Remembering Francisco Perez: a Wichí leader’s long road to land rights

In June 2021, COVID-19 ended the life of Wichí activist leader Francisco Perez. But Perez’s legacy lives on in a hard-won land rights victory for the indigenous people of the Chaco, South America.

By Chris Wallis, mission associate

He spoke before hundreds. He met with presidents, state governors and countless parliamentary authorities. He defended his people’s land claim before the lawyers of the Interamerican Human Rights Commission in Washington DC and before judges of the Interamerican Human Rights Court in Costa Rica. He featured in newspapers, magazines and on television. But Francisco Perez was never attracted to the limelight. True to his Wichí roots, he always wanted to return home to the Chaco as quickly as possible.

In 1996 the glossy Argentine magazine Gente listed Francisco among the year’s celebrities and he was flown to Buenos Aires and accommodated in a five-star hotel. At supper, the waiter told Francisco that with the magazine paying, he could order anything he liked: champagne, caviar…. Francisco replied, “Iguana, please.” The large lizard is typical in the Chaco and considered good Wichí food. Francisco wasn’t easily impressed by the attractions of modern consumer society.

A man with a mission

He was also deeply imbued with Christian faith. After his death, Helena and I visited his widow, Liliana, and the family. Liliana recalled seeing him read his Bible and pray every evening. For me his commitment to bettering the situation of his people, in the face of many difficulties, was unmistakably his Christian witness.

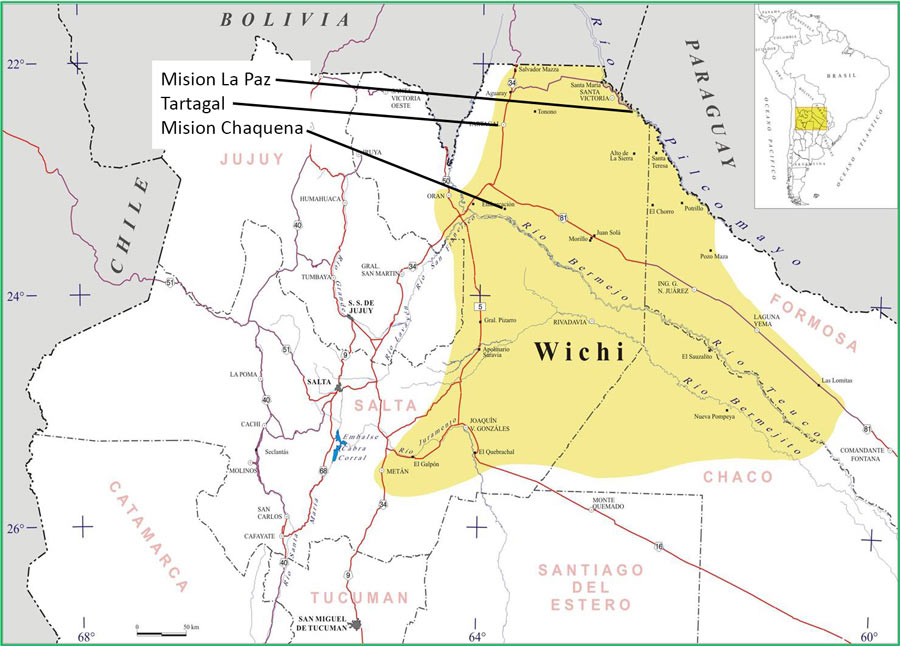

In an interview around 1994, Francisco commented that, after three years in the 1960s studying in the Anglican Mission centre Mision Chaquena (with SAMS mission partners such as Maurice Jones, Barbara Kitchin, Kevin Bewley, Pat Harris and Jeanne Carter) and another three years studying and working in Tartagal, more than 200km away from his home in Alto de la Sierra, he returned to the Pilcomayo with the following intention: “I was keen to work, to help both my own kin and also those who were not, to do whatever I could to resolve their problems. I wasn’t thinking of working inside the church as a pastor, but independently alongside the church.”

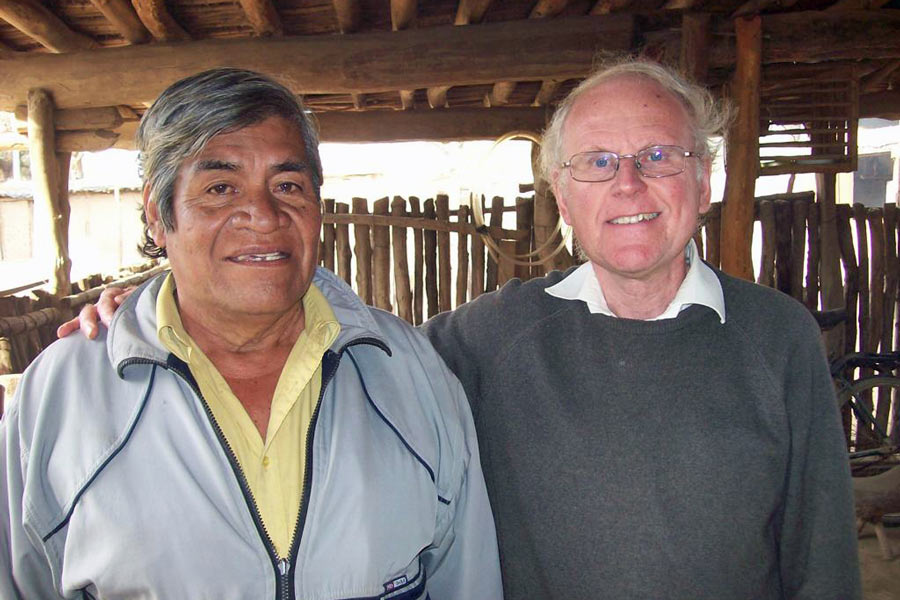

I first met Francisco in 1979. He was living in Mision La Paz, on the Pilcomayo river, and working as a technical assistant for the Anglican Agricultural Development Programme, Iniciativa Cristiana. He travelled extensively, visiting Wichí and Chorote communities to support small agricultural and handicraft projects. He frequently made trips through dust or mud to take patients to the hospital in Tartagal, some 180 km away.

Bob Lunt, a linguist, had just arrived in La Paz to supervise the translation of the entire Bible into the Wichí language, a monumental task completed in 2002. Bob recalls that despite a heavy workload, every Saturday afternoon Francisco would meet with him, answer his questions and provide further instruction. Bob says Francisco “opened the door so that I could really learn the Wichí language”. Francisco’s dedication to his people’s language continued throughout his life. He was a founding and active member of the Wichí Language Council.

When I next met Francisco in 1990, his experience of dealing with white society had greatly expanded. He was elected onto the municipal council for two years and then appointed assistant environmental inspector, responsible for controlling logging in the area that was legally still all state land.

It was during this period that Francisco embarked on what I believe was his God-given mission: to gain recognition for his people’s right to claim legal possession of the lands of their ancestors.

After the return of democracy in Argentina in 1983 there were moves by the Salta provincial government to divide and sell off the State Lands (Lotes Fiscales) Nos. 55 and 14 (some 640,000 hectares). This is the territory of the Wichí and Chorote communities near the Pilcomayo River in Salta – Francisco’s homeland.

The long fight for land rights

The government wanted to move the indigenous people into small semi-urban plots of land, provide them with a few basic services and hand these ancestral lands over to cattle ranchers. Francisco recounted how government officials met with hand-picked Wichí community leaders, bamboozling them with a splendid barbecue and special offers to get their rubber stamp for the proposal.

Recognising the danger for his people, Francisco began visiting communities, seeking support for a counter-proposal. Interestingly, he first sought out the indigenous leaders of the Anglican Church, since he suspected that political leaders had sold out to the government. With the help of a local friend he composed a declaration which was signed by representatives of 15 communities and presented to the government in June 1984. This first formal petition emphasised the need for indigenous communities to retain their territory since the people’s way of life depended on the natural resources of the forest and river.

This initial land claim formed the basis for all future claims. In 1991, under Francisco’s leadership, a much more detailed claim was presented to the provincial government, in which the communities living in the State Lands No. 55 requested a single collective title to all the lands they occupied. Subsequently, other communities in the State Lands No. 14 adhered to the land claim, extending the total area included and the number of communities involved. The 1991 proposal was prepared with the backing of the Anglican Church and the technical support of a small team, including me and my wife. From this point onwards, support for the land claim was constantly provided by the social programme of the Anglican Church (as from 1994 called ASocIANA), which has included CMS mission partners such as Andrew Leake, Nick Drayson and myself.

Up until the final favourable judgement of the Interamerican Human Rights Court (IHRC), on 6 February 2020, Francisco never allowed himself to be diverted from the goal of a single territory under a single title for all the communities. He persevered despite threats and attempts to dissuade him with tempting offers.

Francisco always looked for peaceful means to come to an agreement. The Gordian knot in reaching a solution with respect to legal possession of the land was, and still is, the presence since the beginning of the last century of criollo (non-indigenous) settlers, whose cattle roam freely across all the lands occupied by the indigenous communities. Francisco was always clear that a solution for his communities also necessarily meant a solution for the criollos, but he maintained that their own lands needed to be free of criollos and their animals. At a conference in Germany in 1996, he explained: “We don’t want to be at odds with the criollos, we don’t want to come to blows with them. No. In our claim for the land it’s not that we say that they don’t also need land. We don’t suggest that they have no right to the land, and that all the rights are on our side. This is not our idea. We maintain that they also need land, but for the peace of our communities their lands need to be separated from ours. Then they also will be at peace to develop their own way of life”.

Re-grouping with rivals

Around the year 2000, it became apparent that a major shift in the land claim strategy was necessary. Up until that time the indigenous organisation Lhaka Honhat, of which Francisco was the general coordinator, had campaigned exclusively for the recognition of indigenous rights, with the objective that the government should first delimit the lands of the indigenous communities and then allocate individual plots of land for the criollo families in the adjoining area. However, since the government had failed to take any steps in this direction, using the apparent conflict between the two groups as an excuse for inaction, a new approach was considered. With the aid of another trustworthy NGO working alongside the criollo families, it was proposed that Lhaka Honhat work towards achieving joint agreements with a criollo organisation regarding the distribution of the two State Lands – presenting the government with a united front.

This meant working with the people who were perceived by the Wichí as the root of the conflict. It was by no means an easy shift for Francisco and he had to convince the rest of the indigenous leadership of Lhaka Honhat to go along with this change. Some were clearly not happy about having to deal with the criollos. There was always an undercurrent of suspicion that the criollos would cheat them.

And so from 2001 onwards, with the accompaniment of ASocIANA and the legal advice and backing of CELS, a human rights organisation based in Buenos Aires, for nearly 20 years Francisco led a gruelling process of countless and often very tense meetings: with criollos on the one hand and lengthy and tedious meetings with government officials on the other. He also had to repeatedly present and defend the indigenous people’s claim before members of the Interamerican Human Rights Commission and finally the Court itself.

Francisco lived to see the legal battle won in 2020, but challenges remain. There are some 280 criollo families, along with their animals, that need to be relocated outside the indigenous communities’ lands and until the location of their respective plots is clearly defined it is impossible to conclude the delimitation of the whole indigenous territory. The Wichí people are often frustrated by the long drawn-out process. Understandably they want to know exactly what is and isn’t their land.

Land too late?

Beyond land distribution, there are other difficulties to navigate. Much has changed since Francisco embarked on defending his people’s land rights. When I recall early gatherings in the 1990s, I see the people sitting on the ground under the Algarrobo trees and I hear one speaker after another insisting that they depended on both the forest and the river, the forest for the honey, wild fruits and animals they hunted, the river for their fish. Francisco would say, “Maybe a few of you will one day get a government job as a health worker or an assistant teacher in the primary school, but what will the rest of you live off? We need the land, because it is the land of our ancestors, of our people’s history, and it provides us all that we need for our living.”

Back in 1984, only a handful of Wichí had completed primary education and none had finished secondary education. Today there are hundreds of Wichí attending secondary schools in the Pilcomayo area. Nearly all families receive monthly subsidies from the state, and many now live in government-built housing, with television, a freezer and other furnishings. Outside you will probably see a motorbike and its owner is likely to have a mobile phone. Consumer society has made huge inroads into the traditional Wichí way of life and children leaving school today don’t have the same expectations their parents had or the same attachment to the lands of their grandparents.

Presuming that the process of distributing and titling the land will eventually be completed – the IHRC has given the state six years to finish the process – what will the younger generation do with the almost 400,000 hectares that will belong to all the indigenous communities? How will they make use of the natural resources? Will the valuable wood be sold to outside speculators? How will the different communities decide these things together? Will they continue to abandon the ways of their forebears for the lure of convenience?

Before he died from coronavirus in the Tartagal hospital on 6 June 2021, I know these changes were on Francisco’s mind and he hoped the church would guide Wichí families in this generational crisis. Many of us continue to share his concerns.