Anvil journal of theology and mission

It’s a new day: reflections from a practical theologian and artist in lockdown

by Chris Duffett

It was still dark when we set out but we had torches so that we could avoid the cowpats. While the walk up the mountain was familiar to us it was fairly steep, and the beams of our torches paved the way well for us up the twists and turns of the only mountain on Bardsey Island.

We wouldn’t need the torchlight on our return as our goal was to catch the dawn and simply sit and watch it. To be. There was no agenda despite my role as chaplain on the island for the week, so I had gently reassured my “two-metres-apart” sunrise-seeking companions that we were just going to gaze at the magic rather than have a prayer time or service.

We sat on black plastic bags so that we wouldn’t get soggy bottoms. The swishing of the plastic was the only sound in the wind as we patiently waited in the dark. Our eagerness had made us early and we had a long wait until the first glimmers of light appeared on the east, and then shards of Naples yellow and gold intermingled with blue and grey danced its way to us. We sat in awe as the rustle of plastic was joined with a growing chorus of birdsong.

Watching the sun rise when I served as chaplain on the island of Bardsey made a deep impression on me. On the way down one of the sunrise pilgrims asked if I had done any painting on the island as I usually do. I explained that I hadn’t as I had struggled to paint anything over the week. Twenty-four hours after this conversation, I had done 11 sunrise paintings. I felt like the sunrise-watching was like the archetypal dodgy kebab. The experience kept repeating on me and I couldn’t stop coming back to that place of watching in awe. Paintings flowed and the subsequent weeks after, when in my studio, nothing but abstract scenes of dawns flowed from me as I worshipped and prayed and took time to paint for the sheer joy of painting rather than the hurried finishing of a commission in time for a birthday or Christmas present.

As I painted, I prayed over and over: “It’s a new day.” It felt like the paint and scenes captured hope for tomorrow. The dawn scenes that flowed, I believe, began to represent the liminality that many of us now find ourselves in. We don’t know what lies ahead and we find ourselves in a foreign and alien COVID land feeling like church exiles who are not sure of the way home. The dawn pictures that I couldn’t stop painting simply declared a new day that, while it yet can’t quite be seen, is inevitable. God brings hope as sure as there is a new day tomorrow; dawn is a promise of a whole new day.

Reflecting on my experience has led me to see once more the vital role art has in revealing big truths in simple ways. At university I studied art and theology as two separate disciplines, but many years later, as I co-principal The Light College and train pioneers and evangelists all over the UK, art and theology have become intertwined and somewhat inseparable. I teach our students how to apply the big truths of the gospel in creative ways that contextualise the message for a post-Christian culture so that they too may connect with and get what the good news of Jesus is all about. Theology and art I believe isn’t a “one or the other” but rather two expressions of the study and experience of God: art illustrating and illuminating deep theological truths and theology bringing form and narrative to prophetic abstract scenes.

Since that time on the mountain, there are three lessons I have learned between this interplay between art and theology that I would like to share with you.

1. Art is the child that leads me by the hand into the depths of the Kingdom

When I paint it is playful and innocent, but conversely the deepest theological treatises seem to be written with a stroke of a brush or penned with flowing inks. Jesus tells us, “Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.”1 I have yet to meet a child who can’t paint. “Do you paint?” I always ask as people gather to watch what I am doing when I paint prayers in public. An overly caricatured response to this question is that children always say, “Yes, and I’m brilliant at it,” while adults always say, “Oh no, no, no, I don’t have a creative bone in my body!”

The innate ability of children to create is the childlike faith I exercise when I paint; not sure whether what I do will go well or not, I simply trust and go with the flow. As the late educational psychologist Sir Ken Robinson once put it, if we’re not prepared to be wrong, we will never come up with anything original. As I paint, I need to be prepared to make mistakes so that the original creativity and childlike images can flow. Daring to do this brings me into a place of happenstance with God that I can only describe by using the Hebrew word paga, which is to encounter him and in so doing make intercession.

One example of painting deep theological truths was the result of three incidents that inspired me as I felt God speak through them. The first was seeing a picture of wild geese on a friend’s Facebook page. The second was a “breath prayer” by writer and broadcaster Sheridan Voysey, encouraging people for their wellbeing to breathe in the gifts of the spirit and breathe out the opposite. Thirdly, while on a prayer walk a flock of wild geese flew over me and as they did I considered the ancient Celtic symbol of the Holy Spirit, the wild goose. To respond theologically and creatively to these three occurrences created a kairos moment for me for which I painted nine wild geese representing the fruit of the Spirit with his nine life-giving characteristics. I made the image into some simple prints and over eight weeks gave away via the internet just shy of a thousand of them to those who wanted to keep one and give two away. This simple image resonated with people in ways that I couldn’t have imagined, and God spoke through it and the accompanying prayer to help people through the pandemic as they faced uncertainty, loss and fear.

2. Art is the prophetic voice that helps me speak gently of what is to come

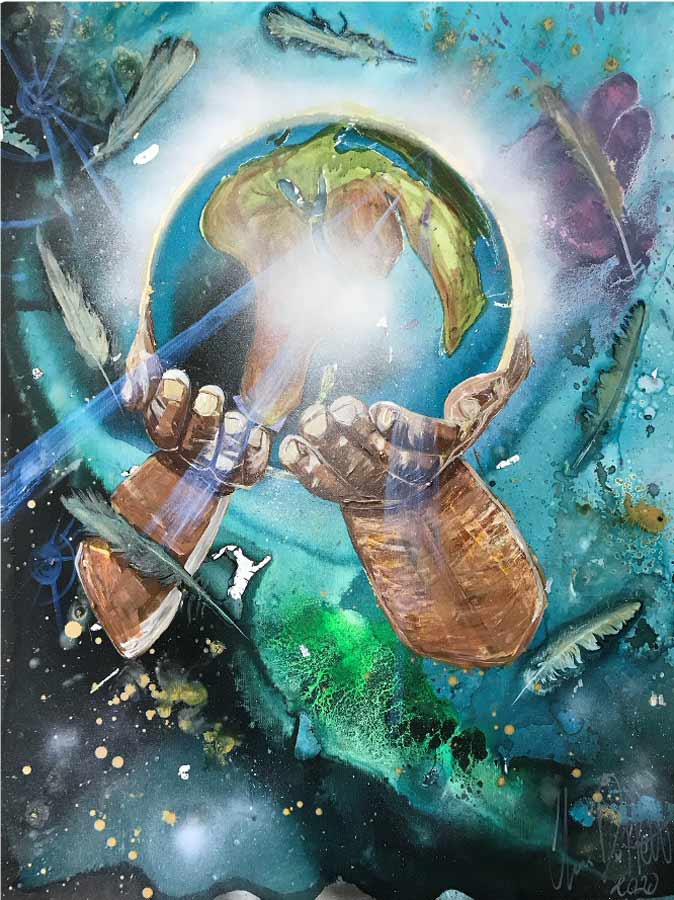

Months before our first national lockdown I painted large cosmic scenes with hands in them; while being painfully aware of how such an image could be perceived as Christian cheese, I was compelled for weeks to paint scenes of Jesus holding the world. It felt some kind of prophetic “pamphlet”, only rather than being shown through pages and words, it was shown by a simple painting with a simple message that despite the pain and uncertainty, Jesus has got this. Despite this virus, he is Lord. Despite loss and damage, he is Lord.

This image has brought reassurance to many as I shared the image on social media platforms and magazines, and offered it as a free print for people to give away and remind others of the simplicity that Jesus holds this world in his hands.

3. Art is a signpost to both the transcendence and imminence of God

When I look at a piece of artwork, it is often easy for me to see the beauty and power of the Creator God. Of course, not all art does this. Not all art brings glory to God, but it’s surprising how much does, even when the artist’s intention may not be with that in mind.

With my artwork I long that it speaks of the nearness and earthiness of God with us: God incarnate, made flesh, who loves to rub shoulders with all people and remind them that they are not alone and that they are known and loved. In normal times this kind of painting would be done in places like pubs and cafes, where I find I’m in my element as an evangelist and artist, creating something simple through paint for people to know that they are loved.

Notwithstanding that as I write this article pubs and cafes are closed, how can art show and tell good news to people in a time of social distancing? I was fascinated to read an article by an old friend, church leader Esther Prior, who wrote: “I am passionate about creating ‘sacred spaces’ outside – I call it ‘ministry to those who pass by’. I think there are lots of people who are searching, who even have ‘spiritual’ thoughts but are nowhere near being ready to engage with Christians or with a Church in any overt way. So we use art to proclaim the gospel without words, hoping to draw out those who might one day want a conversation about it all.”2

I have taken every opportunity I have had in this strange season to offer simple prints to those who deliver parcels and visit our house, or people I non-literally bump into at two metres apart at the post office. This prompts questions and opens up opportunities to offer gospel words that accompany images of good news.

Lastly, I dare you to do two things: How could you show some art that would gently introduce people who pass by your home or church building something of the majesty and closeness of God?

How could you create something to give away to someone who needs to know that they are known and loved by God?

I would love to see what you dare to do!

About the author

Chris Duffett, from the Light College, is an artist with a desire to bring words, comfort and scenes from God’s heart to those he paints for. Chris’s fine art seeks to bring the colours and mystery of other realms. Chris studied art with theology at Chester College and has exhibited in Chester and Cambridge and worked as an artist in residence with Chelmsley Wood Baptist Church. His work is often used for publications and magazines. As well as painting and creating he is the founding evangelist of The Light Project, an author, tutor, poet and Baptist minister.

More from this issue

Notes

1 Mark 10:15 (NRSV).

2 Esther Prior, “Guest Post: Coming to grips with a COVID Christmas,” IVP Books Blog, 16 October 2020, https://ivpbooks.com/blog/guestpost-coming-to-grips-with-a-covid-christmas.html.