Anvil journal of theology and mission

When the poisonous tree attempts to produce an antidote: colonialism, colonial CMS missions and the caste system in Kerala

by Shemil Mathew

I am writing this article at a time when there is a heightened interest in race, racism and racial prejudice in the UK. There are two reasons behind this increased interest: the first is the discovery that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the black, Asian and ethnic minority communities disproportionately both in terms of infection rate and severity of the infection; second is the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted around the globe in response to the murder of George Floyd on 25 May 2020.

In many ways, these related issues also inaugurated a καιρός, Kairos, moment, reminding many of the “not so great” history of Great Britain. Questions were raised about the role of the church in the slave trade and its colonial legacy as well as the issue of present-day racism within the church. This article is being published in Anvil, a publication of Church Mission Society (CMS). As it is a mission agency started in response to the need for mission in newly “discovered” and colonised lands, it is indisputable that the history of CMS is entangled with that of British colonial expansion. The poisonous tree in my title represents the colonial establishment with its branches of political, social, economic and cultural oppression. The antidote, born out of the same tree, is the colonial missions. This article is not an attempt to find excuses for crimes of racial prejudice or exploitation of the colonial era; rather, it looks at an example of CMS missionaries who attempted, though only with marginal success, to work against the caste system of Kerala.

In a number of ways I am writing this paper very much as an insider. My ancestors were part of the ancient Church of India. There is a family tree hanging in my ancestral home proudly affirming my lineage to those Namuthiri (a caste group) families believed to have been converted by St Thomas. I am also an insider of the caste system. My school leaving certificate says my caste is “Syrian Christian” and for most of my early life I took for granted the privileges I had as a high-caste Christian. I am also an insider in terms of CMS’s legacy and its current existence as a missional community. Sometime in the nineteenth century, my great-grandfather converted from the Syrian Church to the Anglican Church through the influence of CMS missionaries. My education from pre-primary to university level was in schools established by CMS in India. Moreover, after completing my theological degree, I worked for CMS on and off for 10 years.

The physical and geographical context of this paper is the current south Indian state of Kerala. From a Christian point of view, Kerala is home to one of the oldest Christian communities in the world (dating back to 52AD with the arrival of St Thomas, the apostle); it was also a significant field for CMS missions in the nineteenth century. The central theme of this article is the complicated relationship between the racial prejudices of the colonial era and its effect on the age-old racial oppression perpetrated in the form of the caste system. I start with a short description of the caste system as we know it today, then proceed to argue that it is the result of an interplay of the existing Varna system and British enlightenment thinking in the context of ever-growing colonial/imperial exploitative ambitions and greed. Just as pseudoscientific racial categorisations and racism were used as an effective tool of oppression in justifying and perpetuating the transatlantic slave trade, caste in Kerala became a tool of oppression. I look at how the poisonous tree of colonialism also produced colonial mission movements such as CMS, which attempted to work against the caste system. I conclude that this attempt at being an antidote for the caste system was limited by its association with the poisonous tree of western colonialism and the world view associated with it.

Varna (वर्ण) system

The word “varna” means colour. As it was practised for centuries in India, the Varna system divides society into occupational categories, putting the Brahmins or the priestly class at the top with the agrarian and menial labourers and tribal people at the bottom. This system is both social and religious, with associated myths and ritual impurity ascribed to the lowest of the Varnas. Just like the Indian religions (and the nation itself) of the precolonial era, there was not a particularly consistent or organised system across the subcontinent. It operated based on the relationship between the people groups, not on one particular individual’s merit or ability. When significant social changes occurred, such as the arrival of a new group, the system shifted to assimilate the new group and assigned them a place within. Penelope Carson, in her article on the interaction of Christianity, colonialism and Hinduism, building on this flexible understanding of the Varna system, argues that in precolonial Kerala it was much more flexible than the British understood. [1] She gives two examples to illustrate this point. The first is that of the Hindu converts to Christianity and Islam; both of these groups were assigned a particular place within the system. The second is the Jewish and Christian immigrants that arrived in Kerala in the fourth century, who were also assigned a status in the system.

The development of the caste system: a relational system becomes a set of pseudoscientific race categories

The word “caste” was derived from the Portuguese word casta – meaning race or breed. The Varna system came to be referred to as the caste system in colonial times. Today the caste system is a rigid and closed matrilineal system with no allowances for social mobility. Postcolonial critiques of the caste system such as those of Nicholas Dirks and Shashi Tharoor (a member of parliament from Kerala) argue that the shift from the Varna system to the caste system is the result of interaction between the post-Enlightenment British mindset and colonial establishment’s desire for expansion and exploitation. [2, 3]

Colonialism, in its genesis and ideology, is heavily indebted to Enlightenment thinking and scientific reasoning born out of a desire for progress. The Industrial Revolution, from the perspective of those leading it, required cheap labour (resulting in the slave trade) and raw materials. In this context, scientific reasoning provided not only new avenues for profitmaking but also often moral and religious legitimacy for exploitive relationships such as slave and master and the colonialist and the colonised.

The pseudoscientific race theories that prevailed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and perhaps to this day remain in our societies) provided a clear framework for such divisions. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s race categorisation, for example, divided the people of the world into five groups: the Caucasian or white race; the Mongolian or yellow race; the Malayan or brown race; the Ethiopian or black race; the American or red race, including American Indians. [4] This formed the roots of the understanding of race in the colonial period. Blumenbach was the first to coin the word “Caucasian” and asserted the superiority of this white race over the others. His understanding of “superiority” gave Christian Europe both the motive for engaging in a mission of civilising and the confidence to colonise. At the same time, further division of the colonial subjects into categories (often opposing one another) was part of the Indian colonial administration’s “divide and rule” policy. Tharoor argues that the scientific tools of anthropology and statistical tools such a census were used not to fuse the diverse groups but to “separate, classify and divide”. [5]

A secondary reason (though it’s not an excuse) for the colonial desire to classify and divide peoples could be that Enlightenment reasoning could not understand societies and people groups who had a different way of thinking. In his book Homo Hierarchicus (1970), Louis Dumont provides a western sociological analysis of the Varna system, arguing that one of the main reasons for the misunderstanding of the caste system was that it emphasised the totality of the society, thereby making it unintelligible to the colonial West. [6]

The British colonial administration and anthropologists of the period went to great lengths to classify and categorise the castes of India. The first step towards this was translating the hitherto obscure Hindu law book The Manusmṛiti (Sanskrit: मनुस्मृति), which contained a precise classification of the Varnas as we know it today. The word “caste” was used to represent the system, making a clear shift from occupational and relational categories of the Varna system to one that is decided by birth with no possibility of mobility. The Indian Penal Code amendment of 1870 was based on the caste lines that were constructed and from that point Indian society became divided into castes. In other words, we have to agree with Tharoor when he argued that caste was another incident where “the British had defined to their own satisfaction what they construed as Indian rules and customs, then the Indians had to conform to these constructions”. [7]

The mission of help: eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial mission theology of superiority

CMS has a peculiar history in Kerala because, unlike the other places where missionaries were sent, CMS missionaries in Kerala were sent to work not with people of other faiths but with the ancient Christians of India. [8] Although earlier traders and colonialists were always followed by missionaries, both the British East India Company and its successor, the British Raj, were opposed to any missionary activity in their area. In his A History of Global Anglicanism, Kevin Ward elaborates on this anti-missionary sentiment with reference to Warren Hastings, the governor general of India between 1774 and 1784 who argued that missionary activity is “not consistent with the security of the Empire as it treats the religions established in the country with contempt”. [9] For many years, an Anglican priestly presence in India was limited to colonial army chaplains; early missionaries such as William Carey, whom I will discuss below, were denied access to land in British territory.

The theology of mission and evangelism held by CMS missionaries (and the colonial missionaries in general) was no doubt influenced by the new status of Christian nations as colonial masters. This can be seen in the case of William Carey, the Baptist missionary to India hailed as the father of the modern missionary movement: his famous pamphlet explaining the need of missions to the colonial world was entitled An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians, to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. [10] This title clearly highlights two critical characteristics of the colonial missions: firstly, the evangelisation of groups of people newly subjugated by colonial expansion was seen as a duty rather than a mere opportunity; secondly, the fulfilment of this obligation was considered the responsibility not of the conquering nations or their churches but of the individual people of these nations. This sense of personal obligation added to an already underlying individualistic theology that emphasised personal salvation held by the Anglican evangelical missionaries of CMS.

The language of obligation and burden came out of a perceived understanding of moral and religious superiority of the British missionaries and their churches. This superiority complex can be visibly identified in the records of official conversations between the ancient Church of India (known as the Syrian Church of India – a name dating back to the Portuguese colonial era, due to the affiliation to the patriarch of Syria as opposed to that of Rome) and the Church of England. One of the earliest such records is that of the Revd Claudius Buchanan, vice-provost of the College of Fort William in Calcutta, with the Metran (Metropolitan) Dionysius of the Syrian Church, facilitated by the then British Resident Colonel Munro. [11] This conversation is recorded in Buchanan’s book Christian Researches in Asia (1812) [12] and is analysed in detail by Stephen Neill. [13] Its two main themes were the translation of the Bible into the local language Malayalam and a possible union of the Indian Church with the Church of England. The Metran was happy to consider both options provided that the traditions of the Indian Church were protected. Buchanan rightly sensed the anti-Roman sentiment that existed in the Indian Syrian Church and understood it as a common factor that might unite the churches; he failed, though, to see the connection between this anti-Roman sentiment and the Syrian Church’s earlier encounters with colonial Christianity. [14] Furthermore, Buchanan didn’t comprehend that this sentiment was only a small part of the identity of the Syrian Church: the Indian Church was proud of its heritage, dating back to the days of St Thomas, as well as its unique liturgy and doctrine. Neill writes:

[Buchanan] believed himself to have discovered a primitive, and in the main pure, church which had for the most part escaped what he regarded as the deformities of the church of Rome. He gravely underestimated the differences which in fact existed between the Church of England and the Thomas Christians. [15]

The superiority complex evident in this interaction between the ancient Indian Church and the colonial Church of England, perhaps further fuelled by the British colonial establishment in India, was also present in the work of the CMS missions in Kerala. The relationship between CMS missionaries and the Syrian Church was under constant strain as the whole project was founded on the joint misconception that the Church in India was inferior to the Church of England and that it would accept the reforming steps proposed by the missionaries. [16] At the same time, the Syrian Church of India – with its nearly 2,000 years of history and previous experience of defending their traditions from the Roman missionaries – found the missionaries’ suggestions of reform offensive.

Cyril Bruce Firth, for example, says that “Mar Dionysius [then bishop of the Indian Church] was alarmed” when he heard that the first CMS missionary, Thomas Norton, was supposed to live and work from the newly constructed seminary. [17] After much discussion, it was mutually agreed that Norton should live in Alleppey (some hours away by boat) and help at the seminary occasionally. Alongside the Mission of Help, Norton (and others who followed) also started local churches of their own. [18] This gave the Syrian Church concern that CMS missionaries may cause a schism. The directive that was given to CMS missionaries until the official end of the Mission of Help in 1836 from both the London and Madras offices of CMS, was not to proselytise Syrian Christians but to work alongside them. [19]

CMS missionaries and caste – poisonous trees attempt to produce the antidote

This paper has so far demonstrated that the colonial establishment was responsible to some extent for creating the caste system as we know it today. Moreover, it has argued that the colonial mission movements stemmed from a feeling of obligation based on a sense of not just political but also racial and religious superiority. Furthermore, it has advanced the idea that the relationship between the Syrian Church and the CMS missions was set up with this superiority in mind. In short: the philosophical, scientific, political and even theological will of the era was in favour of racial classification and of prejudice based on such a classification.

Before we analyse the work of the CMS missionaries, it is necessary to accept that the history of CMS missions in Kerala is often prejudiced against the Dalit Christians. [20] Centuries of oppression and denial of access to education robbed the Dalit communities of India of their history. Just like the Indian Christian theology is predominantly a high-caste or Brahminical theology, the history of Christianity in India is also written from the perspective of high-caste Christians. Anglican churches established by CMS missionaries after the independence of India became part of the United Church of South India (CSI). Historians from CSI, such as Samuel Nellimukal in his History of Social Transformation in Kerala, consider western missionaries – particularly CMS missionaries – to have started the movement of social transformation in Kerala through their introduction of schools and colleges. [21] There is much truth in this argument, mainly because the colonial government as such had no interest in investing in education for the masses. However, it must be noted that the education – particularly the theological education – of Syrian Christians was a primary rationale behind the foundation of the Mission of Help. It is often forgotten that this specific remit of limiting educational and religious activity to Syrian churches actually prevented social transformation by denying Dalits access to education. Although there were a few exceptions before the end of the Mission of Help, access to the educational institutions created by CMS missionaries was entirely limited to Syrian Christians, with the exception of some higher-caste Hindus and Muslims.

Vinil Paul, a researcher of CMS missions in Kerala who has compared CMS with the Basel Mission (a Swiss German organisation that was operational in Kerala in the same period), has highlighted the different approaches of the two mission agencies to the caste system, even after the end of the Mission of Help and the beginning of independent CMS missions. The Basel Mission insisted that once someone became a Christian, they had to renounce their caste identity. In contrast, CMS maintained caste segregation in the churches, either by keeping separate seating areas for different castes or by establishing different churches for higher-caste and lower-caste converts. Paul, in his article on the political history of colonial Dalit education in Kerala, describes the story of the Revd Cornelius Hooton. Hooton was a Dalit convert to Christianity (from Pulaya caste): his family was baptised into Christianity in the 1850s in Cochin by CMS missionaries. Though there were many schools established in the area, children from the lower-caste backgrounds were never admitted to CMS schools as they were primarily for the Syrians. The Revd Richard Collins, the then principal of the CMS College (at that time called East Seminary), decided to admit Hooton in spite of the caste restrictions. This radical move resulted in a severe reaction from the Syrian Christians and ended up in communal violence and riot. Hooton escaped from the college with the help of CMS missionaries and took refuge with the missionaries of the Basel Mission in the northern part of Kerala. He was later ordained as a priest in the Basel Mission churches. [22] The practice of caste segregation continued in the churches established by CMS, through the end of the Mission of Help in 1836, through Indian Independence, and into the present day. It still exists in some areas of my home diocese of Central Kerala.

The Mission of Help formally came to an end with the Syrian Church’s Synod of 1836 at Mavelikara, which rejected the reforms suggested by the CMS missionaries. There is a great deal of scholarly discussion around the reason why the Mission of Help came to an end. Syrian Christian scholars such as P. Cheriyan, who analyses the missionary records, argue that the second wave of CMS missionaries – mainly the Revd Woodcock and the Revd Peet – were less tolerant towards what they considered non-scriptural practices within the Syrian Church (p. 217). [23] These practices included praying for the dead, intercession of the saints, etc. However, it also needs to be accepted that these new missionaries also challenged the practices of ritual purity. For example, Nellimukal cites an incident in 1835, at the Syrian Church of Manarkat where Joseph Peet openly challenged the notion of ritual purity. [24]

There is no question that the official breaking of ties with the Syrian Church in 1836 enabled CMS missionaries to work among the non- Christian population of Kerala in general and in particular people of lower castes. Referring to CMS proceedings, Nellimukal refers to Peet’s recollection that in his Mavelikara mission he insisted that new converts had to reject caste not just by taking off the visible caste symbols but also by eating together with the people of all castes.

The years that followed separation from the Syrian Church saw a growth in CMS activity among the Dalits and tribal communities of the eastern hills of Kerala. Henry Baker (Jr) started working among the tribal peoples in response to a request by their leaders to provide them with education. Paul, referring to his comparative study of responses to the caste system by the Basel Mission and CMS in Kerala, argues that this request to Baker came as a direct result of the visible social change tribal peoples had witnessed among the Dalit communities under the Basel Mission areas. [25]

Neill, looking at the Madras missionary conference of 1850, says that most mission agencies of the time (except for the Leipzig Evangelical Lutheran Mission) adopted a policy that “no one should be admitted to baptism until he [sic] is shown that he [sic] prepared to break caste by eating food prepared by a Paraiyan [a person of Dalit caste]”. [26] This statement affirms that in spite of widespread philosophical, social, political and even theological views of the time, which favoured racial division and segregation, the missionary world view also contained a spirit of social reform and an underlying belief in the value of all life and soul. This spirit of reform was hindered in Kerala by the alliance of CMS missions with the Syrian Church, which effectively stopped them from working with the Dalit communities.

It is apparent that the relationship between CMS missionaries in Kerala and the caste system was complicated. Nevertheless, even with its failings and limitations, it was undoubtedly a relationship that transformed the system for the better.

Conclusion

This paper, in its first part, discussed how the caste system, as we know it today, is the result of the encounter between the poisonous tree of colonialism and the Varna system. As a result, the caste system today is closed and matrilinear: the case made for the division of people resembles that of pseudoscientific race theories. The second part of this paper examined another fruit of the colonial expansion: the colonial mission movement’s attempts to work against the caste system and bring social change.

The CMS missionaries, primarily through the establishment of schools and colleges, have brought about considerable social change in Kerala. However, their relationship with the Syrian Church, rooted in their belief in the superiority of the Church of England over the ancient Church of India, and in their hope of the conversion of the Syrian Church to Anglicanism, created a major stumbling block to real social transformation.

Further reflections from the Revd Dr Anderson Jeremiah

Having written the article, I asked my PhD supervisor, Revd Dr Jeremiah, if he would be willing to offer some further reflections on it. He is from a Dalit background and has written extensively on Dalit theology and the Dalit struggle against oppression. I thought it would be helpful to see how our own backgrounds might bring different perspectives. I am grateful for his response.

In this fascinating article, Mathew identifies significant points about the links between colonialism and various mission organisations in India. Broadly speaking, Mathew captures the fraught relationship between mission organisations and colonial structures. However, with regards to caste system and colonialism in India some points need to be clarified.

Firstly, it is not only the sense of superiority of CMS missionaries, but the same sense of superiority held by the Indian Syrian Church that contributed to the complex and often mistrustful relationship between these two bodies. As it becomes apparently clear in this article, the Indian Syrian Church prides itself as the ancient church in India and to have a foreign colonial mission to come in the name of offering missional help was seen as insulting, to say the least. Such perception combined with theological and ecclesiological differences must have escalated the mistrust and bad blood between these two strands of churches and its mission in India.

Secondly, with regards to the colonial system and its relationship to the caste system, it must be clarified that they didn’t “invent” but, as is the case across various colonial processes, simply instrumentalised an existing system of prejudice and discrimination to serve the imperial ambitions. Having said that, the British colonial powers certainly built on the previous colonial exercise in systematising the Indian subcontinent for administrative purposes. Such a perspective was certainly shaped by a racialised world view prevalent in Europe that time. Therefore, it is significant to acknowledge that various mission organisations birthed in such a graded social context of Europe inherently subscribed to them.

Thirdly, the article also helpfully distinguishes between CMS and other non-British mission organisations. This distinction is an interesting one, because mission organisations carried the burden of their colonial association. In this instance, the Basel Mission didn’t have the same intimate colonial relationship as CMS did with British Empire. Therefore, some mission organisations like the Basel Mission or the American Arcot Mission of the Reformed Church in America from the United States had the freedom to engage in much more creative mission practices in India.

Fourthly, with regards to the attitude to Dalits, the article does well to highlight the lasting impact of caste-based discrimination within Indian Christianity. Mathew sheds light on the affirmative actions taken by CMS and other organisations in developing an inclusive Christian community. Further, it must be borne in mind that the missionaries, as much as they advocated the inclusion of untouchables into the Christian fold, didn’t follow a strict rule to discourage the practice of the caste system within the “high-caste” Christian converts. In other words, they turned a blind eye to the continuation of caste practice among the “highercaste” Christians, in terms of marriage, hospitality and other sociocultural practices. The result was that when Dalit Christians were included in worship, it became unacceptable to the high-caste converts. Therefore, we see several segregated places of worship from CMS background churches in Kerala.

Finally, Mathew certainly touches upon the sensitive issue of Syrian Christians in India continuing to enjoy “privileged minority status” and resisting any process that would question such a notion. What is fascinating in this analysis is how, to a large extent, Syrian Christians were also mimicking the same colonial attitude that they resisted in CMS missionaries. So, it is not simply about “colonialism” but how privilege colours Christian mission.

About the authors

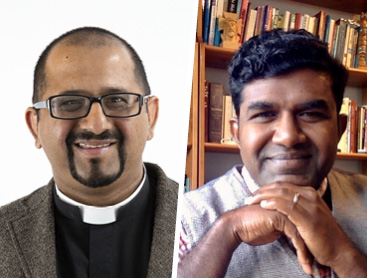

The Revd Shemil Mathew is the Anglican chaplain to Oxford Brookes University and teaches contextual theology on the CMS pioneer teaching programme and at Ripon College Cuddesdon. He and his wife Becky were mission partners with CMS. Shemil is one of the founding members of Anglican Minority Ethnic Network (AMEN) and is currently writing his PhD on diaspora Anglicans in the UK and their relationship with the Church of England.

The Revd Dr Anderson H. M. Jeremiah is lecturer in world Christianity and religious studies in the department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion at Lancaster University. He is an Anglican theologian and priest from the Church of South India (an Anglican province). He currently serves the Church of England in Lancashire, as Bishop’s Adviser on BAME Affairs in the Diocese of Blackburn.

More from this issue

Notes

[1] Penelope Carson, “Christianity, Colonialism, and Hinduism in Kerala: Integration, Adaptation, or Confrontation?“ in Christians and Missionaries in India: Cross-Cultural Communication since 1500, ed. Robert Eric Frykenberg (London: Routledge Curzon, 2003), 148.

[2] Nicholas B. Dirks, Castes of Mind : Colonialism and the Making of Modern India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001) .

[3] Shashi Tharoor, An Era of Darkness: The British Empire In India (New Delhi: Aleph Book Company, 2016).

[4] Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, The Elements of Physiology, trans. John Elliotson (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1828).

[5] Tharoor, An Era of Darkness, 123.

[6] Louis Dumont, Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and its Implications, trans. Mark Sainsbury (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1970).

[7] Tharoor, An Era of Darkness, 123.

[8] Vinil Paul, “Colonial Keralatheiay Dalitha Vidyabyasatheinti Rarstriya Charitram (A Political History of Colonial Dalit Education),” Mathrubhumi (May 2020 ), 20–25.

[9] Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[10] William Carey, An Enquiry Into the Obligations of Christians, to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens: In which the Religious State of the Different Nations of the World, the Success of Former Undertakings, and the Practicability of Further Undertakings, are Considered (Leicester: Ann Ireland, 1792).

[11] Colonel Munro was a devoted evangelical Christian and had an excellent relationship with the queen of Travancore. He was appointed as the prime minister of Travancore and has played a seminal role in the establishment and development of CMS mission work in Kerala.

[12] Claudius Buchanan, Christian Researches in Asia (New York: Richard Scott, 1812).

[13] Stephen Neill, A History of Christianity in India: 1707–1858 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 238–39.

[14] In the seventeenth century, Roman Catholic missionaries from Portugal attempted to annexe the Indian Church. This resulted in the famous declaration, known as the Kunankurishu Satyam, of the Indian Church rejecting Rome, as well as a bitter split in the church.

[15] Stephen Neill, A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 239.

[16] Considerable research has been carried out on what went wrong in the breaking of the relationship between the CMS missionaries and the Syrian Church: it all points towards the doctrinal differences between the Syrian Church and Church of England. See P. Cheriyan, The Malabar Syrians and the Church Missionary Society, 1816–1840 (Kottayam: Church Missionary Society’s Press and Book Depot, 1935).

[17] Cyril Bruce Firth, An Introduction to Indian Church History (Madras: CLS, for the Indian Theological Library of the Senate of Serampore College, 1961), 169.

[18] The new mission stations and churches that CMS established followed an Anglican liturgical and theological tradition, although services were often translated into Malayalam.

[19] C. Y. Thomas, S. Nellimukal , R. C. Ittyvaraya, M. K. Cheriyan, N. Chacko, G. Oomen, S. Thomas, Oru Preshithaprayana Charithram (Church History), ed. Samuel Nellimukal, trans. Shemil Mathew, 3 vols.; vol. 1, Oru Preshithaprayana Charithram (Church History) (Kottayam: Church of South India Madhya Kerala Diocese, 2016), 338–406.

[20] Accepting the years of oppression and the resulted brokenness of the untouchable/lowest caste of people, the Indian constitution adopted the word Dalit (meaning “broke”) to represent the entirety of the oppressed classes.

[21] Samuel Nellimukal, Keralathile Samuhyaparivarthanam (Kottayam: Kerala KS Books, 2003).

[22] Paul, “Colonial Keralatheiay Dalitha Vidyabyasatheinti Rarstriya Charitram.”

[23] P. Cheriyan, The Malabar Syrians and the Church Missionary Society, 1816–1840 (Kottayam: Church Missionary Society’s Press and Book Depot, 1935), 217.

[24] Nellimukal , Oru Preshithaprayana Charithram 1, 425.

[25] Paul, “Colonial Keralatheiay Dalitha Vidyabyasatheinti Rarstriya Charitram,” 28.

[26] Neill, A History of Christianity in India: 1707–1858, 406.