Anvil journal of theology and mission

Contextual inhabitation: exploring the “where” of the pioneer charism

by Ed Olsworth-Peter

Introduction

Inhabiting the missional context is an important journey for all pioneers. In doing so they are able to form deep relationships beyond the walls of the existing church and to grow new Christian communities with those around them. This takes time and will be different depending on how embedded pioneers are within their context. Those engaged in a contextual approach vary in who they are, what they are growing, how they are growing it and where they are doing this. A one-size-fits-all approach may limit what can be achieved.

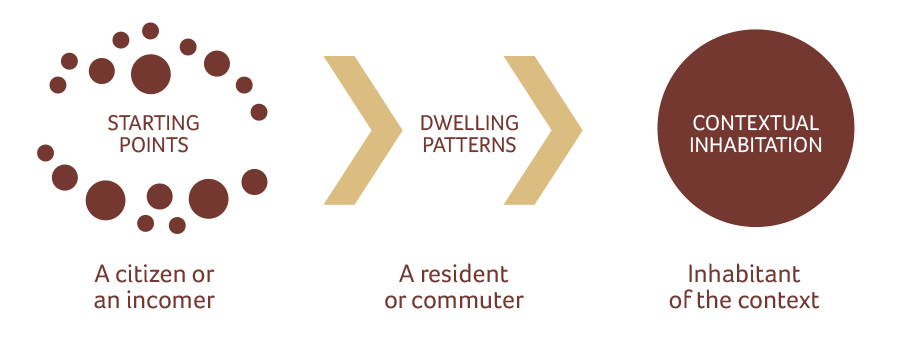

In this article I will explore how pioneer practitioners and those who support them can gain a better understanding of the timescales, resources and expectations needed to engage in a contextual approach to growing new disciples. By focusing on the “where”, the “starting points” and “dwelling patterns” of inhabitation, I will show how the life cycles of new Christian communities can be better understood and offer a deeper understanding of the pioneer “charism”: the character, influence and gift of a pioneer. I will begin by looking at a process I have termed “contextual inhabitation” before outlining how this can bring greater clarity in knowing where to start, the importance of encouraging partnerships and helping to manage appropriate expectations for practitioners and permission givers.

Defining “where”

There is an expanding catalogue of language, principles and methodologies that seek to describe the pioneer charism. Rather than seeing these as a blueprint, they are better employed as lens to explore “What are we noticing?” and “What is this telling us?” Although the Church of England has grown in its understanding of the “gift of not fitting in”, [1] there is still further to go.

It has the joint task of engaging with the discoveries of pioneers so far, as well as continuing to recognise, resource and release innovation on the margins. The major distinction that identifies the work of a pioneer is the “where”: a contextual, “go to” approach, with the intention of growing new forms of church in that space. This is achieved by engaging in a community in such a way as to be fully present among the people and the purpose of that place where pioneers are integrated, accepted and known: the journey of “contextual inhabitation”. Individual pioneers’ starting points and dwelling patterns vary but all should work towards becoming an inhabitant of their unique missional context. This may or may not involve physically living there as pioneers but it will be a process of continually responding to the changing cultural context. It’s helpful, therefore, to explore the “where” further, identifying the opportunities and challenges that different types of citizenship and residency can bring.

Starting points

Pioneers may be “incomers”, those who have no previous experience of the missional context, or “citizens”, those who have established networks and connections. These connections could be in the place where they live, in a work or social space or even within a digital community. As pioneers cross cultural boundaries, it is possible to be a citizen in one micro community while being an incomer in another, within the same wider community.

Dwelling patterns

Pioneers may be a “resident”, living within the geographical context, or a “commuter”, engaging with a context away from where they live. Four combinations of dwelling patterns that describe the process of contextual inhabitation and the “where” of the pioneer charism are possible:

Citizen Resident: a pioneer who has lived in their community for a period of time and has established networks and connections and who forms a new Christian community in that same context.

Citizen Commuter: a pioneer who works in a different context from the one in which they live and starts a new Christian community in that context.

Incomer Resident: a pioneer who moves into a context that is new to them and starts a new Christian community where they are living.

Incomer Commuter: a pioneer who lives in one context who starts a new Christian community in a neighbouring community.

Two key factors need to be considered in reaching contextual inhabitation: time and intention.

Time

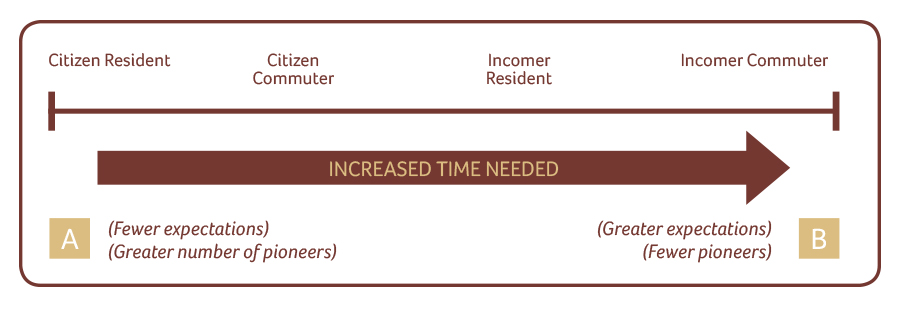

In my experience it takes between five and ten years to grow a new contextual Christian community to maturity. Different starting points and dwelling patterns will impact this development and different combinations will need varying timescales to inhabit and pioneer effectively. This will have an impact on the ways in which some pioneers are deployed and consequently the life cycle of the new Christian community (figure 1.2). Citizen residents may be able to grow something to maturity sooner as it’s likely they will already have been listening, loving/serving and possibly building community in that context even if they haven’t been conscious of the missional opportunities this could bring. Incomer commuters, however, will be starting from scratch, only present part of the time, and as such will need longer to inhabit the context.

Intention

Being a citizen, however, doesn’t mean that a new Christian community will necessarily emerge. There needs to be a clear intention to use citizenship in a missional and ecclesial capacity. This will involve prayerful listening, practical, servant-hearted engagement with the community, a desire to create spaces for faith to be shared and an intention for this to become a unique expression of church. Contextual inhabitation could also inform “when” to pioneer. By identifying contextual starting points and dwelling patterns, a deeper understanding of when to hold back and when to engage could emerge.

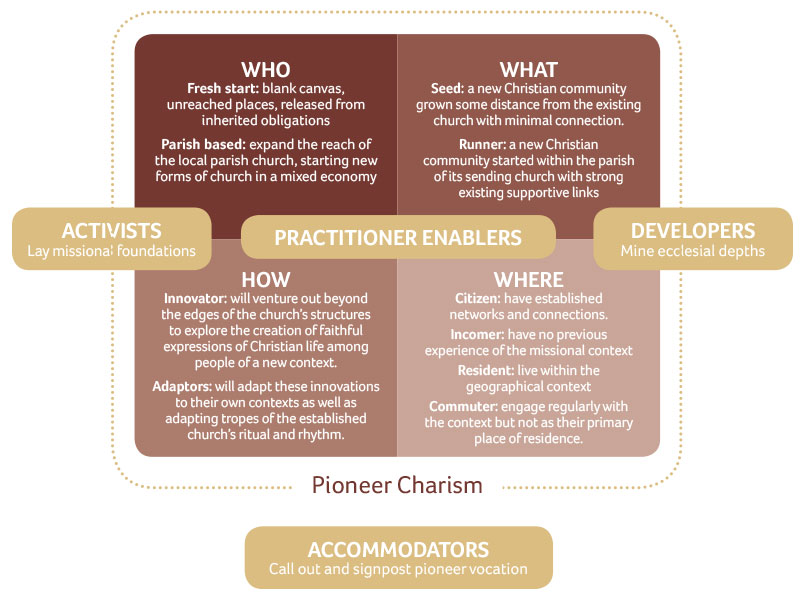

The pioneer charism

By engaging with the “where”, exploration of contextual inhabitation can bring a deeper understanding of the pioneer charism, as shown in figure 1.3. Pioneers may be called to be “parish-based” or “fresh start”, [2] they may start “seeds” or “runners” [3] and take the approach of an “adaptor” or “innovator”. [4] Pioneers will often have an apostolic ministry incorporating the role of evangelist and pastor and will embrace the prophetic and the role of teacher in different ways too. There is a growing recognition of the value of practitioners being enablers of indigenous leadership. “Community activists” [5] or entrepreneurs build missional relational foundations but may not necessarily initiate a new expression of church. “Developers” mine ecclesial depths in the early stages of the Christian community, often once the founding pioneer has moved on. Lastly there are those who oversee and support the work of pioneers. This includes “accommodators” [6] or advocates, who could be church leaders or permission givers, who are not necessarily pioneer practitioners but are able to call out pioneer vocation and make space for this to happen. All are valuable and all are needed.

These different elements of the pioneer charism can be seen in the example of Amy. Amy is a member of her local parish church and, encouraged by her vicar, she has started a café church in her village, which meets once a month. It’s reaching people who wouldn’t come to a traditional form of church, although some may come to the annual crib service in the parish church. With the help of her vicar acting as an accommodator, Amy is a parish-based pioneer, growing a “runner” by adapting the idea of café church for her context. She is a citizen resident living in the context where she is pioneering and as such has drawn on the relationships and connections she has already made. Her vicar is seeing the value of empowering those who are citizen residents in the community.

I will now turn to how introducing the “where” of the pioneer charism can bring further clarity, encourage partnerships and manage expectations.

Further clarity

By creating a framework and language for the “where” of the pioneer charism, permission-givers and practitioners can find further clarity and understanding. For example, if someone is a fresh-start, seed-growing, innovator, identifying as a citizen commuter will help them to know that their citizenship will give them a strong head start in the way they build community. As a commuter, they will need to focus strongly on becoming embedded into networks in the knowledge that they will have less opportunity than a resident to “bump into people”.

It is also true to say that the while the starting points and dwelling patterns will remain the same for some, for others this will change depending on their circumstances. While people may remain a resident or commuter, there will be an obvious journey, shown in figure 1.2, away from being an incomer [B] and towards becoming a citizen [A] as time progresses and missional relationships form. There may also be exceptions and nuances depending on the context.

Dan is a licenced pioneer and has recently moved into a first-stage development of new housing on the edge of a small market town as an incomer resident. He is a fresh-start pioneer, growing a seed, as an innovator. Being aware of this pioneer charism is helping him to know that it will take him a while to inhabit the context, as citizenship will take time to develop. This has proved to be useful for permissions givers to be aware of too, as they consider the resources that may be needed and set appropriate expectations for his ministry. However, he may inhabit the context faster than incomer residents in different situations, as shared experiences of moving in and developing community may help build relational networks quickly. Further to this, before he moved onto the estate, he worked with the new housing developers. By starting a new Christian community in the school, built before any housing, he began as a citizen commuter. Once he moved onto the housing estate, he kept elements of his citizenship with some while being seen as an incomer by others. This is helping him to discern the appropriate starting points and dwelling patterns to take and to manage his, and others’, expectations accordingly.

Encouraging partnerships

The presence of pioneer teams with different skills gathered for a common purpose is something to be explored further. Combinations of starting points and dwelling patterns could be combined to extend missional reach. It might be that a resident can complement a commuter in their absence and that a commuter can cross-pollinate as they move between contexts, or citizens could partner with incomers to inhabit the space together by sharing founding stories and co-creating local theology. When activists, developers, enablers and accommodators are added into the mix, a dynamic mixed economy team could emerge, each bringing a unique perspective to the other.

Managing expectations

The pioneer movement is made up of a wide range of different types of people: lay, ordained, paid, unpaid, full-time and those pioneering in their spare time. Further understanding of starting points and dwelling patterns could help to shape appropriate expectations for permission-givers and practitioners.

Firstly, renewed expectations could empower and value pioneers who already have the unique gift of citizenship. The Church of England has set a goal to double and double again the number of pioneers by 2027, anticipating that 80 per cent of these will be lay people. [7] “The Day of Small Things” research concluded that nearly half of those leading a fresh expression were lay pioneers, with a third of the total having no formal training or authorisation (the lay-lay). In addition to this, it found that a significant number of traditional/ inherited trained clergy, some in a post of responsibility, were leading a fresh expression of church. [8] In each of these examples there may be a greater likelihood of contextual inhabitation emerging through existing residency and established citizenship.

Karen is an ordained minister who has been living in her parish for a number of years and wants to connect with the unreached in her community in new ways. Acknowledging the value of her existing citizenship and residency through the community engagement as a parish priest has proven to be beneficial. It has shown her that she already has good foundations in exploring a contextual approach and has therefore inspired her to start a runner alongside the ministry of the inherited church.

Secondly, in order to grow the movement and raise up indigenous leadership, those inhabiting the pioneer charism should be encouraged to be local enablers of others as well as practitioners. This will particularly be the case for pioneers who are commuters or short-term incomer residents who can encourage those around them to discover the pioneer gift and bring greater sustainability to often fragile and emerging new Christian communities. The pioneer criteria in the Church of England looks for this quality within the collaborative criteria set. [9]

Thirdly, there is sometimes a concern that some pioneer posts don’t allow sufficient time for new Christian communities to grow from scratch. Licensed pioneers deployed to a new context often begin as incomers with greater expectations of missional growth and sustainability placed upon them over a fixed period of time, and yet will generally need more time to inhabit their context. Authorised or lay-lay pioneers, who are more likely to be citizens, generally have fewer expectations placed upon them and are given a more relaxed time frame when in reality it may not take them as long to inhabit their context. There is a misalignment here, which perhaps reveals an institutional model of ministry. Permission-givers may need to work alongside pioneers to think differently. For example, it might be that those in training for licensed ministry should be allowed to continue their journey of citizenship further into training or into posts of responsibility by remaining in the same context, as is happening in some dioceses.

Greater imagination may also be needed to explore other ways of supporting lay and ordained pioneers to allow contextual inhabitation to flourish. In doing so, a richer mixed economy of leadership could emerge where training and deployment strategies are more responsive, reflecting a wider spectrum of pioneer ministry.

Conclusion

Bringing together the who, what, how and where of the pioneer charism is valuable for all those engaging in a contextual approach and reveals a variety of ways this could be expressed. Exploration of contextual inhabitation adds a valuable dimension to this and can help to bring further clarity in understanding where pioneers should start, the importance of encouraging partnerships and helping to manage appropriate expectations for practitioners and permission-givers.

This could also have important implications in the way pioneers explore vocation and are trained and deployed. Recognition of the pioneer charism of those God is calling will give confidence to many more potential pioneers to grow new contextual Christian communities. This will take courage and commitment to think outside of the box, but, in doing so, could be a catalyst for the development of pioneer ministry into a new dimension.

About the author

Ed Olsworth-Peter is the national adviser for pioneer development for the Church of England. Working across dioceses and pioneer networks, his role is to develop an integrated vision, strategy and practice for pioneer ministry in the Church of England. He is a fresh expressions associate and a council member of the Archbishops’ College of Evangelists.

More from this issue

Notes

[1] Jonny Baker and Cathy Ross, eds., The Pioneer Gift: Explorations in Mission, (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2014).

[2] “Vocations to Pioneer Ministry,” The Church of England, accessed 3 October 2019, https://www.churchofengland.org/pioneering.

[3] George Lings, “The Day of Small Things,” Church Army’s Research Unit, November 2016, accessed 3 October 2019, https://churcharmy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/the-day-of-small-things.pdf.

[4] Tina Hodgett and Paul Bradbury, “Pioneering Mission is… a Spectrum,” Anvil 34:1 (2018), accessed 3 October 2019, https://churchmissionsociety.org/resources/pioneering-mission-spectrum-tina-hodgett-paul-bradbury-anvil-vol-34-issue-1.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Richard and Lori Passmore, Fresh Expressions and Pioneering in Cumbria (2018), 9.

[7] Ministry Division, “An Update on Resourcing Ministerial Education, and Increases in Vocations and Lay Ministries,” The Church of England, 2018, accessed 3 October 2019, https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/GS%20MISC%201190%20-%20An%20Update%20on%20Resourcing%20Ministerial%20Education%20and%20Increases%20in%20Vocations%20and%20Lay%20Ministries.pdf.

[8] “The Day of Small Things,” table 76, 177.

[9] Ministry Division, “Pioneer Criteria,” The Church of England, 2017, accessed 3 October 2019, https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/selection_criteria_for_pioneer_ministry.pdf