Entangled histories: John Chilembwe

Entangled histories: John Chilembwe

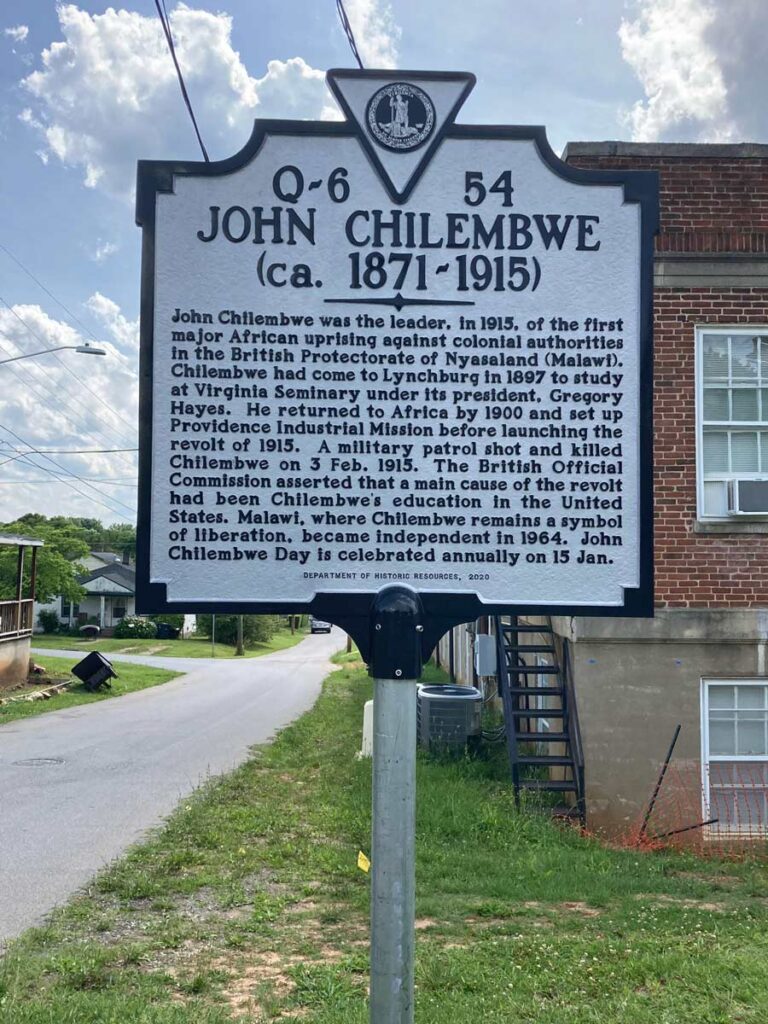

Photo: ‘Antelope’, sculpture featuring John Chilembwe by Samson Kambalu on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalger Square (© Philip Halling (cc-by-sa/2.0))

Harvey Kwiyani tells the story of a legendary figure in the resistance of colonialism, who had had a multi-faceted impact on Malawi and beyond, and whose statue now stands on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square.

by Harvey Kwiyani

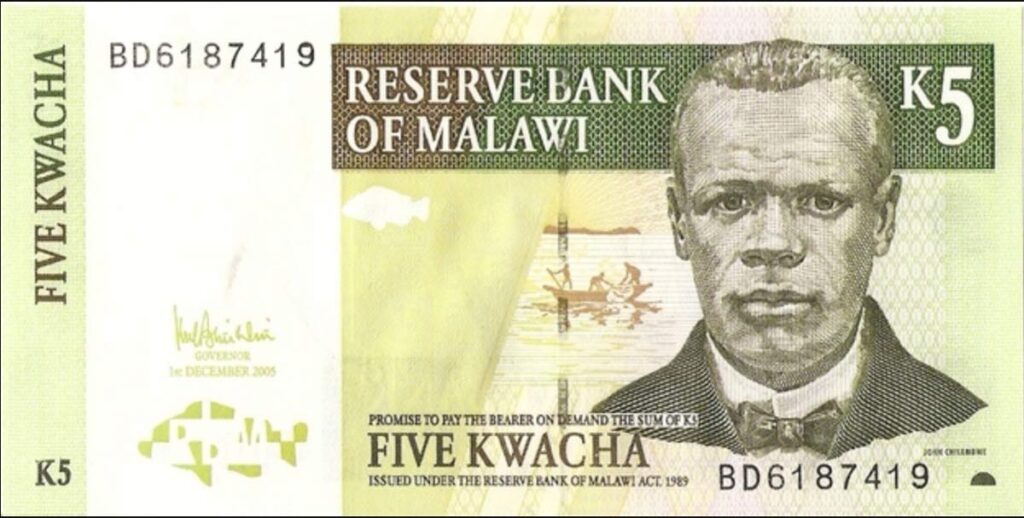

John Chilembwe is a legendary figure in Malawi. He was the subject of a conference earlier this year in Cambridge, and is the subject of Samson Kambalu’s sculpture Antelope (the meaning of Chilembwe) which is the current occupant of the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square.

Who was John Chilembwe?

Born in 1871 of Yao heritage, in 1892 Chilembwe became a servant of Joseph Booth, a British Baptist missionary from Derby who had just come to Malawi (via New Zealand and Australia).

That year Booth set up what he called the Zambezi Industrial Mission, right at the beginning of the British colonisation of the piece of land that they later called Nyasaland (and became Malawi after independence in 1964).

These first years of the process of colonisation usually entailed what was called the pacification of the people of the land – the elimination of all who would resist colonial subjugation. Malawi was no different.

A rebellious missionary

Booth came to Malawi when the pacification was just beginning and he immediately took the side of the Africans. In 1897, he published his manifesto, entitled “Africa for the Africans,” in which he pleaded with the British Crown to cede all African land back to Africans and to treat them as equals.

Of course, he was declared an enemy of the colonial enterprise and was deported by the British from Malawi in 1900. They kept deporting him from the other places he went to: by the time he came back to England in 1915, he had been deported by the British government more than five times (from different parts of South Africa and Botswana).

In 1897, Booth brought Chilembwe to Virginia in the United States, where he trained for the ministry until 1900.

Mission pioneers

When he returned to Malawi, having been ordained a Baptist pastor and established relationships with some African American leaders who would support his ministry for a long time, Chilembwe immediately established his own mission station. The Providence Industrial Mission, at Mbombwe Hill, was based just a few miles south over the Chiradzulu Hill from where my own great-great-grandfather, Mr Nacho, led the Chiradzulu Mission (a station of the Blantyre Mission that had been set up by the Church of Scotland).

All this was happening just a few more miles from Magomero, which had become the first British mission station in the region in 1861, when David Livingstone made it the homebase of the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa.

Colonial terror

By 1892, when Joseph Booth came to Malawi, David Livingstone’s daughter, Agnes, and her husband, Alexander Low Bruce (who never visited the country), had just purchased a huge piece of land at the old mission station at Magomero. Agnes put a cousin, William J Livingstone, in charge of what they named the AL Bruce Estates.

For most of his time at Magomero, William did not allow schools and churches on or close to the farm – educated Africans would be difficult to control. He also took full advantage of the colonial government’s tactics to force local people around the estate to provide him with free labour (for one week in each month).

Naturally, locals found William Livingstone quite difficult to live with.

Together with Agnes’ son, Alexander Livingstone Bruce (who came to Malawi in 1908), William unleashed terror onto the neighbours, often using physical violence to force people to work on the estate and burning down any schools and churches that emerged around the estate.

To strike a blow and die

As a result, fed up especially of the humiliation connected to the pacification of Malawi and incensed about the conscription of many young Malawians to fight against the Germans in Tanzania (which was German East Africa at the time), Chilembwe and others decided to rise up against the British colonial government and its settler farmers saying, “We need to strike a blow and die, maybe this time our blood will amount to something.”

William Livingstone at Magomero was an archenemy and special target. He was killed on 23 January 1915.

Chilembwe himself was killed on 3 February as the British government jailed and killed many Malawians in an effort to quell the uprising. The colonial government deported many Western missionaries who could, even remotely, be connected to Chilembwe.

A new law was established that required all churches registered in Malawi to have a white leader. This law was still in place in 1964 when Malawi gained its independence from Britain.

All in all, when it comes to the history of mission and Christianity in Malawi, a history dominated by names of Western missionaries, Chilembwe stands as a legendary figure. His story is not only of the church and mission but also a local Christian leader’s struggle for freedom in the context of colonialism.

The role played by the British colonial government and the Livingstones shows exactly how mission and colonialism worked hand in hand. It is for stories like these that we believe that it is time to decolonise mission.

Dr Harvey Kwiyani leads the African Christianity programme at CMS Pioneer Mission Training as wells as the Acts 11 Project, a new centre for global witness and human migration.