Anvil journal of theology and mission

Colonialism, missions and the imagination: illustrations from Uganda

by Angus Crichton

I begin with a confession. I am a white British author writing about European colonialism and Christian mission in Africa within an Anvil issue devoted to racial justice. I can’t offer any special pleading in mitigation, so this is what I can offer you.

This article details how European missionaries and African Christians engaged with the onset of British colonialism in one African country.1 I will give concrete historical examples that bring pain and anger to black people and shame to white people like me. For these very reasons it is a story that still must be told and yet we can be reluctant to hear it. In part this article came to be written because a supporter wrote to Church Mission Society (CMS) with concerns about a Wikipedia page describing CMS missionaries as complicit in the British colonial takeover of Uganda.2 From what follows, you can judge if this concern is warranted. As with those we love in our families, Christian organisations also have their deficiencies as well as their glories. The church and the Kingdom of God are never one and the same: at its best the church points to Christ, at its worst it is a scandal before Christ. This is a story with much scandal, but also glimpses of the Kingdom.

European missionaries in an independent African kingdom

The missionaries of the Anglican Church Missionary Society and the Roman Catholic White Fathers arrived in the kingdom of Buganda in the 1870s (see Figure 1 for map), following a well-developed trading system between the capital and the coast of East Africa and Egypt that had been pioneered by Muslim traders since the 1840s. These Europeans came to an independent African kingdom, with its own sophisticated structures and which exerted considerable regional influence both north and south of Lake Victoria. Like other foreigners, they only resided at the capital with the express permission of the Ganda monarch, Mutesa I. CMS’s first resident missionary in Buganda, Charles Wilson (aged 26) spent his first six months in the capital without another European missionary. He and his team of coastal porters and craftsmen were completely dependent on the Ganda court for their accommodation and daily sustenance. To even communicate, including to preach, Wilson’s English was translated into first the regional trade language Kiswahili and then Luganda.

His position became more marginal when the Ganda chiefs arranged for his expulsion to a more remote residence from the palace. When he failed to comply with Mutesa’s requests for firearms, he and his party went without food for days at a time.

Wilson’s experience was to characterise European missionary experience in Buganda for more than a decade. Mutesa was past master at playing the emerging religious factions off against each other: Anglican, Catholic, Muslim, traditionalist. Missionaries who offended were barred from court, or worse banished to Lake Victoria’s southern shore. Ganda converts to all three external religions were killed on the monarch’s orders during the 1870s and 1880s. An incoming Anglican missionary bishop and his 50 African and Asian followers rode roughshod over court sensibilities as to who could enter the kingdom from where. It cost them their lives. As the religious identities of Ganda converts fused into political and military groupings, winners took the kingdom, losers were banished in multiple cycles of alliances, victories and defeats, with external European agents only playing a decisive role in the latter stages. European missionaries in Uganda entered initially as guests of and were dependent on the Ganda monarch at multiple levels, their presence only tolerated because of what the court wanted from them: guns (and other European trade goods) not the gospel, alliances with encroaching external powers for Buganda’s benefit and the wondrous tool of literacy.

European missionaries and the colonisation of an independent African kingdom

The missionaries’ dependent position altered in the 1890s as Belgian, British, Egyptian, French and German agents impinged on Buganda and her neighbours. CMS missionaries on the ground and administrators back in London were swift to lobby for the extension of British power into Buganda. In this they were continuing three decades of anti-slavery campaigning, missionary enthusiasm, private British commercial initiatives and British government policy in East Africa. It was the mercenaries of a British trading company with their maxim guns that intervened decisively on the side of the numerically inferior Anglican politico-religious party to catapult them to power. The resulting political settlement privileged Anglicans over and above the other politico-religious groups in terms of chiefly offices and therefore landholding. It is a settlement that has blighted Ugandan politics with instability and division ever since. CMS in London firstly advocated this trading company to remain in Buganda and raised £16,500 from the British public to enable this, and then actively lobbied the British government for Buganda to become a British protectorate.3 The White Fathers similarly were not slow to advocate for an alternative European power in the region deemed more supportive of Catholic Christianity, in this case Germany. CMS and White Fathers missionaries were actively involved in negotiations between Ganda chiefs and British officials in the signing of the agreement that placed Buganda under British “protection”.

This agreement transformed Buganda’s relationship with its neighbours. Buganda had overreached itself with commitments south of Lake Victoria and was facing eclipse, above all by neighbouring Bunyoro. Now, allied with superior British military firepower, it was time to settle old scores. For the British, a convenient way to prevent the Ganda religio-political groups from relapsing into infighting while at the same time acquiring military glory all around was to launch a combined conquest of neighbouring Bunyoro to the west of Buganda.4 Suppressing Nyoro slave trading provided the useful justification, fuelled by prior hostile reporting from Samuel and Florence Baker, a British adventurer husband-and-wife team from the 1870s. Meanwhile the Ganda chief Semei Kakungulu saw no need to wait for British military support. With little more than a vague nod from a departing British agent of the crown, he and 2,000 Ganda followers (half armed with guns) set off eastwards and carved out for themselves a kingdom against disparate peoples (armed with spears and shields), some of whom had defeated a Ganda army back in 1884.5 Christian agents, both European and Baganda, accompanied these advances west and east. One CMS missionary and a Ganda deacon went as chaplains to the Ganda army invading Bunyoro, while another missionary fell into the role of supply officer for families of Sudanese mercenaries working for the British. Another CMS missionary decided to go on a holiday eastwards with his wife and ended up establishing a mission station in the shadow of Kakungulu’s fort. His Catholic counterpart stumbled into a pitched battle between Kakungulu and one of the eastern groups, negotiated the surrender of the latter, entertained Kakungulu to tea and obtained from him permission to start a Catholic mission in the area. Kakungulu had already taken with him an Anglican Muganda deacon and several Baganda evangelists. Anglican and Catholic missionaries saw these projections of Anglo–Ganda military and political power as providential opportunities to introduce Christianity into areas coming into what became the Uganda Protectorate. Military forts and mission stations can literally be mapped together onto the same geographic location in these eastern and western advances. Buganda provided both political and ecclesiastical agents in both locations, with Luganda imposed as the language, riding roughshod over local structures, languages and cultures. It bred deep resentment which flowered into local liberative movements in subsequent decades, both in and beyond the church. Hitching our missionary chariots to politico-military horsepower is a human, not just a European tendency, as these Ganda examples illustrate.

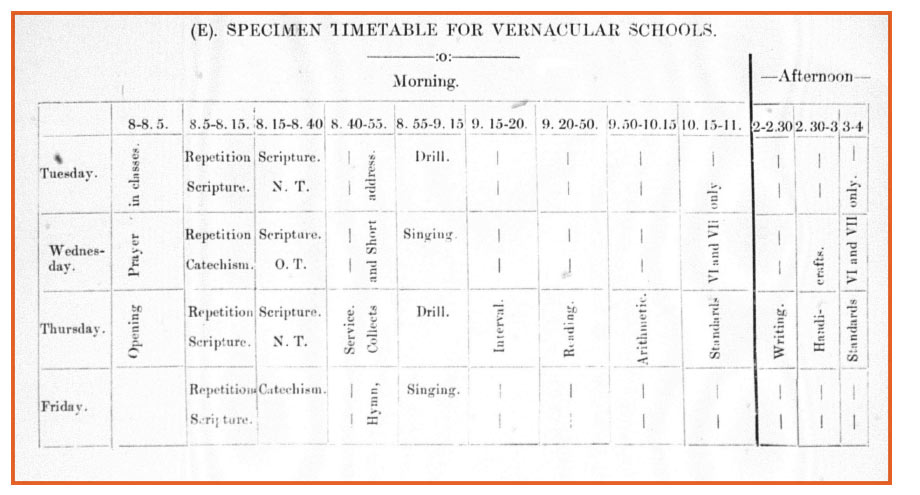

Always needing to run its empire on the cheap, the nascent colonial government devolved education, healthcare, the introduction of cash crops and novel industrial processes to the missions, making a series of grants in return. In all of these, the missions often proceeded as if there was little of value in pre-existing cultures of Uganda’s peoples. The syllabus taught in an Anglican village school was overwhelmingly European in orientation (Figure 2). CMS tended to sponsor Luganda publications that translated pre-existing titles by European authors rather than those by Ganda authors. Traditional therapeutic systems were labelled as both dangerous and sunk in witchcraft. Ganda family structures were swiftly labelled as incompatible with Christianity (as understood in Late-Victorian Britain). While CMS missionaries wrestled for decades with their response, most started with the assumption that “there is no true idea among the people generally of Christian family life.”6 Lambeth decreed in 1888 that the fruit of the vine must be used at the Lord’s table and over the next decade ruled out both the physical use of banana beer and its linguistic reference in the Luganda translation of the Prayer Book.7 Grape vines do not grow in tropical climates. This required wine to be shipped to the East African coast and carried a thousand miles inland on porters’ heads to Kampala and meant there was no obvious linguistic equivalent for use in the Luganda prayer book. When rendering into Luganda the demonic forces of the New Testament, the word for ancestors was chosen, the very people honoured by their communities for having lived exemplary lives and upon whom their wellbeing depended in succeeding generations. One CMS missionary applied Rudyard Kipling’s derogatory epithet to the peoples of northern Uganda, among whom he worked for over 30 years:

When, therefore, races are conscious of no power higher than the malignant capacity for mischief and the hardly invoked assistance in trouble which is all that they ascribe to their local demons, they are not likely to emerge from the slough of mingled savagery and folly which earns for them the description “Half devil and half child”.8

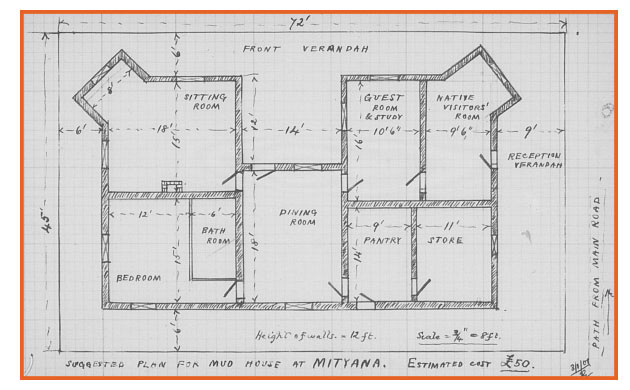

Such pejorative “Africans are…” sentiments were commonplace and therefore Africans required European tutelage to European Christian norms for decades to come. From the 1900s onwards, missionary housing was constructed with external verandas onto which a “native visitor’s room” opened (Figure 3), demarcating an external setting for European missionary/African interactions. The entanglements between Christian missions and colonialism were not only political, economic and military, they were also cultural and religious.

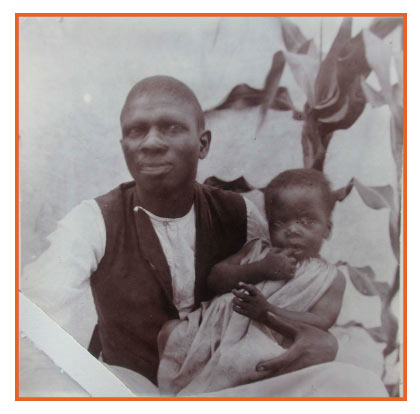

Yet this is not a monolithic story. The missions that welcomed European colonialism also questioned and even challenged it. In Uganda, the conflicting and contradictory nature of this relationship is well-illustrated in the person of Bishop Alfred Tucker, Uganda’s first Anglican bishop. On the one hand, it was Tucker who actively lobbied for Buganda to remain under British influence, was actively involved in negotiations between the Ganda chiefs and representatives of the British government and enthusiastically wrote back to CMS in London: “All has been divinely ordered, and already fruit is being borne. On April 1st the Union Jack was hosted at Kampala (the fort) and we all (missionaries) met together for special prayer and praise.”9 On the other hand Bishop Tucker also repeatedly protested to the colonial government in Uganda and in Britain about how oppressive their system of forced labour was to the African populations. He engaged in a 10-year battle with his fellow CMS missionaries to create a constitution for the Anglican Church that placed Europeans and Africans within a single structure. In doing so, the latter would have outvoted the former by virtue of sheer numbers (see Table 1 below) and so Europeans would have come under African control. The final result fudged the issue. The long-serving CMS missionary John Roscoe, in partnership with the Muganda prime minister Apolo Kaggwa, devoted many hours to researching Ganda customs, a sideline from his main church-based ministry. A fellow CMS missionary disparaged such pursuits as “hunt[ing] about in the dust bins and rubbish heaps of Uganda for the foolish and unclean customs of the people long thrown away.”10 Roscoe’s findings are of a similar quality to those of Kaggwa, standing the test of time. Yet his insights into Ganda marriage structures did not translate into his willingness to consider options beyond a rigid application of monogamy, even though the marriage practices of Old Testament patriarchs and monarchs, now rendered into Luganda, undermined this. In contrast, the African-led Anglican Church Council, constituted in 1893, took a more conciliatory approach to individual cases where four years of religio-political conflict had resulted in spouses being separated, killed and new partnerships formed. Occasionally one can see a CMS missionary collapse in their minds the cultural difference between a Muganda and a Briton. As the CMS missionary doctor Albert Cook reviews the objections to Christianity that Ganda villagers make to Ganda evangelists (rather than to a European missionary), he realises that he has heard similar reasoning back in Britain. Cook sees, while Tucker overlooks, Benjamani Nkalubo (Figure 4), who has remained in eastern Uganda, in the shadow of Kakungulu’s fort, while CMS missionaries have been invalided home. Nkalubo has lost first his son, then his wife, yet has persevered in his role as an evangelist: “Truly great things can be done with such teachers. Elijah’s mantle has not yet ceased falling.”11 These sentiments are rarer in comparison to those that disparage, demean or dismiss African sensibilities and abilities, yet they are there in the record alongside the latter.

| European missionaries | African clergy | African lay teachers | African Christians | Communi-cants | Scholars | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1887 | 3 | – | – | 300 | 50 | – |

| 1892 | 13 | – | 36 | 3,400 | 120 | 400 |

| 1897 | 43 | 10 | 521 | 14,457 | 3,343 | 742 |

| 1902 | 82 | 27 | 2,199 | 38,844 | 11,145 | 12,861 |

| 1907 | 104 | 30 | 2,036 | 65,433 | 18,078 | 32,393 |

(Statistics taken from statistical returns in CMS Annual Proceedings)

The relationship between Christian missions and the colonial government of Uganda took many twists and turns in the subsequent decades. It could be summarised as one of frustrated expectations on both sides. The missions hoped for preferential treatment for causes close to their heart, for example Christian marriage legislation and adequate resources to run their social service institutions. They were often disappointed by what they got in practice. Colonial governments hoped for uncritical support from missionaries with whom they shared a common national and religious identity, but were irritated by their partisanship and complaining. Ugandans frequently thought each supported the other. Colonial political control ended before missionary ecclesiastical control, with Bishop Kiwanuka’s Catholic diocese of Masaka to the west of Kampala being a notable exception, led by an all-African clergy by the end of the 1930s. A young CMS missionary, attending one of the first conferences on African history at Dar-es-Salaam in 1965, was gripped by the ferment surrounding missions and colonialism. Her searing honest reflections in her letter back to Britain received numbered annotations from a CMS administrator questioning or rejecting her insights.

African agency regardless of European colonial control

It would be possible to end such an analysis at this point. To do so would be a grave oversight, for it perpetuates the fallacy that European missionaries are the most significant agents in African Christianity. They never were. African Christianity is an African story: most Africans heard of Christ from other Africans. They appropriated the faith for their own reasons, sometimes bewildering European missionaries in the process. They forged theological insights, church practices and sociopolitical responses in the light of African realities. A few missionaries grasped this, increasingly from the 1960s; most expected their converts to resemble them. In Uganda, European political control lasted only two generations. There were those present when the British flag came down at independence in 1962 who remembered it going up in 1900. The Baganda Christian elite had their own very clear reasons why they wanted to sign a treaty with Britain in 1900. When a British imperial agent thought he could steamroll them into direct rule by British colonial officers, he received a rude awakening. The Baganda walked out of the negotiations with their kingship, chieftainships and council intact, landholding revolutionised and Buganda’s territory expanded beyond anything it had achieved in the last three centuries. Outworkings from this this treaty continue to haunt Uganda to this day, but one thing the Baganda elite were not is passive victims at the hands of British imperialism. Quite simply Europeans need to get over the sense of their own importance, both for good and for ill, in the African story.

Right from the outset of the Ugandan Christian story, Ugandan converts outstrip European missionaries (Table 1). The story is one of the leading examples, a result perhaps more of its chronicling than of its exceptionalism, of how African converts set the pace of the Christian advance, with European missionaries repeatedly playing catch-up. Rebecca Nkwebe Aliabatafudde first saw a European missionary when she went to seek baptism in 1886. Her entire instruction in literacy, in Christian faith and practice (including silent prayer), in the supply of precious Christian literature came from other Baganda Christians. Evangelists like Benjamani Nkalubo led this advance, initially from Buganda and then from other regions, utilising precolonial systems of exchange, as well of those opened up by colonialism, often traumatically so. It was they who first moved into a community, negotiated the right to remain with the local authority, gathered enquirers around them to learn to read and to pray. Some were severely persecuted for their efforts. Their salary was significantly less than those offered by the nascent colonial government, which needed western-educated Ugandans to interface between African subjects and European colonial administrators. Notable individuals such as Sira Dongo, Yohana Kitagana and Apolo Kivebulaya persevered for decades at their posts and are to whom entire Christian communities in northern and western Uganda and in eastern Congo look back to as their founders.

These early generations made the first moves away from a Europeanised understanding of the Christian faith. Apolo Kivebulaya instinctively demonstrated as well as proclaimed Christ’s power with healings in the manner of Elijah. The CMS missionary Robert Walker was bewildered by how Ganda converts could combine their newfound faith with heroic militarism. In contrast, for Apolo Kaggwa, prominent in battle on horseback, it was the failure of traditionalist bullets to find their mark that demonstrated divine favour for the Anglican cause in comparison to traditionalist folly. Most African religious systems have a strong thisworldly orientation, bringing blessing and warding off misfortune in this life with no compartmentalisation between the political and the sacred. Therefore within a Ganda religious framework, Kaggwa’s political theology is both intelligible and enduring while Walker’s is bizarre and has not stood the test of time for Ugandans. Where Christianity (and Islam) brought new information, it was the apocalyptic dimension that caught early converts’ imagination, producing anxiety about the overthrow of the existing world and subsequent judgement. The first generation of converts prized both acquiring and using literacy. If missionary-sponsored publishers privileged European authors, Baganda authors and entrepreneurs established their own publishing ventures, often short-lived, but from which a steady stream of Luganda publications emerged throughout the colonial period and beyond. A sole preoccupation with the catalogue of European-authored Luganda titles perpetuates a double injustice: not just the excluding of African voices, but the overlooking of African agency through alternative avenues. Ganda authors created their own structures to give voice to their own perspectives on life and faith without waiting for or needing European permission and assistance. Twenty years after the New Testament was published in Luganda, the Anglican synod decreed that the ancestors would no longer be equated with evil spirts and that a Greek loan word be used instead. While missionary-sponsored education dismissed and derided African cultures, it was that very same education that provided Ugandans with the tools and the pathway to challenge and overthrow colonial rule. While African-initiated Christian movements during the colonial period were rare in Uganda in comparison to neighbouring Kenya, Reuben Spartas broke away from Anglicanism to form an independent church “established for all right-thinking Africans, men who wish to be free in their own house, not always being thought of as boys.”12 When he finally settled on a home within the Greek Orthodox Church, he delighted in telling the CMS missionary bishop that he, Luther and other Reformation Protestants, not Spartas, were schismatics in the overall chronological sweep of church history. Africans were never just passive victims in the face of European political, cultural and ecclesiastical colonialism. Active resistance took many different forms as the Spirit of Christ inspired them to walk in the freedom and dignity that is theirs as image bearers of the divine and co-heirs with Christ.

The past in the present: apology, action and attitudes

As already indicated, I am hesitant to write on this subject. The above analysis is focused on one area and focuses in the main on the pre- and early-colonial periods. Certainly this case study cannot stand in for an entire continent or for other colonised continents. Interactions between diverse colonial regimes, missionary bodies, African churches and nationalist movements produced a wide range of responses to the issue under discussion. By focusing on a particular country, I wanted to avoid sweeping generalisation, instead attempting to reveal both the complexity of the relationship and its more disturbing aspects. The articles by Emmanuel Egbunu and Harvey Kwiyani in this edition of Anvil explore this relationship in Nigeria and Malawi, in the latter case expanding the focus beyond CMS to other missionary agents. Both also show how Africans struck out to create independent church structure beyond European control. The liberation theologians have taught us the first step is to identify and name the principalities and powers that reside within systems and structures. This is a small contribution to name these in one African country in one period. This naming must continue and to be voiced primarily by African scholars rather than individuals like me; the challenges facing the former I will comment on below.

Some may want to stop reading at this point. There is more than enough material here for you to formulate your own response to a path you have walked down countless times before in personal experience. You know what Ali Mazrui meant when he described the peoples of Africa as perhaps the most humiliated in history.13 Anything I write is second-hand and derivative, for you it is primary and personal. Harvey Kwiyani’s article is a strong example of the latter, going right to the very heart of Magomero, his home village in Malawi. However one of the many things I have learned from my African sisters and brothers such as Harvey over the last 20 years is that the issues here are in the present, not just the past. Indeed the present is shaped by the past, above all our imaginations. One of the most disturbing aspects of slavery, abolition and colonialism is images of African peoples that underlies all three, images based on woeful European ignorance. All presume that Africans are passive rather than active agents of their own destinies and therefore can be enslaved, liberated or ruled over by Europeans.14 Evidence abounds to the contrary; the above is but one collection of examples from a single location and period. Therefore a continued commitment to becoming less ignorant by learning from and with Africans is an appropriate European response to this toxic history. Those used to being “experts” need to realise they know nothing and listen. I am profoundly grateful for the African voices from books, through friendships, with students in the classroom and from the archive that have instructed this very white, ignorant Englishman (see further below). In that spirit, I am reluctant to say more, and yet what follows is a result of applying insights from the British parliamentarian Bell Ribeiro-Addy and the Indian parliamentarian Sharishi Tharoor as they reflected on Britain’s imperial legacy.15

Apology: Black people have been calling for decades for Europeans to issue an apology for the suffering and humiliation of African peoples through slavery and colonisation. In light of Black Lives Matter, some have heeded these calls, including the Church of England, underlining its 2006 apology.16 In June 2014 a service of thanksgiving and repentance on the 150th anniversary of Bishop Crowther’s consecration was held at Canterbury Cathedral. As I listened to the address by the then head of CMS, I could not hear the word “apology” or “sorry”. Emmanuel Egbunu at the end of his article comments on the Archbishop of Canterbury’s address at the same event, noting both his lauding of Crowther and his lamentation of European racism. The Archbishop’s apology comes in the opening paragraph of his sermon.17 While I have demonstrated this history defies a simplistic binary reading (black good, white bad), I have also shown that white CMS missionaries were actively involved in the political, economic, social, cultural and religious colonisation of black Ugandans. If we have “been on the wrong side of history not least when it comes to race” and want to “come afresh to the fountain of grace”,18 a clear, unequivocal apology is long overdue to our African brothers and sisters as well as to our Lord.

Action: Jesus warned us repeatedly that words without accompanying actions are meaningless. I have neither the wisdom nor the office to determine what this means for an organisation like Church Mission Society. However, I do know the posture required of us, as a CMS general secretary observed more than 20 years ago: “we must decrease that others may increase”.19 Phrases such as missio Dei trip easily off the tongue. Yet European decrease and African increase means reordering priorities, reimagining structures, declaring Ichabod to entire programmes, indeed organisations, based in Britain and working on the African continent. We prefer missio mei (the mission of me) in both its individual and institutional expressions, cutting covenants in our quest for security and significance. The fragile, pioneering movement of one generation consolidates into the self-perpetuating institution in another. The ongoing decline in British churchgoing computes across to the contraction of mission agencies. Endowments without donors severely curtails outreach. Therefore in practice British mission agencies have retracted missionary reach on other continents. They can no longer sustain their imagined leadership of the Christian faith in Africa. African churches in contrast have wisely chosen mass migration rather than the voluntary agency as their mission structure, moving in effect entire congregations to British shores, rather than isolated clusters of “professional” missionaries funded from Britain. The painful challenge for these African missionaries in Britain, just as for their British antecedents in Uganda, is to engage with a cultural and religious world so very alien to their own, compounded by that world’s often hostile attitude to black people.

This unwillingness to embrace African increase is all too apparent in the field I spend my days, that of researching and publishing African Christianity, where resources are still stubbornly concentrated in northern institutions. This is not an observation on crafting Christian thought globally, but specifically crafting Christian thought from and for Africa. Still the great library and archival collections are located in the north, opportunities for research grants and sabbaticals go to northern-based scholars, too much reflection on African Christianity is published in the north using structures that preclude return to the continent, not least the book’s price. Of course African scholars are not passively waiting for some northern-led solution to these issues, although these periodically still do fly and flounder. There are tremendous resources on the continent for the study of African Christianity, the greatest being living libraries of African Christians prophesying and praying, rejoicing and repenting, discerning and delivering, teaching and transforming. It is amazing not how little, but how much research and publishing is carried out by innovative African research and teaching institutions, all within a context and from a resource base that would stop comparable British organisations in their tracks. Yet this very group of scholars that need most access to some of the key primary sources, to interrogate and recast this toxic history, in practice have the most restricted access. Our readiness to embrace world Christianity, while functionally placing ourselves still at the centre, suggests our imaginations have yet to be liberated from colonial shackles.

Attitudes: My honest evaluation is that the demeaning images of African peoples logged in 19th century European hearts still reside within us all in the 21st. I make this statement on the basis of 30 years of experience in British churches and mission organisations with ministries in African countries. Rather than listing a catalogue of incidents, I will interrogate a single. I would describe such attitudes as reoccurring rather than occasional. The incident is the placement of my wife and me as CMS mission partners between 2005 and 2010 in Uganda, during which we encountered the following statements:

I expressed reservations to CMS staff in Britain about my being placed in a Ugandan theological institution because I had no experience of pastoral ministry in Uganda. I was informed that while the agency would not ‘send’ me to work in a British theological college, they would to one in Uganda.20

The Ugandan principal of this institution told me that a key benefit of having a British mission partner on staff was to keep the institution on the radar screen of Christian organisations and churches in Britain.

When my placement had the potential to move towards supporting Ugandan scholars to publish their research on Ugandan Christianity in Uganda, CMS staff in Britain observed that this would be harder for British sponsoring churches to connect with in comparison to my wife’s placement. Using her midwifery training, my wife supported teenage girls who had been driven from their homes because they had fallen pregnant outside of marriage.

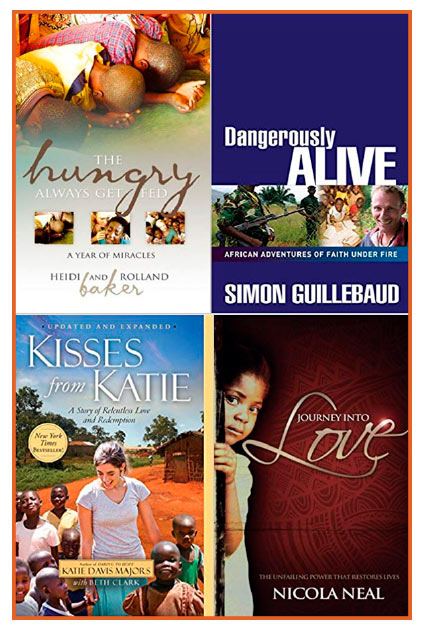

I list these statements not to question their pragmatic veracity nor to cast aspersions on the individuals concerned, all of whom have deliberately not been named. With no training in or experience of theological education, I indeed would not have been employed by a British college. My unease is with the underlying attitudes that are shared by all players, African and European, myself included. The great Ghanaian educator James Kwegyir Aggrey insisted that “nothing but the best is good enough for Africa.”21 Therefore why do British churches, a mission agency, a mission partner and a Ugandan theological institution think that a no-experience lecturer is good enough for Africa, but not for Britain? Why is a placement to facilitate the return to Uganda the fruits of Ugandan Christian scholars deemed more difficult for British churches to engage with than one supporting vulnerable, young Ugandan women? I suggest this is because a series of historic and damaging couplings: Africans are coupled with lack (of theological knowledge and the resources to address this) and helplessness (preyed upon young women rendered homeless); Europeans coupled with abundance (of theological knowledge, of finances, of skills) with which to elevate Africans. One only has to look at the bookstall of a major British Christian festival to see this attitude replicated on book covers: white people featured ‘saving’ black people (see Figure 5). Zac Niringiye laments how this has infected African imaginations as well:

Africa’s crisis is not poverty; it is not AIDS. Africa’s crisis is confidence. What decades of colonialism and missionary enterprise eroded among us is confidence. So a “national leader” from the United States comes—he may have a good-sized congregation, but he knows nothing about Africa! — and we defer to him. We don’t even tell him everything we are thinking, out of respect. We Africans must constantly repent of that sense of inferiority.22

So the principal made annual pilgrimages to the source of the radar signals to seek “support” for the theological college.23 Yet he found these signals both diminished and distorted: diminished by the gradual, relentless decline of British churchgoing; distorted because “support” is often (but not exclusively) attached to British mission partners.

While European political colonisation of African countries has now ended, its legacy lives on in our imaginations on both sides of the Mediterranean. We are deluding ourselves if we think any of us, European or African, are not infected today by four centuries of European humiliation of Africa and her peoples, notwithstanding four centuries of African resistance. European repentance must include not only apologies and actions, but repeated, ongoing cleansings of our imaginations. Otherwise history will continue to repeat itself. May the Lord have mercy on us all.

Testimonial postscript

It was above all through my placement with CMS in Uganda that this white, ignorant Englishman became more educated in the wonders of God on the great continent of Africa. As we sat in the congregation of the Anglican All Saints Cathedral in Kampala I witnessed with my eyes what I read about in books: a sermon on the political theology of the hills of Kampala; the power of the provost’s prayers over all others in the face of family calamity; echoing amens from the congregation to intercessions that renounced corporate sin to ward off Ebola — I could have been with Moses on Mount Ebal. My classes in the theological college were small and the dean never checked what I taught, so the inherited western theological syllabus went out the window. Instead my students and I embarked on experimental learning together. We visited the fourth Anglican cathedral built on Namirembe hill to critique its imported European architecture in comparison to the Ganda aesthetics of its three forerunners. We attended a day-long service at Samuel Kakande’s Synagogue of All Nations Church to explore approaches to healing and puzzled together on case studies which they brought on the same topic: was it prayers via the ancestors or via Jesus to the Creator God that brought the much desired baby? Some of the historical examples above have literally been pulled off lecture handouts from 13 years ago. To Martin Kabanda, Loyce Kembabazi (now late), Fred Kiwu, Shadrack Lukwago, Barbara Majoli (née Tumwine) and others, I owe more than I ever gave them, alongside inspirational mentors Paddy Musana, Zac Niringiye and Alfred Olwa. Our paths with Christ as he graciously invites us into his mission are more twisting than straight, exhibiting our and others’ grime as well as glory. And yet on these paths, the living God reveals to us glimpses of his kingdom. This white Englishman now inhabits a hugely expanded universe because he has witnessed the treasures of the peoples of Uganda turned to Christ in worship and service.

Bibliographic note

My understanding of the article’s subject matter is the result of 15 years’ learning about Ugandan Christianity. A key experience in this regard was my involvement in creating and publishing of the following book: Paddy Musana, Angus Crichton and Caroline Howell (eds.), The Ugandan Churches and the Political Centre: Cooperation, Co-option and Confrontation (Cambridge: Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide, 2017). On this title’s theme, my most significant tutors have been Zac Niringiye (for example see his chapters in Musana et al., The Ugandan Churches, 119–138, 239–260) and John Mary Waliggo (see “The Role of the Churches in the Democratisation Process in Uganda 1980–1993,” in The Christian Churches and the Democratisation of Africa, ed. Paul Gifford, (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 205–224). A bibliography of over 200 published and unpublished items on the Ugandan Churches and Politics is in “Appendix 2: Bibliography of the Ugandan Churches and the Political Centre,” in The Ugandan Churches, ed. Musana et al., 291–308. Sources I utilised are listed below, following the order of my article.

D.A. Low’s The Fabrication of Empire: The British and the Uganda Kingdoms, 1890–1902 (Cambridge: CUP, 2009) is a comprehensive overview of the British colonisation of Uganda making full use of both African and European sources. John V. Taylor’s The Growth of the Church in Buganda: an Attempt at Understanding (London: SCM Press, 1958) contains astute insights. Charles Wilson’s experiences are based on reading his correspondence to CMS for 1877 in CMSA (C A 6 O 25 Wilson).

For CMS actively campaigning and fundraising for the British Imperial East Africa Company to remain in Uganda, followed by it becoming a British protectorate, see D.A. Low, “British Public Opinion and ‘The Uganda Question’: October-December 1892,” in his Buganda in Modern History (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1971) 55–83.

Christianity’s advance into Bunyoro and eastern Uganda coupled with Anglo-Ganda political and military power summarises my own research published in “‘You will just remain pagans, and we will come and devour you’: Christian Expansion and Anglo-Ganda Power in Bunyoro and Bukedi,” in The Ugandan Churches, ed. Paddy Musana et al., 23–56.

My comments on Luganda Christian publications and translation issues are based on:

- my unpublished research in the archives of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledges and the British and Foreign Bible Society in the University Library Cambridge and the library of the International Committee of Christian Literature for Africa, transferred to the library of the School of Oriental and African Studies and listed in Michael Mann and Valerie Sanders, A Bibliography of African Language Texts in the Collection of the School of Oriental and African Studies University of London, to 1963 (London: Hans Zell, 1994), 56–68.

- Tim Manarin’s excellent unpublished PhD thesis “And the Word Became Kigambo: Language, Literacy and The Bible In Buganda” (PhD Thesis, Indiana University, 2008).

- John Rowe’s bibliography of published and unpublished Luganda titles “Myth, Memoir and Historical Admonition,” Uganda Journal 33.1 (1969): 17–40; 33:2 (1969): 217–19.

For an early example of negative attitudes to indigenous healing systems, see the CMS missionary Alexander Mackay’s comments of the Ganda deity Mukasa, whose priest was brought to court to heal Mutesa of a prolonged illness, probably gonorrhoea: [Mackay’s Sister], A.M. Mackay: Pioneer Missionary of the Church Missionary Society to Uganda (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1890), 145–77. Mackay’s confrontation with the traditional party at court, above all the queen mother Abakyala Muganzirwazzaza, proved disastrous and his influence declined markedly after that.

On missionary attitudes to Ganda marriage see Nakanyike Beatrice Musisi, “Transformations of Baganda Women: From the Earliest Times to the Demise of the Kingdom in 1966” (PhD Thesis: University of Toronto, 1991), 171–200.

I owe the architecture of CMS missionary houses in Uganda to Louise Pirouet, “Women Missionaries of the Church Missionary Society in Uganda 1896–1920,” in Missionary Ideologies in the Imperialist Era: 1880–1920, ed. Torben Christensen and William R. Hutchinson, (Aros: Aarhus, 1982), 236.

I owe the tension within Alfred Tucker to Christopher Byaruhanga, see “Bishop Alfred Robert Tucker of Uganda: a defender of colonialism or democracy?,” Uganda Journal 49 (2003): 1–7 and Bishop Alfred Robert Tucker and the Establishment of the African Anglican Church (Nairobi: WordAlive Publishers, 2008). See also Tudor Griffiths, “Bishop Alfred Tucker and the Establishment of a British Protectorate in Uganda 1890–94,” Journal of Religion in Africa 31:1 (2001): 92–114 and Joan Plubell Mattia, Walking the Rift: Idealism and Imperialism in East Africa, Alfred Robert Tucker (1890–1911) (Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2017). On Tucker and forced labour see Holger Bernt Hansen, “Forced Labour in a Missionary Context: A Study of Kasanvu in Early Twentieth-century Uganda,” Slavery and Abolition 14:1 (1993): 186–206. On the church constitution, see Holger Bernt Hansen, “European Ideas, Colonial Attitudes and African Realities: The Introduction of a Church Constitution in Uganda 1898–1909,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 13:2 (1980): 240–80.

On John Roscoe, see John Rowe’s review of Roscoe’s The Baganda (London: Macmillan, 1911), “Roscoe’s and Kagwa’s Baganda,”, The Journal of African History 8.1 (1967): 165–166 and Maud Michaud, “The Missionary and the Anthropologist: The Intellectual Friendship and Scientific Collaboration of the Reverend John Roscoe (CMS) and James G. Frazer, 1896–1932,” Studies in World Christianity 22:1 (2016): 57–74. Roscoe’s observations on polygamy is at CMSA G3 A7 O 1907/103 and The Baganda, 82–97. The different approach taken by the church council are based on reading the Minutes of the Mengo Church Council (Makerere University Library, Africana Section, AR/ CMS/123/1).

Albert Cook’s observations are in a letter to his mother 23 Nov 1903 (Wellcome Library London, Albert and Katherine Cook Archive, PP/COO/A163).

Benjamani Nkalubo’s letters are at Crabtree Papers (CMSA ACC27 F1/3).

On the Anglican church under British colonial rule, Holger Bernt Hansen’s Mission, Church and State in a Colonial Setting: Uganda 1890–1925 (London: Heinemann, 1984) is exhaustive for the early colonial period. Caroline Howell’s “‘In this time of ferment what is the function of the church?’: The Anglican and National Politics in Late Colonial Uganda” in The Ugandan Churches, ed. Musana et al., 57–76 is insightful for the late colonial period. The searingly honest reflections are those of Louise Pirouet in her annual letter to CMS for 1965 (CMSA, Pirouet, AF, AL 1965).

On the Uganda Agreement of 1900, the classic study is D. A. Low, “The Making and Implementation of the Uganda Agreement of 1900,” in D.A. Low and R Crawford Pratt, Buganda and British Overrule (Oxford: OUP, 1960) 3–159.

On African agency in the growth of Christianity in Uganda we are well served by Louise Pirouet, Black Evangelists: The Spread of Christianity in Uganda 1891–1914 (London: Rex Collins, 1978).

On Rebecca Nkwebe Alibatafudde, see “Rebecca Nkwebe Alibatafudde’s Story,” Dini Na Mila 2.2–3 (Dec 1968): 5–11. On Apolo Kivebulaya, see Anne Luck, African Saint: the Story of Apolo Kivebulaya (London: SCM Press, 1963) and now Emma Wild- Wood, The Mission of Apolo Kivebulaya: Religious Encounter and Social Change in the Great Lakes c. 1865–1935 (Oxford: James Currey, 2020). On Yohana Kitagana, see J. Nicolet, “An Apostle to the Rwenzori: Yohana Kitagana,” Occasional Research Papers 9, no 85 (Jan 1973). This is a translation from the booklet written originally in French and Runyankole by Father Nicolet, Un Apôtre du Rwenzori: Yohana Kitagana (Namur: Editions Grands Lacs, 1947). On Sira Dongo, see T. L. Lawrence, “Kwo Pa Ladit Canon Sira Dongo/The Life of Rev Canon Sira Dongo, The Apostle of the Lango and the Acholi, from a Slave to a Canon”. Acholi original and English Translation. English translation published in Source Material in Uganda History, Vol 4, (Dept. of History, Makerere: Kampala, 1971).

On Walker and Kaggwa’s political theology, see my article “You will remain pagans”, 45–47.

On Spartas, see F.W. Welbourn, East African Rebels (London: SCM Press, 1961), 77–110.

On Europe’s lamentable knowledge of Africa in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (when CMS was founded), see Philip D. Curtin, The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action 1780–1850 Vol 1 (Madison, University of Wisconsin: 1964), 3–57 and on the connections between abolition and empire, see Richard Huzzey, Freedom Burning: Anti-Slavery and Empire in Victorian Britain (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012).

Black-British writers insist that the past is in the present, for example Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I am No Longer Talking to White People about Race (London: Bloomsbury, 2017) 1–56 and Ben Lindsay, We Need to Talk about Race: Understanding the Black Experience in White Majority Churches (London: SPCK, 2019) 37–50. The latter reports Duke Kwon taking a similar approach to the two Parliamentarians I have followed here, see 46ff.

For a comprehensive and nuanced overview of the decline of religion in Britain, see Grace Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2015) and for its impact on Christian voluntary agencies, see Peter Brierley, The Tide is Running Out: What the English Church Attendance Survey Reveals (Eltham: Christian Research, 2000), 99.

On publishing African Christian thought, see Jesse N. K. Mugambi, “Ecumenical Contextual Theological Reflection in Eastern Africa 1989–1999,” in Challenges and Prospects of the Church in Africa: Theological Reflections of the 21st Century, eds. Nahashon W. Ndung’u and Philomena N. Mwaura, (Nairobi: Paulines, 2005), 17–29; Kyama Mugambi, “Publishing as a Frontier in the Development of Theological Discourse in Africa,” Hekima Review (forthcoming) and my own unpublished report to Ugandan theological institutions “A Survey of Postgraduate Research on Ugandan Christianity and its Dissemination” (Feb 2010).

About the author

Angus Crichton is a research associate of the Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide. He has supported Ugandan scholars to publish their research on Ugandan Christianity, both in Uganda and the global north. He conducts research on early Ugandan Christianity using archives in Europe and Uganda. He also works for SPCK supporting theological publishing from the global south for the global south.

More from this issue

Notes

1 Rather than clogging the text with endnotes, I have provided a bibliographic note at the end of this article listing the archives and publications on Ugandan history upon which I have based what follows should readers want to check my sources of information. I have also avoided indigenous terms often used in academic publications on Uganda. The article focuses in the main on Buganda, one of the precolonial kingdoms that was incorporated into the colonial creation Uganda (marked “Uganda” on the map in Fig. 1). The people of Buganda are the Baganda (single Muganda), their language Luganda, and I have used the Ganda as an adjective to apply to all things relating to the Baganda.

2 The problematic sentence was deemed to be: “A few years after, the English Church Missionary Society used the deaths [of the Uganda Martyrs] to enlist wider public support for the British acquisition of Uganda for the Empire” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uganda_ Martyrs).

3 This is around £1.4 million in today’s money, which would have been around 16 per cent of CMS’s income in 2019. In 1891–2, CMS’s income was £269,377, so the sum raised represented but 6 per cent of CMS’s income. The relative difference demonstrates the financial reach of CMS at the end of the nineteenth century in comparison to the twenty-first century.

4 Again Bunyoro is the name of the kingdom, Banyoro the people, Nyoro the adjective. On Fig. 1 Bunyoro is marked “Unyoro”.

5 Kakungulu’s advance stretched from Lake Kioga to Mount Elgon (see Fig. 1).

6 Martin Hall in The CMS Annual Proceedings 98 (1896–7), 120.

7 Further research is still needed on this topic. Frustratingly brief minute notes in the SPCK archive indicate that CMS translator George Pilkington’s suggestion of Luganda equivalents for bread and wine were referred to and rejected by Lambeth. However I have yet to confirm this by researching the Lambeth Palace archives. Bishop Tucker unsuccessfully lobbied Lambeth for banana wine to be used in communion in 1897.

8 A. L. Kitching, On the Backwaters of the Nile: Studies of Some Child Races of Central Africa (London and Leipzig: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912), 270.

9 Tucker to Stock, 16 April 1893, Church Missionary Society Archives (CMSA) G3 A5 O 1893/232.

10 Walker to Baylis, 13 March 1907, CMSA G3 A7 O 1907/98.

11 Albert R. Cook, Uganda Memories (Kampala: Uganda Society, 1945), 174.

12 Quoted in F. W. Welbourn, East African Rebels (London: SCM Press, 1961), 81.

13 Ali A. Mazrui, The African Condition: A Political Diagnosis. The Reith Lectures (London: Heinemann, 1980), 26.

14 Both British pro- and anti-slavery campaigns were united in their shared ignorance of Africa, the former marginally less so with some knowledge of the coast. For both, African societies were characterised, either by nature or through external European stimulation, as slaving societies, with attendant images of violence, depravity and heathenism. As anti-slavery arguments grew in acceptance, this generated pressure for the British government to become more involved in African countries to civilise, Christianise and provide alternative legitimate commerce. The terminus of this policy was British colonisation to eradicate slave trading. CMS’s advocacy for Britain taking control of Buganda is an example of this policy.

15 Bell Ribeiro-Addy made her comments during her maiden speech on 13 March 2020 and the relevant section can be watched at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gH9cVOwnUmo. Sharishi Tharoor’s eight minute articulate and impassioned contribution to the Oxford Union debate “This house believes that Britain owes reparations to her former colonies” on 28 May 2015 went viral and can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f7CW7S0zxv4. I was sent this material by my friend and colleague Dr Paddy Musana, as he observed Black Lives Matter from Uganda.

16 For details see the following statement on the Church of England’s website: https://www.churchofengland.org/more/media-centre/news/church-and-legacy-slavery

17 The Archbishop of Canterbury’s sermon is available at https://www.anglicannews.org/news/2014/06/archbishop-welby-on-the-first-black-anglican-bishop.aspx.

18 Quotations are from the executive leader’s address at the Crowther consecration anniversary, found at https://churchmissionsociety.org/our-stories/crowther-talk-canterbury-cathedral

19 Simon Barrington-Ward, “My Pilgrimage in Mission,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 23, no. 2 (April 1999): 64.

20 The language used in in the placement of mission partners is ambiguous. The idea of being sent is rooted in the idea of being called beyond ones immediate geographic and cultural context to minister in another and reflects the movement of missionaries from “the Christian west” to “the rest”. At a functional level I was employed by the Ugandan theological institution, but funded by British churches and individuals through CMS, an employment arrangement which would be decidedly irregular at a British theological college. However, my reservations were not about funding structures but about my appointment with no experience of either theological education or Ugandan pastoral life. Similar ambiguities surround the term “support”, see below.

21 Nnamdi Azikiwe, My Odyssey: an Autobiography (New York: Praeger, 1970), 37, 38.

22 Bishop Zac Niringiye interviewed by Andy Crouch, New Vision, 29 July 2006.

23 “Support” is a term often used by mission agencies to describe how individuals and churches join in partnership with an agency to send a a mission partner to minister in a particular setting, often beyond Britain. Such “support” consists of prayerful interest and regular financial giving towards the individual’s living and ministry costs and a contribution to the agency’s overheads.