view of how ubuntu enables all who live by its principles to take a more expansive approach to life in all its fullness:

A person with ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good; for he or she has a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole and is diminished when others are humiliated or diminished, when others are tortured or oppressed.[10]

There is an irresistible correlation here between Archbishop Tutu’s words and Jesus’ commands to “Love your neighbour as yourself”.[11]

Suppose we take a view that our colleagues, our customers, our suppliers are our neighbours, and that by doing business with one another following ubuntu practices, we can show that each person belongs to a greater whole? Surely, our way of working in such a way would lead us away from aggressive business and capitalist practices that grind others down to the lowest possible supply price, characterised by business boards and shareholders making ever bigger profits and dividends, larger salaries and normalising oppressive working practices. Following the Lord’s invitation and embracing ubuntu, we can find a different way: a way to do business so that we thrive, you thrive and together we take care of our planet. It encompasses a way of helping each other to flourish, as opposed to being diminished or oppressed. By slowing down, being intentional in our ways of being social, it is possible to take steps towards carrying out sustainable entrepreneurship. In answer to our first question, we do not have to face a mission that is impossible. In community, together we can find a way to thrive in faith, pioneering and business. It might look slower, more localised and be more embedded in the community. And I’m all for that – are you?

About the author

Rosie Hopley is founder and former CEO of the Christian charity Beloved and co-founder of social enterprise LoveWell. She enjoys learning about God’s reconciling love and writing. In 2021, she wrote the Reconciled Church Course.

More from this issue

Notes

[1] This piece is based on a seminar on sustainable entrepreneurship given at the Pioneer Mission Leadership Conversations day held by Church Mission Society and Northern Mission Centre in April 2022.

[2] Kelly O’Donnell, “Going Global: A Member Care Model for Best Practice,” in Kelly O’Donnell, ed., Doing Member Care Well: Perspectives and Practices from Around the World, (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2002), 16.

[3] Beloved provides practical, emotional and chaplaincy support to women working in any part of the indoor sex industry. For more information see https://beloved.org.uk.

[4] LoveWell is a social business in Bristol offering employment and support for women who have experienced significant trauma through trafficking and exploitation. See more about LoveWell here: https://lovewelluk.com/pages/our-mission

[5] “A Guide to Legal Forms for Social Enterprise,” Department for Business Innovation & Skills (November 2011), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31677/11-1400-guide-legal-forms-for-social-enterprise.pdf, 2.

[6] Thank you to Claire Dormand, co-founder of LoveWell, for providing additional thinking on this area.

[7] O’Donnell, “Going Global,” 16.

[8] Stella M. Nkomo, “A postcolonial and anti-colonial reading of ‘African’ leadership and management in organization studies: tensions, contradictions and possibilities,” Organization 18, no. 3 (2011), 365–86.

[9] For more of an exploration of these ideas, see Mzamo P. Mangaliso, “Building Competitive Advantage from ‘Ubuntu’: Management Lessons from South Africa,” Academy of Management Executive 15, no. 3 (2001), 23–33. See more here: Mzamo P. Mangaliso, Nomazengele A. Mangaliso, Bradford J. Knipes, Leah Z. B. Ndanga, and Howard Jean-Denisa, “Invoking Ubuntu Philosophy as a Source of Harmonious Organizational Management,” Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings 2018, no. 1, 15007, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagram-of-Ubuntu-Inspired-Change-Management_fig1_326277803.

[10] Archbishop Desmond Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness (London: Rider, 1999), 35.

[11] Matthew 22:39 (NIV).