Anvil journal of theology and mission

Mission and disabled people

by Tim Rourke

In 2013 I attended a course called Self-Management of Long-Term Health Conditions. There were people on the course who lived with a range of different impairments, from Parkinson’s disease to spinal conditions and ME. We had different conditions but shared many of the same experiences of living as disabled people in the UK today.

Having shared with the group a prayer activity that I use on my bad days, a discussion about church began. I discovered that since we received our various diagnoses, every member of the group had been to a church. Twelve people searching for help in a time of hurt and pain had tried to connect with God through various Christian communities. I also discovered that from that group, I was the only person still going! As a disabled evangelist this shocked me and made me wonder why, and what can we as disabled and non-disabled Christians do about it?

According to the research we carried out in the Derby diocese in 2020, an estimated 11 per cent of church members are disabled, using the definition of disability from the Equalities Act 2010.1 This compared to a national average of 15 to 20 per cent in the general public and over 40 per cent for 65-year-olds.

Interestingly the number of common adaptations made to a church building did not directly correlate with the number of disabled people in any given church. On reflection, the Disability Inclusion Working Group (Derby Diocese) felt that adaptability and willingness to listen to disabled people’s stories increased the likelihood of them being a part of a church community. Disabled people in decision-making bodies and leadership were also fairly uncommon.

Disabled people are among the most isolated groups in UK society. Sixty-seven per cent of people feel uncomfortable when talking to a disabled person (according to a report by SCOPE in 2014).2 Disabled people are more than four times as likely to feel lonely, “often or always”, and more than twice as likely as to experience domestic abuse than non-disabled people.3

This potentially has huge implications for disabled people and the church’s mission and evangelism across the UK.

Often churches aim to grow through engagement with people we meet through social interactions outreach and connecting with our communities. As disabled people are often find themselves excluded by those communities and beyond the edges of society, these methods will struggle to engage.

Pioneering among groups who are not engaged with the church might prove more successful, one might think. However, because these communities congregate around pre-existing groups, there is a need to consciously reflect on how many disabled people live in these groups to begin with. In my experience meeting with pioneers, this is rarely done.

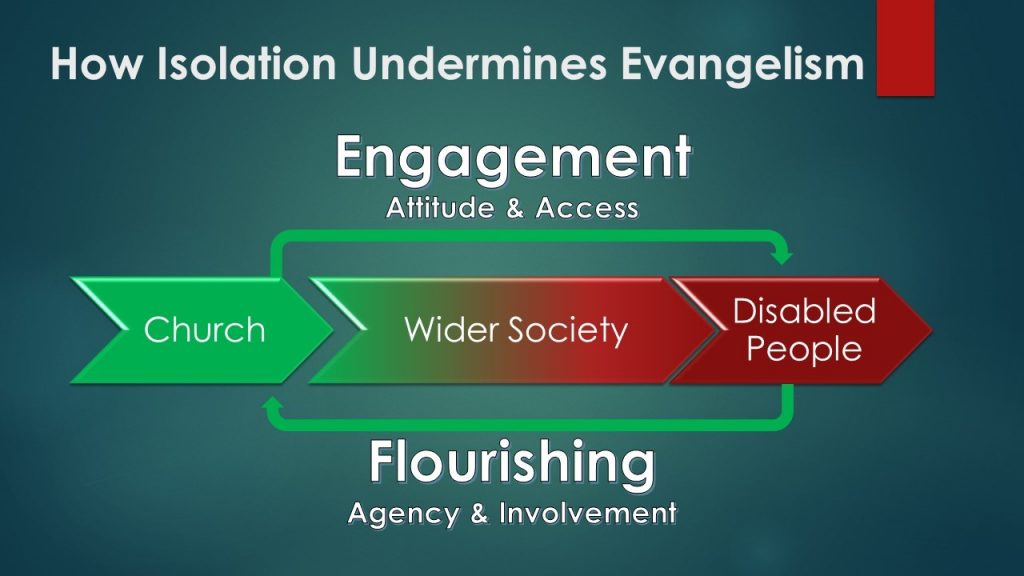

The diagram highlights some of these challenges. The church (in green) tries to influence and encourage people in the wider society to respond to Christ, but it is more likely to meet people who are from “easy-to-reach” groups. “Harder-to-reach” groups, in this case disabled people, need to be engaged with in specific and intentional ways.

At the same time, disabled people who are already within the church need to be seen as important, valued and flourishing. Christianity needs to be Good News to them, and listening to their experiences needs to inform and shape the engagement for the future.

Over the course of a year, a team of disabled Christians from churches across the Diocese of Derby looked into ways that church structures and local churches can engage with disabled people and become more receptive to their needs. Together we wrote a report called “The Disabling Church… and what to do about it”. At Diocesan Synod in October 2021 the report was received and these three challenges for the diocese were accepted:

Aim 1

(Attitudes) to challenge and change all attitudes that limit the lives of disabled people in our churches and structures

Aim 2

(Access) to remove all barriers that stop disabled people engaging with church, both online and in our buildings

Aim 3

(Agency) to celebrate the lives of all disabled people and provide space for them to minister alongside others in response to God’s love During the year of the project, we saw examples of how churches can build bridges and barriers to disabled people and how, with small changes, disabled people can be included better.

Attitude

Challenging the assumptions and attitudes of a community is the most influential way for inclusion to take place. Churches, like all communities, have set ways of operating that are often not reflected upon or written down. These were probably not shaped by disabled people and therefore don’t often accommodate disabled people who need to do things in a variety of different ways.

Christians also have quite a history of making judgements of disabled people and using inappropriate methods of prayer. The experiences have damaged many in the disabled community. Most visibly disabled people have at least one story of being singled out for prayer, often without their consent. This makes the church a challenging place to engage with in the first place.

However, with a flexibility and a willingness to listen, simple changes can build bridges instead. In one example, a church had an unusual way of reading the psalms antiphonally between the reader and the congregation. It was joined by an older teenager with learning disabilities who asked to read in the service. The church changed its practice immediately to only have one response at the end of the reading, so that he could be included!

Access

Often the barrier to thinking about access is that we have many old buildings and few funds to make them accessible, with ramps, toilets and hearing loops costing money that we don’t have.

However, there are things that can be done very cheaply. For example, including photos and a description of your building on your website so that people know what they will face when they enter enables people to plan their way in before they arrive. Also, make sure the signs in your buildings are clear, readable and correct.

If you can’t do everything (and you probably can’t), then do something! Get advice from organisations or advisors, or even better, invite a group of local disabled people into your church and ask them what would be most useful for them to know so that they can get around in your building. You have experts locally, so use them.

And please stop saying “everyone welcome” on your posters! While you are probably open to anyone who wants to come, that doesn’t help disabled people know if or how they can come. There is little more demoralising than turning up to discover that the event that everyone is welcome but that can’t include you!

In Derbyshire, a new church group was forming around the joy of nature and meeting God while spending time outside. The group knew that the planned walk was flat. In the first session, a scooter user came along to test it. Now all the publicity says “wheelchair accessible”. Knowing things in advance helps disabled people to know that they are “welcome” too!

Agency

Representation of disabled people in the leadership of the Church of England is hard to judge. As far as I am aware, no bishop has stated that they are disabled, although by the definition used in the Equality Act and the age profile of bishops, they probably are.

Disabled people often face extra challenges to other forms of ordained or lay leadership, and because they are disabled, they may never be given the opportunities to serve in the first place. This lack of involvement leads to sidelining and othering of disabled people. This is often seen when our intercessions pray for the ill and the sick as them, rather than us.

A pioneer Christian community were writing their prayers and liturgy, which included disabled people. Disabled people were involved in the creation of the prayers, which affirmed everyone as they were and encouraged everyone to respond to God’s call. The “us and them” prayers that churches often use didn’t need changing or adapting, because they were never written in the first place. Involvement of disabled people in all we do in our churches informs our inclusion more than anything else.

So, what is Jesus’ Good News for those people on the “long-term health conditions” course who joined and then left the church?

Maybe it is to be loved as they are. To be listened to as they are. To be included as they are!

Not because God will take away their symptoms and conditions (a cure) to make them acceptable to others, but because in the church, the disabled and resurrected body of Christ, together we can find hope, peace, love, healing and belonging.

About the author

Tim Rourke is a disabled Church Army evangelist developing a pioneering community with others in Chesterfield in Derbyshire. The community consists of three groups: disabled adults, disabled children and carers. For the last two years, Tim has been leading a disability inclusion project to produce a report to help disabled people to flourish and be accepted better across Derby diocese. He is studying for an MA in Theology and Transformative Practice at The Queens Foundation, focusing on the experiences of disabled people. Tim’s hobbies include playing board games, cooking and watching sport.

More from this issue

Notes

1 You’re a disabled person under the Equality Act 2010 if you have a physical or mental impairment that has a “substantial” and “long-term” negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities. “Definition of disability under the Equality Act 2010,” GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/definition-of-disability-under-equality-act-2010.

2 “Brits feel uncomfortable with disabled people,” SCOPE, 8 May 2014, https://www.scope.org.uk/media/press-releases/brits-feel-uncomfortable-with-disabled-people/.

3 “Outcomes for disabled people in the UK: 2020,” Office for National Statistics, 18 February 2021, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/outcomesfordisabledpeopleintheuk/2020.