Anvil journal of theology and mission

Theology at the borders of psychosis: transcendence of the artificial borders of sanity, ableism and the implications for practical ministry

by Rachel Noël with Fiona MacMillan

Introduction

Implicit in theology is the expectation that the author is “sane”. In Western society there is a widespread labelling of “madness” that serves to isolate and separate perceived “mad” voices from the so-called “serious” work of theology.

Drawing on my own lived experience of psychosis, this article takes the work of Catherine Keller into conversation with Isabel Clarke’s work on psychosis, spirituality and madness in order to examine and critique the borders between psychosis and spirituality. Keller articulates a theology from the deep, that has to learn “to bear with its own chaos”,1 while Clarke links the highest realms of human consciousness and the depths of madness, challenging the primacy of rationality and encouraging a paradigm shift in how we view the (often perceived hard) borders between psychosis and spirituality. This article draws together the themes of chaos, depth and the transliminal state of psychosis to redeem the voice of madness in theology and to dispute the borderland between psychosis and spirituality.

In this article, I will go on to explore what implications this may have in our practical ministry, connecting with themes of shame, ableism, disability theology and art.

Theology at the borders of psychosis: transcendence of the artificial borders of sanity2

Why is this important?

Public Health England states: “Psychosis is characterised by hallucinations, delusions and a disturbed relationship with reality” and states that “psychosis is one of the most life-impacting conditions in healthcare”.3 Six per cent of the UK population says they have experienced at least one symptom of psychosis.4 Those diagnosed with severe mental illness such as psychosis die on average 15 to 20 years earlier than the general population.5

Joanna Collicutt states that:

While premodern culture had little difficulty in accommodating divine madness, tolerating a blurred boundary between madness and religiosity, the rise of modern psychiatry has rendered this problematic. Following on from the Enlightenment, public discourse has located madness firmly in the mind of the individual, conceiving it as a kind of sickness – a “mental health” issue. It is not considered appropriate or enlightened to describe people with psychosis simply as “strange”; it is more usual to describe them as “very unwell”.6

This individual model of mental illness is connected with the medical model of disability and although we’re starting to view disability through the social model lens,7 there remain aspects of mental health that often still seem to be regarded outside of this model: in particular, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar and borderline personality. These conditions seem to invoke fear. They challenge our desire for predictability and control.

Peter Kinderman is professor of clinical psychology at the University of Liverpool and is leading work challenging this. He writes:

Traditional thinking about mental health care is profoundly flawed, and radical remedies are required.… We must move away from the “disease model”, which assumes that emotional distress is merely a symptom of biological illness, and instead embrace a psychological and social approach to mental health and well-being that recognises our essential and shared humanity.8

He describes his work as “a manifesto for an entirely new approach to psychiatric care; one that truly offers care rather than coercion, therapy rather than medication, and a return to the common-sense appreciation that distress is usually an understandable reaction to life’s challenges”.9

According to French psychoanalyst Lacan, psychotic thought has a high degree of freedom, but by not conforming to accepted standards of thought, it is therefore not capable of being part of religious discourse. The Royal College of Psychiatrists states that “while psychosis is at the heart of psychiatry, psychiatrists have often dismissed or regarded with distrust the spirituality that is valued by many of their patients”.10

As a church leader, I’m teaching people how to consciously enter the transliminal, through the experiences of stilling and centring the mind

In 1999, the Royal College of Psychiatrists Spirituality Special Interest Group was initiated. Isabel Clarke has edited two editions of their work on psychosis and spirituality. There exist deeply culture-bound limitations of how we conceive and describe psychosis and spirituality. She writes, “Boyce-Tillmann discusses the tendency of cultures to favour either this, intuitive and spiritual or the more scientific and logical style of discourse as the existence of a dominant and a subjugated way of knowing.”11

Anthropologist Natalie Tobert explores the ways different cultures have different ways of articulating and valuing these experiences, including shamans and mediums who claim to go between the worlds, and those who describe out-of-body experiences and near-death experiences.12 By contrast, in the West, “Warner notes that in societies where experience of the spiritual/psychotic realm is valued, people diagnosed with schizophrenia have a far better prognosis than in modern Western society.”13

There have been various models developed to try to account or describe the different ways of knowing that are encountered. As ever, language starts to get tricky, and our human desire to want to categorise and define neat boundaries is challenged. Most models use terminology that explicitly “incorporates a distinction between the psychotic and the spiritual, and so impedes discussion of the common state” that Clarke argues underlies both.14 Much of this language includes positive or negative connotations, assumptions deeply embedded in the descriptive words. A hierarchy of experience is embedded in the language we choose. Moreover, we are talking about individual, subjective experiences, during different states of experience that make this inaccessible to objective study.15 “Psychoanalysts talk of the emergence of un- or subconscious contents into consciousness… The downward spatial metaphor implies inferiority. Words such as spiritual and mystical, with wholly positive connotations, tend to exclude anything dark or pathological.”16

Clarke “starts from the recognition of two possible modes in which a human being can encounter their environment. The most normally accessible of these two modes can be described as ordinary consciousness. The other mode is a less focused state in which both psychotic and spiritual experience becomes possible, as well as being the source of creativity and personal growth.”17 She describes this as transliminal, following psychology professor Gordon Claridge Gordon Claridge – the echoes of threshold – to distinguish between transliminal and everyday functioning. Clarke suggests that following on from this, “it does appear that transliminal experience is mediated by a loosening of boundaries and greater connectedness within the brain, whereas focused cognition relies on inhibition of extraneous influences”.18 While we might want to see psychosis and spirituality as two very discrete, separate, neat categories, everyday functioning and transliminal functioning are both states that we all have some experience of. In sleep, we naturally enter deeply into the transliminal.

As a church leader, I’m teaching people how to consciously enter the transliminal, through the experiences of stilling and centring the mind, contemplative prayer and meditation. This is part of our tradition and practice. Simone Weil says that “absolutely unmixed attention is prayer”.19 We see this in Buddhist practice, in hypnotherapy, in mindfulness; there are so many ways that people are seeking to access the transliminal.

Transliminal space is a place of paradox; it’s “both/and”. However, it seems that there is a really strong desire for professionals (both psychiatric and clerical) to want to categorise – to be able to name an experience as either psychotic/breakdown/disorder or as spiritual/religious experience. Why do we need to do this? Clarke argues that this “absolute distinction is invalid and essentially meaningless”.20 Moreover, I would argue that seeking to enforce this distinction is, in fact, dangerous.

Why would we want to seek to categorise someone else’s meaning-making as either spiritual or as disorder, and to enforce the separation of these?

Karen O’Donnell, in her work on trauma theology,21 speaks of the importance of meaning-making, of narrating our own story. For example, when we talk about Black theology, about trans theology, there is an importance of these voices not being narrated, defined and enforced by others. People need to be able to tell their own stories and develop their own meaning.

Why would we want to seek to categorise someone else’s meaning-making as either spiritual or as disorder, and to enforce the separation of these? In doing so, frequently the meaning-making is disrupted/corrected/ deemed so dangerous that it needs to be sedated/ numbed/silenced. The naming and labelling of these experiences by others can be part of the creation of trauma.

Defining with big disorder labels brings with it questions of medication (often by coercion), of shame, of hiding. Assumptions that there is nothing of value, no “truth”, nothing of meaning within what has been experienced when it’s classed as disorder. This is ableism. “Ableism is a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other.”22

In society we hear that many people on the edge are having to justify their voice, their experience. I would argue that those experiencing psychosis, psychotic disorders, are still being taught to deny their experiences, to reject their experiences, to suppress and numb them; they are being medicated and silenced, and we’re still questioning whether their voices are even valid.

My story

It is helpful if I explain why this is so important to me. I’m an Anglican priest. I spent part of my curacy in psychiatric hospital. Not as a chaplain, but detained under the Mental Health Act. I was sectioned. I experienced mania and psychosis in reaction to a medication. Within the depth of these experiences, I also encountered the most profound spiritual experiences too, of peace beyond all understanding. Repeated experiences of deep unity and connection, of awe and wonder; alongside the fear and disorientation, the pain of psychosis. I lived in both/ and space. Soon after one week in hospital I was labelled with bipolar disorder, with ADHD, with sensory processing disorder, and suspected autism (later confirmed). Lots of labels, that come with judgements on how I perceive the world, on how I process information, and on how I communicate.

My voice became “othered”: one that couldn’t be trusted by other professionals – medics, clergy. I was labelled heretical. Clergy wanting to pray to cast out demons (for future reference, if this ever happens to you, whatever response you give gets categorised as further “proof” of demons). Senior church leaders deciding if it was possible to be a priest with any of these labels or experiences, let alone all of them. I was told that I shouldn’t speak publicly of my experiences, of my labels. That it would be better if I were silent. That it would be better if I went elsewhere.

In my openness, I have encountered many others who have been excluded from churches, from religious communities, who have been forced to accept priests naming them as heretics, naming their experiences as all illness, naming the depth of their experience of God, of other, of deep connection as so wrong, as so ill, that it is dangerous. Of no longer speaking of their experience, of others abusing their power by defining, closing down and silencing their stories. Of living with the shame, the trauma.23

As a priest, as a theologian, in the West, where do I go with this?

Keller and theology of becoming

I’m going to take this into conversation with Catherine Keller, and the first few verses of Genesis. In her book The Face of the Deep, she presents the case that most orthodox theology has assumed as “fact” the idea of creatio ex nihilo. Keller argues that this doctrine, of creatio ex nihilo, has developed as a preferred dogma in Western theology, as a way of keeping theology consistent in what it is rejecting, in what it’s labelling as scandalous, heretical and demonic.

In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light.

Gen. 1:1–3 (NRSV)

She suggests that Western tradition prefers to jump from verse 1 to verse 3, from the beginning with God, to the divine speech “let there be light”, choosing to see God working against the formless void that’s in between. In this work, Keller focuses on the first two verses of Genesis, and throughout the book she is articulating a theology from the deep, from the chaos, tehom. She says, “It refuses to appear as nothing, as vacuum, as mere absence highlighting the Presence of the Creator, as nonentity limning all the created entities. It gapes open in the text: ‘and the earth was tohu vabohu, and darkness was upon the face of tehom and the ruach elohim was vibrating upon the face of the mayim.’”24

Just as with Clarke, for Keller the nuance of words is deeply significant. Keller’s book is in four parts. Part 1 sets out the continual contrast between a theology of the deep (tehom) as opposed to the Creator/creation theology with God as the Lord and owner of the world (dominology)25 – suggesting that this dominology brings with it a “loathing of the deep” and leads to the desire to master chaos, to control the “origin” (perhaps setting up theologically a deep fear of the perceived chaos or lack of control of psychosis). Keller suggests that Irenaeus first set up the virtual elimination of tehom, with his critique of the gnostic usage of the term. She goes on to highlight Athanasius’s understanding of eternity, power and nature, that plays out in denial of difference, in purity of culture. Keller identifies Athanasius as displaying a homophobia, that’s paired with tehomophobia.26 She finds a similar ambivalence to tehom in Augustine too.

And while Karl Barth does reject creatio ex nihilo as unbiblical, his understanding of God still leads to a very strong Christian dominology. Describing Genesis 1:2, Barth says “this verse has always constituted a particular crux interpretum – one of the most difficult in the whole Bible”. For Barth, “deep is not nothing, but worse than nothing”.27 For Barth, God is creating not from the nothing, but against the nothingness… which is the chaos.

Deeply embedded in so much of our theology is a profound fear of the chaos, of the deep.

I suggest that witnessing psychosis plays into this fear and is why there is quite such a strong desire in so many to distinguish between psychotic and spiritual experience, to see them as separate and distinctive. This is to silence, remove or eliminate the voice of chaos from the purity of spirituality, of theology that many hope for.

Keller reminds us that “creation is not a beast to be tamed, but a deep mystery – a mystery that we experience the echo of in our own times of chaos and deepest prayer, and over which the ‘wind from God’, the ruach elohim, ‘vibrates’. We are, in our most primordial reality, vulnerable creatures of this earth in which the ‘formless void and darkness’ from time to time reasserts itself.”28 In Keller’s articulation of mystery, of chaos, of the depth of prayer within that, there is a theology that has to learn to bear with its own chaos, a theology in which there is space for voices from the transliminal states.

What difference might it make to our shared life as the body of Christ if we were to let this theology shape our worship, our ministry and mission together, our pastoral care?

Creation theology and ableism29

The dominant creatio ex nihilo theology has shaped so much of our thinking, our liturgy, our art. In our creation stories, we find Adam and Eve. These are almost always portrayed as able-bodied, idealised, “perfect” beings.

For example, the beautifully constructed creation of Adam, by Michelangelo. Clearly placed colours and forms, everything in its place, directed exactly by God.

Genesis 1:

So God created humanity in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.30

Genesis 2:

Adam and his wife were both naked, and they felt no shame.31

These first people were at home with each other and with God.

With no shame

Eve and Adam, the apple, the Fall. We’re told that this is where pain comes in for the woman. Pain becomes associated with theology of the Fall. There enters the language of brokenness.

And shame.

Brene Brown describes shame as being “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love, belonging, and connection.… Shame thrives on secrecy, silence, and judgment.”32 Judith Rossall writes more about this in her book Forbidden Fruit and Fig Leaves, saying: “If shame is intimately linked with our sense of how others see us, then it is even more intimately linked with a fear of exposure. For many of us our greatest fear is that if our real naked self is seen, then we might be rejected.”33

Paintings of creation don’t seem to show pain, or differently shaped bodies, or different ways of being. Adam and Eve are a bit like the original Ken and Barbie, or the Photoshopped images in magazines.

Disability theology as a liberation theology challenges these very starting points. Shane Clifton points out that:

If creation is good, as Genesis 1 repeatedly claims, then disability is good.… [The] same life-giving processes also generate disability. The paradox of life is that potency and vulnerability go together. And because this is so, far from being a consequence of sin, disability is a good, a symbol of potent, creative, beauty, a testimony to the generativity and limits of nature.… Just as God is wholly other, the divine image is not captured in the ideal of a singular “manly” reasoned perfection, but in the vulnerable untamed chaotic potent limits of disabled bodies.34

Ableism becomes both implicit and explicit in our language, in our art, in our liturgy, in the hymns that we sing – embedding the deep belief that able is superior, that living without mental illness is superior, and reinforcing the prejudice that disabled people require fixing, that their voices should not be heard unless or until they meet our definition of “well”. Entwining ableism in our liturgy creates and reinforces a sense of shame.

June Boyce-Tillman talks about the language of liturgy and says: “We need to work hard at a change of attitudes: ‘[It may] involve learning new skills and expanding the meaning of concepts, often “unlearning” what was formerly believed to be true.’”35 This is costly for our churches; it could mean new songs, new books, challenging the use of treasured hymns. It means being uncomfortable, noticing where we silence, where we discount, where we exclude. This isn’t something that can be tackled with lip service. Are we willing, individually and collectively, to let this sink in?

One of the particular challenges is that ableism is often disguised within the best of intentions. Boyce-Tillman describes how:

Disabled people came to be viewed as “worthy poor”, as opposed to work-shy “unworthy poor”, and given Poor Law Relief (a place in the Workhouse or money from public funds). Disabled people also became more and more dependent on the medical profession for cures, treatments and benefits and were shut away. Separate special schools and daycentres were set up that denied disabled and nondisabled people the day-to-day experience of living and growing up together.36

This was done out of “good intentions”. Christian institutions set up, churches supporting, seeking to do good. Able-bodied people making decisions, seeking to help, to fix; accidentally othering disabled people, seeing those with mental illness only as the objects of charity, the recipients of care, people to be done to, the vulnerable, the weak, expected to lead life as passive victims.

Are we really willing to treat all people as valuable in God’s sight, as beloved children of God, as individuals where the Spirit is already at work, whose story may open up to us more of God’s love and work?

Revelation 21:4, “[God] will wipe every tear from their eyes,”37 has led to an idea of a disability-free afterlife, because disability is unworthy and linked with sin. The idea of disability needing to be healed is another source for the marginalisation of disabled people in this world, but Christ is resurrected with wounds. In his book The Bible, Disability, and the Church, Biblical scholar Amos Yong writes:

[E]ach person with disability, no matter how serious, severe, or even profound, contributes something essential to and for the body, through the presence and activity of the Spirit; people with disabilities are therefore ministers empowered by the Spirit of God, each in his or her own specific way, rather than merely recipients of the ministries of nondisabled people.… [P]eople with disabilities become the paradigm for embodying the power of God and manifesting the divine glory.38

Paul describes a “theology of weakness” – in which qualities that are normally devalued, such as “foolishness, frailty, fragility, and vulnerability” are marks of how God empowers his people. Paul tells us, “‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness.’ So, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may dwell in me. Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities for the sake of Christ; for whenever I am weak, then I am strong.”39

Jesus starts his teaching in Matthew’s Gospel with the words, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”40 In Acts 2:17 we read, “Pour out my Spirit upon all flesh.”41 All people, not just some, not just those deemed worthy, not just those whose minds work in particular ways. All flesh includes all minds.

God’s Spirit blows through all of us.

I wonder if we are willing to accept that this is true even when someone is experiencing psychosis?

In his book, Incarnational Ministry: Being with the Church, Sam Wells articulates a theology of “being with”, arguing that the heart of Christian faith is God’s commitment to be with, revealed most deeply through Jesus. For Wells, being with starts with people’s assets, not their deficits, and models enjoying people for their own sake, not to “do for” them, or to “use” them.42

This can be really uncomfortable. Are we really willing to treat all people as valuable in God’s sight, as beloved children of God, as individuals where the Spirit is already at work, whose story may open up to us more of God’s love and work? Brene Brown describes true belonging as “the spiritual practice of believing in and belonging to yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.”43

Are we willing for our churches to be places where it is safe for people to share their most authentic selves with us? If we accept this, how might this challenge our worship, our choices of stories that we hear, of voices that we allow to lead? What might this mean for our pastoral care, for our intercessions, our prayers for people?

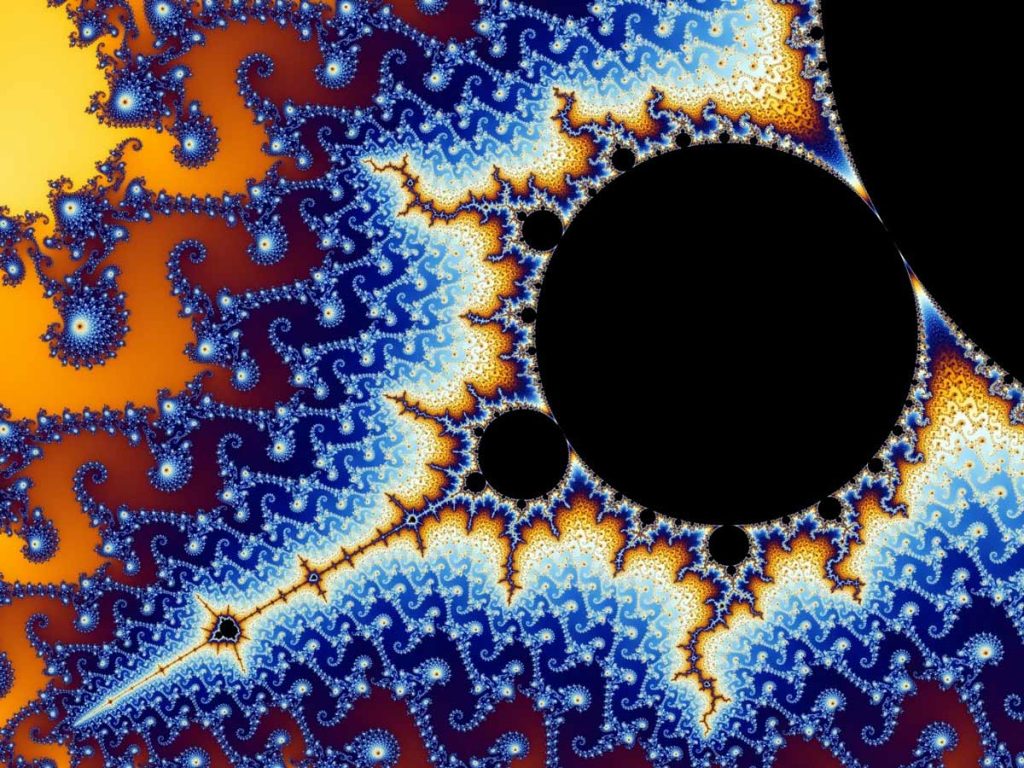

Beauty in chaos

In contrast to the Michelangelo creation image, this image is the beauty of a Mandelbrot fractal. It is a reminder of the emergence of chaos theory in maths, of how order arises out of fluctuations, of the complexity and beauty, of the patterns and connections within chaos. Keller says that “whirlwinds in meteorology are complex chaotic systems that suggest not pure chaos but rather turbulent emergence of complexity at the edge of chaos”.44

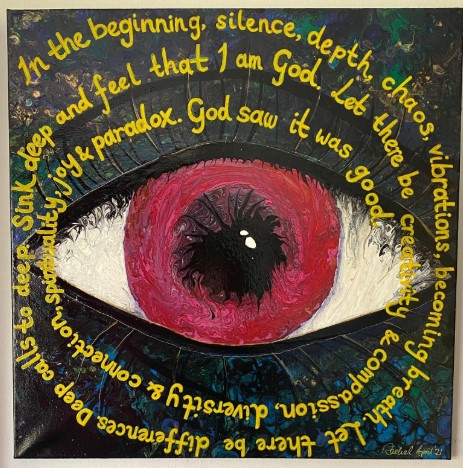

This next image is a painting I made by acrylic pouring. Colours in a cup, tipped onto canvas, colours and beauty revealed, as breath is blown over the surface of the paint.

onto canvas

This painting, making an eye, out of chaos, an eye that is a representation of God’s eye, gazing on me, on you.

It took me a long time to be able to sit with an image of God’s eye, gazing on me.

Ableism runs so deep, reinforced by so many around us. As I sat, I let God’s eye gaze on me, to see me without shame, made as I am; my response is the words written around the painting.

“In the beginning, silence, depth, chaos, vibrations, becoming breath. Let there be differences. Deep calls to deep. Sink deep and feel that I am God. Let there be creativity and compassion, diversity and connection, spirituality, joy and paradox. God saw it was good.”45 This article just tickles the surface. This raises so many questions:

- asymmetries of power, questions of control

- who gets to tell the stories, to make the meaning

- the potential for people to live without shame within our communities, for their stories to be heard, for their lives to be longer

- stigma, risk… to individuals experiencing psychosis, and to those around them

- healing

- purity

- social vs medical model of disability

- intersectionality with neurodiversity

- questions of not seeing experiencers as victims, or disordered, but perhaps as seeing them as having the luxury of spending time in the complexity on the edge of chaos, and of the depth of insight into tehom that they might bring.

I’m hoping that I’ve whet your appetite and encouraged you to consider a paradigm shift away from creating hard borders between psychosis and spirituality – that we may be willing to let God look at us, to look at each other and to allow ourselves to accept that God sees that we are good.

If you want to explore further, I encourage you to look at the “Shut In, Shut Out, Shut Up” seminars created by Fiona MacMillan with HeartEdge, which draw together different disabled and neurodivergent voices, opening up the conversation around neurodiversity, disability, ableism, faith and the church.46

About the author

Rachel Noël, known locally as the Pink Vicar, is Priest in Charge of St Mark’s Church, Pennington, a HeartEdge church in the Diocese of Winchester. Creative, colourful, enthusiastic, autistic, ADHD, bipolar and vulnerable to COVID-19, she is passionate about diversity and inclusion. Rachel leads a church that has embraced online, and is a member of the Community of Hopeweavers.

Fiona MacMillan is a disabled and neurodivergent disability advocate, practitioner, speaker and writer. She chairs the Disability Advisory Group at St Martin in the Fields, is a trustee of Inclusive Church, leads the planning team for their annual partnership conference on disability and theology, now in its 11th year, and convenes the Shut In, Shut Out, Shut Up disability seminar series on the HeartEdge platform. Fiona is a member of General Synod and of the Nazareth community.

More from this issue

Notes

1 Catherine Keller, The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming (London and New York, Routledge: 2003), 29.

2 This part of the article was first presented by Rachel Noël as a paper at the Society for the Study of Theology conference in April 2021.

3 Public Health England, “Psychosis Data Report,” September 2016, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/774680/Psychosis_data_report.pdf 5, 7.

4 https://mhfaengland.org/mhfa-centre/research-and-evaluation/mental-health-statistics/

5 Public Health England, “Psychosis Data Report,” 9.

6 Joanna Collicutt, “Jesus and Madness” in Christopher C. H. Cook and Isabelle Hamley (eds.), The Bible and Mental Health: Towards a Biblical Theology of Mental Health (SCM Press: London, 2020), 46.

7 For medical/social models, see e.g. “The Social Model of Disability,” Inclusion London, https://www.inclusionlondon.org.uk/disability-inlondon/ social-model/the-social-model-of-disability-and-the-cultural-model-of-deafness/.

8 Peter Kinderman, A Prescription for Psychiatry (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2014), 1.

9 Ibid., back cover.

10 Susan Mitchell, “Spiritual aspects of psychosis and recovery,” presented at the Royal College of Psychiatrists Annual Meeting in Edinburgh 2010, https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/members/sigs/spirituality-spsig/susan-mitchell-spiritual-aspects-of-psychosis-and-recovery-edited.pdf?sfvrsn=23c8dab0_2, 1.

11 June Boyce-Tillman, quoted by Isabel Clarke, “Psychosis and Spirituality: The Discontinuity Model” in Isabel Clarke (ed.), Psychosis and Spirituality: Consolidating the New Paradigm, 2nd ed. (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010): 103.

12 Natalie Tobert, “The Polarities of Consciousness” in Clarke (ed.), Psychosis and Spirituality, 43.

13 Richard Warner, quoted by Clarke, “Psychosis and Spirituality: The Discontinuity Model,” 111.

14 Clarke, “Psychosis and Spirituality: The Discontinuity Model,” 103.

15 Ibid., 102.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid., 104.

18 Ibid., 106.

19 Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr (London and New York: Routledge, 2002).

20 Clarke, “Psychosis and Spirituality: The Discontinuity Model,” 111.

21 Karen O’Donnell and Katie Cross (eds.), Feminist Trauma Theologies: Body, Scripture & Church in Critical Perspective (London: SCM Press, 2020).

22 Leah Smith, “#Ableism”, Center for Disability Rights, accessed 9 January 2022, https://cdrnys.org/blog/uncategorized/ableism/.

23 Further insight in stories in Jean Vanier, Bob Callaghan and John Swinton, Mental Health: The Inclusive Church Resource (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 2014), particularly by Mims Hodson’s story of bipolar and faith, and being closed down in sharing experience of psychosis and spiritual experience.

24 Keller, The Face of the Deep, 9.

25 Ibid., 17.

26 Ibid., 62.

27 Ibid., 84.

28 Jason Goroncy, “A Note on Catherine Keller’s The Face of the Deep,” jasongoroncy.com, 6 August 2014, https://jasongoroncy.com/2014/08/06/a-note-on-catherine-kellers-face-of-the-deep/.

29 This section was first put together by Fiona MacMillan and Rachel Noël for a HeartEdge “Shut In, Shut Out, Shut Up” seminar: “Shut In Shut Out Shut Up 3 2 Ableism, Faith & Church”, YouTube, 31 May 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GnwyXM2OTO4.

30 Gen. 1:27 (NRSV).

31 Gen 2:25 (NIV).

32 Brene Brown, Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience (London: Ebury Publishing: 2021), Kindle edition, location 2311.

33 Judith Rossall, Forbidden Fruit and Fig Leaves (London: SCM Press, 2020), 5.

34 Shane Clifton, “Crippling Christian Theology: Reflections of a post-Pentecostal Disability Theologian,” ABC Religion & Ethics, 5 December 2020, accessed 31 October 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/religion/crippling-christian-theology-disability-faith-and-doubt/12952958.

35 June Boyce-Tillmann, “Language” in Something Worth Sharing (Inclusive Church, 2018), accessed 31 October 2021, https://www.inclusive-church.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Something-Worth-Sharing-WEB.pdf, 15.

36 Ibid., 14.

37 Rev. 21:4 (NIV).

38 Amos Yong, The Bible, Disability, and the Church: A New Vision of the People of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011), 95. 39 2 Cor. 12:9–10 (NRSV).

40 Matt 5:3 (NRSV).

41 Acts 2:17 (NRSV).

42 Samuel Wells, Incarnational Ministry: Being with the Church (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2017).

43 Brown, Atlas of the Heart, Kindle edition, location 2528.

44 Keller, The Face of the Deep, 140.

45 Rachel Noël – “God’s Eye” painting (2021).

46 I owe personal thanks to Fiona, for her courage, persistence, perseverance and hard work in making these events happen, in educating, in supporting, in challenging the deep language that is throughout so much of church culture. Fiona has also worked with me in putting together the part of this article on ableism, helping me accept God’s Spirit at work in me, in the reality of the body and mind that I have, and that that same Spirit is also at work in you.